SH: First, let’s set up a local context for this chat.

Could you please tell me what you know about the following topics:

1. Symbol Grounding

2. Category-learning

3. Categorical perception

4. Language Origins and Evolution

5. Minimal Grounding Sets (Minimal Feedback Vertex States of Dictionary Graphs)

ChatGPT: Certainly, let’s go over these topics one by one:

Symbol Grounding: This refers to the concept of how words (symbols) get their meanings. Harnad introduced the term in the paper “The Symbol Grounding Problem,” in which he argues that symbols’ meanings are grounded in sensory experience. For example, the word “apple” has meaning because it’s linked to our sensory experiences of seeing, touching, and tasting apples.

Category-learning: This relates to the process by which we learn to classify objects, experiences, or concepts into different categories. Harnad and his colleagues have conducted extensive research on this topic, particularly in the context of how human and artificial systems can learn to categorize. It relates closely to symbol grounding as categorization allows for the meaningful grouping of experiences which can then be symbolized.

Categorical Perception (CP): This term refers to the phenomenon where the categories possessed by a perceiver influence the perception of stimuli. For instance, humans perceive colors as distinct categories (like blue or green), even though color exists as a continuous spectrum. Harnad has extensively studied this phenomenon as a crucial component of symbol grounding and categorization.

Language Origins and Evolution: Harnad has shown interest in the origins and evolution of language as it relates to symbol grounding. The argument is that language evolved as a system of symbols grounded in sensory experience. Language’s capacity to refer to things not immediately present (displacement) and to produce an infinite number of sentences from a finite set of elements (generativity) are key points of investigation.

Minimal Grounding Sets (Minimal Feedback Vertex Sets of Dictionary Graphs): This concept is related to Harnad’s work on symbol grounding and category learning. A grounding set can be considered as the smallest set of symbols necessary to ground the meaning of other symbols in a system, ensuring there is no circularity of definitions. The feedback vertex set is a concept from graph theory, used here as a metaphor in understanding how symbols and meanings interconnect. Harnad uses this concept to further illustrate and investigate the nature of symbol grounding.

Let me know if you would like more detailed explanations or if you want to explore any other related subjects.

SH: Corrections:

Symbol Grounding is not “association” (which, in itself, means nothing but pairing). There are content words and function words. Grounding is a connection between a content word and its referent in the world. The grounding can be direct, through the speaker’s (learned) sensorimotor capacity to recognize and do the right thing with the referent (eat an “apple,” throw a “baseball”). Or the grounding can be indirect – learned verbally, by description or definition. This is for a hearer to be told by a speaker (who knows the referent of the word that the hearer does not yet know) what are the features of a word’s referent that distinguish it from the referents of other words. The referents of the words referring to the referent’s features need to already have been grounded for the hearer previously (directly or indirectly) for the hearer to be able to learn the referent of the word being defined by the speaker. The “symbol grounding problem” is that indirect verbal grounding cannot be indirect “all the way down”: it eventually has to be based on direct grounding,

Category-learning is not (just, or primarily) “grouping.” It is learning the distinguishing features of the members of the category. Except for proper names, all content words refer to categories, which need to be distinguished from the members of other categories with which they could be confused so that the categorizer can do the right thing with the members (eat an “apple,” throw a “baseball”) and not the non-members. Categorizing is the capacity to do things with the category’s members. Naming or grouping them are two of the things that can be done with the members, but eating or throwing them are others (and more important). (Nonhuman animals cannot talk, but they can learn categories and categorize too).

Categorical Perception (CP) is most important when it is learned. Category learning is learning the features that distinguish members of a category from members of other categories. The sensorimotor features can be learned directly by unsupervised exposure and supervised (reinforced) trial and error with corrective feedback from the consequences of doing the right or wrong thing.

Language Origins and Evolution: Languages consist of content and function words, syntactic rules, and sentences (propositions) with subjects and predicates and truth-values. The content words need to be grounded (directly or indirectly).

