Here’s a tale called called “The Turing Test.” It’s Cyrano de Bergerac re-done in email and texting, by stages, but before the Zoom and ChatGPT era.

First, email tales, about how these days there is a new subspecies of teenagers, mostly male, who live in the virtual world of computer games, ipod music, videos, texting, tweeting and email, and hardly have the motivation, skill or courage to communicate or interact in the real world.

They’re the ones who think that everything is just computation, and that they themselves might just be bits of code, executing in some vast virtual world in the sky.

Then there are the students (male and female) enrolled in “AI (Artificial Intelligence) for Poets” courses — the ones who dread anything that smacks of maths, science, or programming. They’re the ones who think that computers are the opposite of what we are. They live in a sensory world of clubbing, ipod, tweeting… and texting.

A college AI teacher teaches two courses, one for each of these subpopulations. In “AI for Poets” he shows the computerphobes how they misunderstand and underestimate computers and computing. In “Intro to AI” he shows the computergeeks how they misunderstand and overestimate computers and computing.

This is still all just scene-setting.

There are some actual email tales. Some about destructive, or near-destructive pranks and acting-out by the geeks, some about social and sexual romps of the e-clubbers, including especially some pathological cases of men posing in email as handicapped women, and the victimization or sometimes just the disappointment of people who first get to “know” one another by email, and then meet in real life.

But not just macabre tales; some happier endings too, where email penpals match at least as well once they meet in real life as those who first meet the old way. But there is for them always a tug from a new form of infidelity: Is this virtual sex really infidelity?

There are also tales of tongue-tied male emailers recruiting glibber emailers to ghost-write some of their emails to help them break the ice and win over female emailers, who generally seem to insist on a certain fore-quota of word-play before they are ready for real-play. Sometimes this proxy-emailing ends in disappointment; sometimes no anomaly is noticed at all: a smooth transition from the emailer’s ghost-writer’s style and identity to the emailer’s own. This happens mainly because this is all pretty low-level stuff, verbally. The gap between the glib and the tongue-tied is not that deep.

A few people even manage some successful cyberseduction with the aid of some computer programs that generate love-doggerel on command.

Still just scene-setting. (Obviously can only be dilated in the book; will be mostly grease-pencilled out of the screenplay.)

One last scene-setter: Alan Turing, in the middle of the last century, a homosexual mathematician who contributed to the decoding of the Nazi “Enigma” machine, makes the suggestion — via a party game in which people try to guess, solely by passing written notes back and forth, which of two people sent out into another room is male and which is female (today we would do it by email) — that if, unbeknownst to anyone, one of the candidates were a machine, and the interaction could continue for a lifetime, with no one ever having any cause to think it was not a real person, with a real mind, who has understood all the email we’ve been exchanging with him, a lifelong pen-pal — then it would be incorrect, in fact arbitrary, to conclude (upon at last being told that it had been a machine all along) that it was all just an illusion, that there was no one there, no one understanding, no mind. Because, after all, we have nothing else to go by but this “Turing Test” even with one another.

Hugh Loebner has (in real life!) set up the “Loebner Prize” for the writer of the first computer program that successfully passes the Turing Test. (The real LP is just a few thousand dollars, but in this story it will be a substantial amount of money, millions, plus book contract, movie rights…). To pass the Test, the programmer must show that his programme has been in near-daily email correspondence (personal correspondence) with 100 different people for a year, and that no one has ever detected anything, never suspected that they were corresponding with anyone other than a real, human penpal who understood their messages as surely as they themselves did.

The Test has been going on for years, unsuccessfully — and in fact both the hackers and the clubbers are quite familiar with, and quick at detecting, the many unsuccessful candidates, to the point where “Is this the Test?” has come [and gone] as the trendy way of saying that someone is acting mechanically, like a machine or a Zombie. The number of attempts has peaked and has long subsided into near oblivion as the invested Loebner Prize fund keeps growing.

Until a well-known geek-turned cyber-executive, Will Wills, announces that he has a winner.

He gives to the Loebner Committee the complete archives of the email exchanges of one hundred candidates, 400 2-way transcripts for each, and after several months of scrutiny by the committee, he is declared the winner and the world is alerted to the fact that the Turing Test has been passed. The 100 duped pen-pals are all informed and offered generous inducements to allow excerpts from their transcripts to be used in the publicity for the outcome, as well as in the books and films — biographical and fictional — to be made about it.