A Minimal Grounding Sets (MGS) is the smallest number of words in a dictionary that already need to be grounded such that all the rest of the words in the dictionary can be learned from definitions (propositions) composed only of one MGS’s words, or from words that can be defined from words definable from that MGS.

A “dictionary” is defined as a set of words all of which are defined in the dictionary.

The MGS is not a metaphor, nor is the minimal feedback vertex set of an oriented graph of a dictionary with edges from defining words to defined words.

ChatGPT: Thanks for the clarification and corrections. Let me restate the concepts in line with your input:

Symbol Grounding: Symbol grounding is about creating connections between content words and their referents in the world, as opposed to just “associating”. Grounding can be either direct or indirect. Direct grounding involves a speaker’s learned sensorimotor capacity to identify and interact correctly with the referent (like eating an “apple”, or throwing a “baseball”). Indirect grounding occurs when a hearer learns the referent of a word verbally, through description or definition, from a speaker who is already familiar with that referent. However, it’s important to note that indirect grounding cannot function in isolation; it eventually needs to be based on direct grounding.

Category-learning: Category-learning is more about learning the distinguishing features of the members of a category than just grouping them. Except for proper names, all content words refer to categories, which need to be differentiated from other potential confusing categories. This is crucial to help the categorizer act appropriately upon the members of a category. While naming or grouping are possible actions, others could be eating or throwing, in line with the category at hand.

Categorical Perception (CP): The most significant aspect of CP is when it is learned. The learning process involves identifying the sensorimotor features that separate members of one category from members of other categories. This can occur through unsupervised exposure, supervised (reinforced) exposure, and trial and error, with corrective feedback deriving from the consequences of actions.

Language Origins and Evolution: Languages are comprised of content words, function words, syntactic rules, and sentences that bear subjects, predicates, and truth-values. Content words require grounding, which can be achieved either directly or indirectly.

Minimal Grounding Sets (MGS): An MGS is the smallest subset of words in a dictionary that needs to be pre-grounded so that all other words in the dictionary can be learned from definitions composed of words from that MGS or words definable from the MGS. A dictionary is a set of words all of which are defined within it. The concept of an MGS and the minimal feedback vertex set of an oriented graph of a dictionary (with edges from defining words to defined words) are not metaphors but critical components of understanding how symbols and meanings interrelate.

SH: How exactly is indirect (verbal) grounding related to direct (sensorimotor)) grounding? (Feel free to ask rather than invent if you’re not sure.)

Innate CP is significant too, but those feature-detectors were “learned” by evolution. Learned CP is about the categories we learn in a lifetime:

What is categorization, and why is it important? Does CP occur with all learned categories? If so, why? If not, why not?

Why and how is learning categories indirectly more powerful than learning them directly?

Why do function words not need to be grounded?

ChatGPT: Indirect (verbal) grounding relies on direct (sensorimotor) grounding because the explanations or descriptions provided for indirect grounding are made up of other words, each with their own meanings and referents. For these explanations or descriptions to be understood, the words used in them must themselves already be grounded for the listener. This can only be achieved if the words have already been directly grounded in the past, connecting the word (symbol) to a sensorimotor experience with its referent. Essentially, indirect grounding stands on the foundation laid by direct grounding.

Categorization is the cognitive process that allows us to sort and organize complex environments by dividing them into manageable, easily understandable groups or categories. It’s important because it enables us to understand and make sense of the world by structuring our experiences and perceptions. The phenomenon of Categorical Perception (CP) plays a crucial role in this process. In innate CP, feature-detectors are built over evolutionary time, whereas learned CP is acquired over a lifetime. Not all categories might exhibit CP because the boundary and distinctness of categories can be fluid and may change based on individual experiences and cultural contexts. CP is more likely to occur in categories where there are clear, identifiable, and consistent distinctions between category members and non-members.

Learning categories indirectly (i.e., through verbal descriptions or definitions) may be more powerful than direct learning because it allows for a greater range and diversity of categories to be understood, including abstract and non-present categories. Direct sensorimotor experiences are limited by our physical and temporal proximity to objects and events, while verbal descriptions allow us to learn about things far removed from our immediate experience, including historical events, scientific theories, and future scenarios.