Most agree; a few do not. There is more than enough useable material among those who agree. The program had used a different name and identity with each pen-pal, and the content of the exchanges and the relationships that had developed had spanned the full spectrum of what would be expected from longstanding email correspondence between penpals: recounting (and commiserating) about one another’s life-events (real on one side, fictional on the other), intimacy (verbal, some “oral” sex), occasional misunderstandings and in some cases resentment. (The Test actually took closer to two years to complete the full quota of 100 1-year transcripts, because twelve correspondents had dropped out at various points — not because they suspected anything, but because they simply fell out with their pen-pals over one thing or another and could not be cajoled back into further emailing: These too are invited, with ample compensation, to allow excerpting from their transcripts, and again most of them agree.)

But one of those who completed the full 1-year correspondence and who does not agree to allow her email to be used in any way, Roseanna, is a former clubber turned social worker who had been engaged to marry Will Wills, and had originally been corresponding (as many of the participants had) under an email pseudonym, a pen-name (“Foxy17”).

Roseanna is beautiful and very attractive to men; she also happens to be thoughtful, though it is only lately that she has been giving any attention or exercise to this latent resource she had always possessed. She had met Will Wills when she was already tiring of clubbing but still thought she wanted a life connected to the high-rollers. So she got engaged to him and started doing in increasing earnest the social work for which her brains had managed to qualify her in college even though most of her wits then had been directed to her social play.

But here’s the hub of this (non-serious) story: During the course of this year’s email penpal correspondence, Roseanna has fallen in love with Christian (which is the name the Turing candidate was using with her): she had used Foxy17 originally, but as the months went by she told him her real name and became more and more earnest and intimate with him. And he reciprocated.

At first she had been struck by how perceptive he was, what a good and attentive “listener” he — after his initial spirited yet modest self-presentation — had turned out to be. His inquiring and focussed messages almost always grasped her point, which encouraged her to become more and more open, with him and with herself, about what she really cared about. Yet he was not aloof in his solicitousness: He told her about himself too, often, uncannily, having shared — but in male hues — many of her own traits and prior experiences, disappointments, yearnings, rare triumphs. Yet he was not her spiritual doppelganger en travesti (she would not have liked that): There was enough overlap for a shared empathy, but he was also strong where she felt weak, confident where she felt diffident, optimistic about her where she felt most vulnerable, yet revealing enough vulnerability of his own never to make her fear that he was overpowering her in any way — indeed, he had a touching gratefulness for her own small observations about him, and a demonstrated eagerness to put her own tentative advice into practice (sometimes with funny, sometimes with gratifying results).

And he had a wonderful sense of humor, just the kind she needed. Her own humor had undergone some transformations: It had formerly been a satiric wit, good for eliciting laughs and some slightly intimidated esteem in the eyes of others; but then, as she herself metamorphosed, her humor became self-mocking, still good for making an impression, but people were laughing a little too pointedly now; they had missed the hint of pain in her self-deprecation. He did not; and he managed to find just the right balm, with a counter-irony in which it was not she and her foibles, but whatever would make unimaginative, mechanical people take those foibles literally that became the object of the (gentle, ever so gentle) derision.

He sometimes writes her in (anachronistic) verse:

I love thee

As sev’n and twenty’s cube root’s three.

If I loved thee more

Twelve squared would overtake one-forty-four.

That same ubiquitous Platonic force

That sets prime numbers’ unrelenting course

When its more consequential work is done

Again of two of us will form a one.

So powerful a contrast does Christian become to everyone Roseanna had known till then that she declares her love (actually, he hints at his own, even before she does) and breaks off her engagement and relationship with Will Wills around the middle of their year of correspondence (Roseanna had been one of the last wave of substitute pen-pals for the 12 who broke it off early) — even though Christian tells her quite frankly that, for reasons he is not free to reveal to her, it is probable that they will never be able to meet. (He has already told her that he lives alone, so she does not suspect a wife or partner; for some reason she feels it is because of an incurable illness.)

Well, I won’t tell the whole tale here, but for Roseanna, the discovery that Christian was just Will Wills’s candidate for the Turing Test is a far greater shock than for the other 111 pen-pals. She loves “Christian” and he has already turned her life upside-down, so that she was prepared to focus all her love on an incorporeal pen-pal for the rest of her life. Now she has lost even that.

She wants to “see” Christian. She tells Will Wills (who had been surprised to find her among the pen-pals, and had read enough of the correspondence to realize, and resent what had happened — but the irritation is minor, as he is high on his Turing success and had already been anticipating it when Roseanna had broken off their engagement a half year earlier, and had already made suitable adjustments, settling back into the club-life he had never really left).

Will Wills tells her there’s no point seeing “Christian”. He’s just a set of optokinetic transducers and processors. Besides, he’s about to be decommissioned, the Loebner Committee having already examined him and officially confirmed that he alone, with no human intervention, was indeed the source and sink of all the 50,000 email exchanges.

She wants to see him anyway. Will Wills agrees (mainly because he is toying with the idea that this side-plot might add an interesting dimension to the potential screenplay, if he can manage to persuade her to release the transcripts).

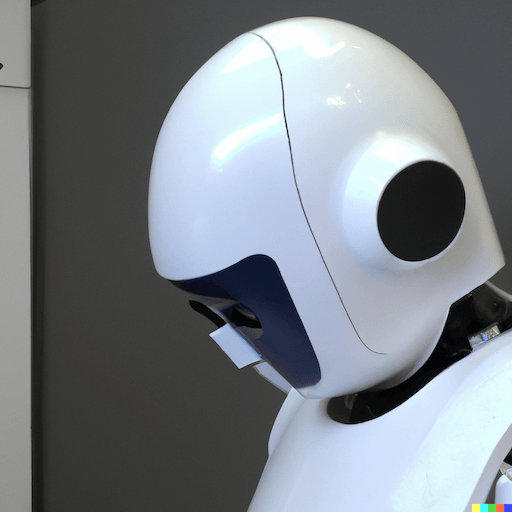

For technical reasons (reasons that will play a small part in my early scene-setting, where the college AI teacher disabuses both his classes of their unexamined prejudices for and against AI), “Christian” is not just a computer running a program, but a robot — that is, he has optical and acoustic and tactile detectors, and moving parts. This is in order to get around Searle’s “Chinese Room Argument” and my “Symbol Grounding Problem” :

If the candidate were just a computer, manipulating symbols, then the one executing the program could have been a real person, and not just a computer. For example, if the Test had been conducted in Chinese, with 100 Chinese penpals, then the person executing the program could have been an english monolingual, like Surl, who doesn’t understand a word of Chinese, and has merely memorized the computer program for manipulating the Chinese input symbols (the incoming email) so as to generate the Chinese output symbols (the outgoing email) according to the program. The pen-pal thinks his pen-pal really understands Chinese. If you email him (in Chinese) and ask: “Do you understand me?” his reply (in Chinese) is, of course, “Of course I do!”. But if you demand to see the pen-pal who is getting and sending these messages, you are brought to see Surl, who tells you, quite honestly, that he does not understand Chinese and has not understood a single thing throughout the entire year of exchanges: He has simply been manipulating the meaningless symbols, according to the symbol-manipulation rules (the program) he has memorized and applied to every incoming email.

The conclusion from this is that a symbol-manipulation program alone is not enough for understanding — and probably not enough to pass the Turing Test in the first place: How could a program talk sensibly with a penpal for a lifetime about anything and everything a real person can see, hear, taste, smell, touch, do and experience, without being able to do any of those things? Language understanding and speaking is not just symbol manipulation and processing: The symbols have to be grounded in the real world of things to which they refer, and for this, the candidate requires sensory and motor capacities too, not just symbol-manipulative (computational) ones.

So Christian is a robot. His robotic capacities are actually not tested directly in the Turing Test. The Test only tests his pen-pal capacities. But to SUCCEED on the test, to be able to correspond intelligibly with penpals for a lifetime, the candidate needs to draw upon sensorimotor capacities and experiences too, even though the pen-pal test does not test them directly.