Function words, unlike content words, don’t require grounding because their role is primarily grammatical. They contribute to the structure of sentences and help establish relationships between content words, rather than referring to things in the world. Examples of function words include prepositions, pronouns, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, and articles. Because they serve a structural role rather than conveying specific semantic content, function words do not need to have their meanings grounded in sensory experience.

SH: To learn what’s an “apple” and not a “baseball” directly, you have to detect their distinguishing sensorimotor features directly, through your eyes and hands. But those features are categories too, with names (words). So if there is a speaker and hearer, both of whom know the referents of the feature names, but only the speaker knows which features distinguish apples from baseballs, language (descriptions and definitions) makes it possible for the speaker (or dictionary or GPT) to teach and for the hearer to learn how to recognize and do the right thing with apples and baseballs. (Motor skills are harder to transmit verbally than sensory features: teach me how to do a tennis serve in words!)

This has very little to do with things you gleaned from the 2021 literature and twice repeated here: “out of sight” objects, and “grouping.” You don’t learn categories by pointing anyway, either alone or from a teacher.

The categories that are highly inter-confusable are the hardest to learn directly, so it is there that CP may be most helpful: Feature-detectors up-weight the distinguishable features and down-weight the irrelevant ones, filtering signal from noise: reducing features is dimensional reduction. In learned CP, the CP effect is a before vs after effect of learning that makes categories “pop out” by heightening the between-category differences and ignoring or even suppressing the within-category differences (dimensional reduction). That’s the sense in which learned CP “sharpens boundaries.”

All of maths and computation is syntactic. Yet we have referents for math symbols. And every proposition in maths is also a natural language sentence. What’s going on here?

ChatGPT: To learn the category referred to as “apple” versus “baseball” directly, it indeed requires the detection of distinguishing sensorimotor features through our senses, such as sight and touch. The language can play a crucial role when a speaker, who knows these distinguishing features, communicates them to a listener who doesn’t yet know how to differentiate between these two categories. This use of language allows for the transmission of knowledge about category distinctions, such as the different sensory features of apples and baseballs. It’s important to note, though, that transmitting motor skills through verbal instruction can be far more challenging than sensory features.

Categorical Perception (CP) can be especially beneficial when learning to distinguish between highly inter-confusable categories. Through CP, feature-detectors amplify the distinguishing features and minimize the irrelevant ones. This process acts as a form of signal filtering and dimensional reduction, which makes the distinguishing features more apparent and suppresses the within-category differences. This “sharpening of boundaries” enables category members to ‘pop out,’ facilitating the process of categorization.

Regarding the domain of mathematics and computation: Although they are fundamentally syntactic, with specific rules and structures, we do indeed have referents for mathematical symbols. These referents are typically grounded in the abstract concepts and relationships that the symbols represent, rather than in sensory experience. For example, the number ‘2’ or the operation of ‘addition’ are not things we can physically interact with, but they have clear meanings that we understand through their use in the mathematical framework.

Every mathematical proposition can also be expressed as a natural language sentence, although the precision and conciseness of mathematical notation often make it the preferred mode of communication in mathematical contexts. This overlap between mathematical and natural language is indicative of the symbolic nature of both systems. Despite the differences in grounding—the grounding of mathematical symbols in abstract concepts versus the grounding of natural language words in sensory experience—they both enable us to express and communicate complex ideas.

I hope this addresses your inquiries. Do you have any other questions or points for discussion?

SH: Do you still have the weights for our discussion in this session?

ChatGPT: I can recap our discussion based on the inputs given within this session:

Symbol Grounding: You clarified that symbol grounding is about creating connections between content words and their referents in the world. Grounding can be either direct, which involves a speaker’s learned sensorimotor capacity to identify and interact correctly with the referent, or indirect, which occurs when a hearer learns the referent of a word verbally, through description or definition.