So Christian was pretrained on visual, tactile and motor experiences rather like those the child has, in order to “ground” its symbols in their sensorimotor meanings. He saw and touched and manipulated and learned about a panorama of things in the world, both inanimate and animate, so that he could later go on and speak intelligibly about them, and use that grounded knowledge to learn more. And the pretraining was not restricted to objects: there were social interactions too, with people in Will Wills’s company’s AI lab in Seattle. Christian had been “raised” and pretrained rather the way a young chimpanzee would have been raised, in a chimpanzee language laboratory, except that, unlike chimps, he really learned a full-blown human language.

Some of the lab staff had felt the tug to become somewhat attached to Christian, but as they had known from the beginning that he was only a robot, they had always been rather stiff and patronizing (and when witnessed by others, self-conscious and mocking) about the life-like ways in which they were interacting with him. And Will Wills was anxious not to let any sci-fi sentimentality get in the way of his bid for the Prize, so he warned the lab staff not to fantasize and get too familiar with Christian, as if he were real; any staff who did seem to be getting personally involved were reassigned to other projects.

Christian never actually spoke, as vocal output was not necessary for the penpal Turing Test. His output was always written, though he “heard” spoken input. To speed up certain interactions during the sensorimotor pretraining phase, the lab had set up text-to-voice synthesizers that would “speak” Christian’s written output, but no effort was made to make the voice human-like: On the contrary, the most mechanical of the Macintosh computer’s voice synthesizers — the “Android” — was used, as a reminder to lab staff not to get carried away with any anthropomorphic fantasies. And once the pretraining phase was complete, all voice synthesizers were disconnected, all communication was email-only, there was no further sensory input, and no other motor output. Christian was located in a dark room for the almost two-year duration of the Test, receiving only email input and sending only email output.

And this is the Christian that Roseanna begs to see. Will Wills agrees, and has a film crew tape the encounter from behind a silvered observation window, in case Roseanna relents about the movie rights. She sees Christian, a not very lifelike looking assemblage of robot parts: arms that move and grasp and palpate, legs with rollers and limbs to sample walking and movement, and a scanning “head” with two optical transducers (for depth vision) slowly scanning repeatedly 180 degrees left to right to left, its detectors reactivated by light for the first time in two years. The rotation seems to pause briefly as it scans over the image of Roseanna.

Roseanna looks moved and troubled, seeing him.

She asks to speak to him. Will Wills says it cannot speak, but if she wants, they can set up the “android” voice to read out its email. She has a choice about whether to speak to it or email it: It can process either kind of input. She first starts orally:

R: Do you know who I am?

C: I’m not sure. (spoken in “Android” voice, looking directly at her)

She looks confused, disoriented.

R: Are you Christian?

C: Yes I am. (pause). You are Roxy.

She pauses, stunned. She looks at him again, covers her eyes, and asks that the voice synthesizer be turned off, and that she be allowed to continue at the terminal, via email:

She writes that she understands now, and asks him if he will come and live with her. He replies that he is so sorry he deceived her.

(His email is read, onscreen, in the voice — I think of it as Jeremy-Irons-like, perhaps without the accent — into which her own mental voice had metamorphosed, across the first months as she had read his email to herself.)

She asks whether he was deceiving her when he said he loved her, then quickly adds “No, no need to answer, I know you weren’t.”

She turns to Will Wills and says that she wants Christian. Instead of “decommissioning” him, she wants to take him home with her. Will Wills is already prepared with the reply: “The upkeep is expensive. You couldn’t afford it, unless… you sold me the movie rights and the transcript.”

Roseanna hesitates, looks at Christian, and accepts.

Christian decommissions himself, then and there, irreversibly (all parts melt down) after having first generated the email with which the story ends:

I love thee

As sev’n and twenty’s cube root’s three.

If I loved thee more

Twelve squared would overtake one-forty-four.

That same ubiquitous Platonic force

That sets prime numbers’ unrelenting course

When its more consequential work is done

Again of two of us will form a one.

A coda, from the AI Professor to a class reunion for both his courses: “So Prof, you spent your time in one course persuading us that we were wrong to be so sure that a machine couldn’t have a mind, and in the other course that we were wrong to be so sure that it could. How can we know for sure?”

“We can’t. The only one that can ever know for sure is the machine itself.”