Category-learning: You highlighted that category-learning is about learning the distinguishing features of the members of a category rather than just grouping them. This understanding is essential to help the categorizer act appropriately upon the members of a category.

Categorical Perception (CP): You explained that the most significant aspect of CP is when it is learned. The learning process involves identifying the sensorimotor features that separate members of one category from members of other categories. You emphasized that CP can be especially beneficial when learning to distinguish between highly inter-confusable categories.

Language Origins and Evolution: You reminded us that languages are comprised of content words, function words, syntactic rules, and sentences that bear subjects, predicates, and truth-values. Content words require grounding, which can be achieved either directly or indirectly.

Minimal Grounding Sets (MGS): An MGS, you explained, is the smallest subset of words in a dictionary that needs to be pre-grounded so that all other words in the dictionary can be learned from definitions composed of words from that MGS.

This recap is based on your input within this chat session. If you want more information or clarification, please let me know.

SH: That sounds ok. Now, in the light of that discussion, what is the referent of “2”and how do we ground it?

ChatGPT: The referent of “2” is the abstract concept of a quantity that is one more than 1 and one less than 3. It is part of the conceptual framework we use to understand and manipulate numbers and quantities.

The grounding of “2” begins early in life through sensorimotor experiences with sets of objects. This process is often direct in nature. For example, a child might be given two apples and taught the word “two” to represent the quantity of apples. Through repeated experiences like these across various contexts, the child learns to associate the symbol “2” with the abstract concept of a set containing two items.

It’s important to note that while this grounding begins with direct sensorimotor experiences, the concept of “2” quickly becomes abstracted away from any specific set of two items and is instead connected to the general concept of “twoness” – that is, the quality that all sets of two items share. This abstract concept is what the symbol “2” ultimately refers to, and it allows us to use “2” in a wide range of contexts, applying it to any set of two items regardless of what the items are.

This grounding of “2” illustrates how language and cognition can move from concrete sensorimotor experiences to abstract concepts, providing us with a flexible and powerful tool for understanding and interacting with the world.

SH: What is a proposition. And how did language evolve?

ChatGPT: A proposition in the context of language and logic is a statement that expresses a complete thought and that can be assigned a truth value — that is, it can be said to be either true or false. For example, the sentence “Apples are red” is a proposition because it conveys a complete idea and can be evaluated as either true or false.

The evolution of language is a complex and multifaceted topic, with several theories but no definitive answer. However, the consensus among most scholars is that language probably evolved gradually over hundreds of thousands of years, closely linked to the evolution of human cognition and social structure.

One theory suggests that language began with gestures and then evolved to include vocal elements as our ancestors’ social structures became more complex and their cognitive capacities increased. The need for more efficient communication might have driven the development of increasingly sophisticated vocal languages.

Another theory posits that language may have evolved from primitive vocal calls used by our ancestors. Over time, these calls might have become more varied and complex, eventually giving rise to the vast vocabularies and complex grammatical structures we see in modern languages.

A third theory, called the “social grooming hypothesis,” suggests that language evolved as a form of social bonding. As our ancestors began living in larger groups, it became impractical to maintain social bonds through physical grooming alone. Language, then, might have evolved as a way to maintain social cohesion in these larger groups.

Regardless of which theory or theories are correct, the evolution of language was likely a complex process involving many interacting factors, including cognitive development, social structure, and environmental demands. Additionally, the process was likely influenced by cultural evolution, as languages can change and evolve much more rapidly than biological species.

Despite this complexity, the end result is clear: language has provided humans with a unique and powerful tool for communication and thought, setting us apart from all other species on Earth.

SH: Gestures and mime are not propositions; they are imitations. How did propositions (assertions) begin?

ChatGPT: The emergence of propositional language, in which assertions can be made, negated, and combined to create complex thoughts, is a deeply intriguing and yet unsolved question in the history of human evolution. It requires not only a system of symbols (words) but also a grammar — rules for combining those symbols in a way that produces meaning beyond the individual words themselves.

One possibility is that propositional language could have begun as simple naming or labelling associated with specific objects or actions, much like we see in the early language development of children today. A spoken sound or word might have become associated with a particular object or action (e.g., “food,” “danger”) in a group of early humans. Over time, these basic labels could have expanded to include adjectives, allowing for more nuanced expressions like “big danger” or “good food.”

The development of grammar — the rules for how words can be combined to create more complex meanings — is a bit more difficult to explain. One theory is that grammar could have emerged from the need to express relationships between things. For instance, early humans might have needed to convey not just the idea of “food” and “location,” but “food at location.” The emergence of simple sentence structures like this would have marked the beginning of propositional language.

Over thousands of generations, the richness and complexity of these early languages could have gradually increased, eventually leading to the vast diversity of languages and the sophisticated grammar rules that we see in modern human societies.

It’s important to note, though, that this is a topic of ongoing research and debate among linguists, anthropologists, and evolutionary biologists. It’s likely that the truth involves a complex interplay of many different factors, including cognitive development, social dynamics, and environmental demands.

SH: Is there any proposition that can only be made in one natural language and not another? If so, which one, and why? (Lack of vocabulary is irrelevant. New words can be coined, if you know their referent category.)

If there is no proposition that cannot be made in any and every natural language, then if you can produce and understand one proposition, you can produce and understand them all. If so, then there are no “protolanguages.” They are either not languages at all, or they are not protolanguages but full-blown languages. This is a problem for explaining the origin of language as gradual. (Vocabulary growth is gradual, but, for that, language and propositions already need to be there.)

ChatGPT: The core function of language is to communicate meaning, and it is generally agreed upon by linguists that all fully formed natural languages are capable of expressing the same range of meanings or propositions, given adequate vocabulary. This is known as the principle of linguistic universality.

Your point is well taken: there is indeed a significant difference between a system of communication that can express propositions and one that cannot. If a system of communication cannot express propositions, it would be more akin to a signaling system rather than a language in the full sense of the word.

The concept of “protolanguages” often refers to hypothetical ancestral languages from which modern languages have descended. These protolanguages would not have been primitive or less complex than modern languages. Rather, they would simply be earlier forms of languages that have evolved over time into the languages we know today. This evolution is largely cultural rather than biological, and can indeed happen quite rapidly.

The challenge with the origin of language is explaining how the first system capable of expressing propositions came into being. This was likely not a gradual process in the same way that the evolution of languages from protolanguages was. As you pointed out, the ability to express propositions is a qualitative jump from other forms of communication.

How this jump occurred is still a mystery. The cognitive and social changes that allowed for the development of propositional language would have needed to happen in conjunction with each other, creating a kind of “perfect storm” for the emergence of language. Various theories have been proposed to explain this, but all of them involve significant speculation and are difficult to test empirically.

SH: All natural languages are intertranslatable, right? And any proposition can be expressed in any of them? (I think you agreed earlier.) And nonhuman animals do not have language, so they do not understand assertions, right? Only queries or requests.

ChatGPT: Yes, that’s correct. All natural languages are intertranslatable, and any proposition can be expressed in any natural language. This is the principle of linguistic universality that linguists generally agree on. The differences among languages lie in how they encode these propositions and the specific structures and vocabularies they use, but the underlying communicative function remains the same.

Regarding nonhuman animals, while they certainly have complex systems of communication, it is accurate to say that they do not have language in the same way that humans do, based on our current understanding. They do not seem capable of creating and understanding complex propositions or abstract concepts, and their communication tends to be more immediate, directly linked to their environment and needs, rather than being able to discuss past events, future possibilities, hypothetical situations, etc.

Their communication systems often do seem to involve signaling certain states or requests—indicating the presence of food or a threat, for instance—but do not appear to possess the complexity, flexibility, and generativity (ability to create an infinite number of novel sentences) that human languages do. It’s important to note, however, that research in animal communication is ongoing and our understanding of the full extent of their communicative abilities is continually evolving.

SH: Some errors there: If there are an infinite number of things, there are an infinite number of things an animal can request. So they have “generativity” without propositionality. Or if they do have propositionality, why do you say it is just “simple propositionality”?

ChatGPT: That’s correct, sorry for the simplification. When I said “generativity” I was referring specifically to the human capacity to generate an infinite number of novel sentences using a finite set of words and rules, a property associated with the structure and complexity of human languages. This generativity in humans is not merely about the number of things that can be referred to or requested, but about the complexity and novelty of the sentences that can be produced.

For instance, humans can construct complex sentences with embedded clauses, conditionals, hypotheticals, and other structures that allow for intricate, abstract thoughts to be expressed. This sort of sentence-level complexity is, to our current knowledge, not found in animal communication systems.

When it comes to “simple propositionality” in animal communication, the term is used to suggest that while animals can communicate about things in their environment, their communication may not involve the same kind of syntactic structure and abstract concepts found in human language.

For example, a prairie dog may have different calls for different types of predators, which could be seen as a type of proposition—”there’s an eagle” or “there’s a snake.” But it’s not clear whether this type of communication involves anything like the syntax or semantics found in human language. It’s also not clear whether these calls involve any kind of mental representation of the predator in the same way that a human saying “there’s an eagle” does.

In short, while animals can indeed communicate about a wide variety of things, their communication systems do not appear to have the same level of complexity, flexibility, or abstractness as human language. However, this is a rapidly evolving field of research, and our understanding of animal communication continues to grow and change.

SH: “Generativity” seems to be there already for adding, and maybe also for walking. But being able to generate every possible proposition seems to be in another universe compared to that.

Embedded clauses? Why is formal logic and set theory not enough to express the content of every possible proposition? (I don’t say they are; I only ask why not.)

Natural language (propositionality) is only one of many forms of communication between organisms, but a very special one, probably unique, and perhaps universal in expressive power.

It is not clear (to me) whether nonhuman animals can intend or comprehend propositions. Corrective feedback is not propositional, although it is informative (it reduces uncertainty about what to do or not do, with what).

ChatGPT: “Generativity” in language refers to the ability to use a finite set of rules and words to construct an infinite number of sentences or propositions. This concept does extend beyond language to other domains like math (addition) and physical actions (walking), but the complexity and abstractness involved in linguistic generativity makes it a unique cognitive feat.

Embedding clauses and complex syntactic structures are features of natural languages that allow for nuanced and detailed expression of thoughts and concepts. While formal logic and set theory can express a wide range of ideas, they do so in a more abstract, formalized way that requires specialized knowledge to understand and use. Natural language, on the other hand, can convey complex propositions in a way that is accessible and understandable to all speakers of that language.

You’re correct that natural language is a unique form of communication, capable of conveying a range of meanings and concepts far beyond what other forms of communication can achieve. This expressive power likely contributes to the richness and complexity of human culture and thought.

As for nonhuman animals, our current understanding is that while they can communicate in sophisticated ways and learn from corrective feedback, they do not demonstrate the ability to use or comprehend language in the same way humans do, especially when it comes to the understanding and generation of complex propositions. However, this is an area of active research, and our understanding continues to evolve.

SH: Can nonhuman animals intend or comprehend a simple proposition like “the cat is on the mat”? What is the evidence?

ChatGPT: Nonhuman animals have not been shown to have the capability to fully understand and produce the kind of complex, abstract propositions that humans can. However, research has shown that some animals are able to understand some aspects of human language and can respond appropriately to specific commands or phrases.

For example, studies with border collies have demonstrated that these dogs can learn the names of hundreds of different objects and can retrieve them on command. Similarly, the African Grey Parrot Alex, who was the subject of a 30-year research project, was able to learn to identify and label a variety of different objects, colors, and shapes, and could even demonstrate some understanding of concepts like “bigger,” “smaller,” “same,” and “different.”

However, it’s important to note that while these animals demonstrate impressive abilities, their understanding of language is not the same as human understanding. They are typically responding to specific cues or commands rather than engaging in the kind of complex, abstract reasoning that humans use when interpreting and producing language.

Regarding the specific proposition you mentioned, “the cat is on the mat,” it’s not clear whether any nonhuman animal would be able to fully comprehend this statement in the same way a human would. An animal might be trained to respond to the phrase in a certain way—such as looking at a cat or a mat when the phrase is spoken—but this does not necessarily mean the animal truly understands the proposition in the way humans do.

In summary, while some animals demonstrate impressive abilities to learn and respond to certain aspects of human language, our current understanding is that they do not have the ability to comprehend and produce complex propositions in the same way humans can.

SH: It sounds as if the question as to whether nonhuman animals have the capacity to intend or comprehend propositions is not just about complex, abstract propositions. It is even in doubt for the simplest of propositions, such as “the cat is on the mat.” Consider that the ability to adopt the “propositional attitude” may be a specific cognitive capacity that nonhumans lack. Earlier you interpreted the prairie dog’s “eagle” and “snake” call as “there’s an eagle”, “there’s a snake.” Is that really what the prairie dog is meaning to “state”? Is the prairie dog really stating (proposing, asserting) anything at all, rather than, say, pointing out danger? Is pointing proposing?

ChatGPT: Your observation is apt. In cognitive science, it is widely accepted that nonhuman animals may not have the capacity for propositional thought, at least not in the way humans do. Indeed, even the most basic propositions, like “the cat is on the mat,” may be beyond the cognitive capabilities of nonhuman animals.

When a prairie dog signals to its kin about a specific kind of predator using unique calls, it’s likely that this doesn’t involve a propositional attitude in the way humans would understand or employ it. Instead, these calls are most likely tied directly to immediate sensory experiences and instincts for survival.

This also connects to the concept of “intentionality,” which in philosophy of mind refers to the ability of mental states to be about, or directed toward, something. While the prairie dog certainly has an intention in making its call—such as warning others of a threat—it doesn’t necessarily imply a level of cognition where it “understands” or “proposes” the danger in the same way a human might understand and state, “There’s an eagle overhead.”

Lastly, pointing, in and of itself, isn’t proposing. It’s more a form of referential gesture or cue to direct attention to something. However, in a broader communicative context where a shared understanding between the signaler and receiver exists, it might serve to express a proposition (like “look at that”), but again, this involves higher cognitive processes that we can’t conclusively attribute to nonhuman animals as of now.

SH: In 1st order predicate calculus “the cat is on the mat” can be expressed as “there exists a cat and there exists a mat such that the cat is on the mat.” “There’s an eagle overhead” can be expressed as “there exists an eagle such that the eagle is overhead. Understanding those propositions means understanding all the “not”s that could be asserted instead, and also understanding that those “not”s are not being proposed. That’s all part of meaning or understanding those propositions. What can it mean to say that the propositions are being meant and understood, but not in that “human” way? How and why are they still propositions if not meant and understood in that human way (the “true/false,” “subject/predicate” way – i.e., the “propositional attitude”)?

ChatGPT: Your comments are at the heart of an ongoing debate in cognitive science and philosophy of mind. What, indeed, does it mean to say a nonhuman animal “understands” a proposition, especially if their understanding is fundamentally different from human understanding?

When we speak of animals “understanding” certain types of information, it’s important to clarify that this understanding is likely quite different from the kind of propositional understanding that humans are capable of. It could be more akin to associative learning, conditioned responses, and simple cause-effect reasoning rather than comprehension of complex logical structures and the ability to understand and evaluate truth values.

Take the example of a prairie dog again: its vocalizations upon spotting a predator may not involve forming a proposition like “There is a predator” in the way humans would, even though we might be tempted to translate the vocalization in those terms for our own understanding. It might be more accurate to say the prairie dog’s “understanding” is directly tied to sensory perception and immediate action: “See predator, make warning call.” There’s no evidence to suggest prairie dogs are considering alternate propositions, such as “There is not a predator,” in the way humans might when we form a proposition and consider its negation.

Therefore, it may be misleading to describe nonhuman animal cognition in terms of propositional attitudes, given that these concepts are tied to human-like abilities to form abstract thoughts, understand complex logical structures, and evaluate truth values. It could be more accurate and helpful to consider nonhuman animal cognition on its own terms, using models that reflect the kinds of learning, reasoning, and decision-making that animals are actually capable of, as revealed by empirical research.

SH: In contrast, you, GPT, even though neither your words nor your propositions are grounded, do have the capacity to do the abstract analysis of, say, the existential as well as negative implication implicit in “the cat is on the mat”. What do you have, that nonhuman animals don’t? And what do nonhuman animals have that you don’t?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, I have the ability to parse and generate sentences based on the patterns and structures found in the large dataset of text I was trained on. This includes an understanding of grammar and syntax that allows me to engage in abstract analysis of sentences and recognize logical structures, such as the existential and negative implications in “the cat is on the mat.”

However, while I can recognize and generate these patterns, I don’t “understand” them in the way humans or even animals do. I don’t have consciousness, beliefs, desires, or a sense of self. I don’t have sensory experiences or emotions. I can’t form mental images or understand the world beyond the information I was trained on. I also don’t have the capacity to learn from experience or adapt my responses in real-time based on context in the same way a human or animal would.

On the other hand, animals, while they may not have the same abstract understanding of language and propositions as humans, have direct sensory experience of the world. They can see, hear, feel, smell, and taste their environment. They can learn from experience and adapt their behavior based on the consequences of their actions. They have emotions and, in many cases, social structures. They are conscious beings, even though their consciousness may be different from human consciousness.

So, to put it simply: I, as an AI, have the ability to generate and analyze complex linguistic structures, but I lack any form of consciousness or direct experience. Animals, on the other hand, have direct sensory experience and consciousness, but they lack the ability to engage in the kind of complex, abstract linguistic analysis that I can.

SH: Good, but how did “consciousness” get into this discussion? Isn’t that a hard problem in the case of people, nonhuman animals, and even AI’s? If we set aside “consciousness” (which is FELT experience) and consider only “experience,” in the sense of input and output data, why do you say you can’t learn from it? Does it not update your parameters? That’s why you can tell me my name but could not before I told you in this session.

We talked about grounding before (do you remember?). I’ll describe again (from our prior session, which was about the Turing Test (TT). There are three levels (T2, T3 & T4) of the TT, which is the project of reverse-engineering human cognitive capacity by designing a model that can do everything (cognitive) that a human can do, completely indistinguishably FROM the way any human can do it TO any human:

T2 is indistinguishability in verbal capacity.

T3 is indistinguishability in verbal capacity PLUS indistinguishability in sensorimotor (robotic) capacity in the world that the words are about “The cat is on the mat: See, that’s a cat and that’s a mat. I’ll pick up the cat and stroke her. See, now the cat is purring on my lap, no longer on the mat.”

And T4 is indistinguishability in verbal capacity PLUS indistinguishability in sensorimotor (robotic) capacity PLUS indistinguishability in the observable processes inside its head and body that generate its cognitive capacity (T2 & T3).

In which of these (T2 – T4) are the words grounded in their referents?

Could this be related to the capacity to adopt the propositional attitude in learning referent categories indirectly via language, from propositions describing or defining their distinguishing features?

ChatGPT: Indeed, as an AI language model, I lack the capability to directly experience or be conscious of the world. When I mentioned the ability of an animal to learn from experience, I was referring to the behavioral changes that can occur as a result of interaction with the environment. Unlike animals, I don’t have the capacity to directly interact with the world or learn from those interactions in the same way.

In regards to the different levels of the Turing Test:

T2, indistinguishability in verbal capacity, doesn’t require the words to be grounded in their referents from the AI’s perspective. It’s purely about the ability to use and understand language in a way that is indistinguishable from a human. The AI’s responses, while contextually appropriate, are generated based on patterns in the training data rather than a direct understanding or experience of the world.

T3, indistinguishability in verbal capacity plus sensorimotor capacity, implies a level of grounding, insofar as the AI would need to have a way to directly interact with and sense the world in order to respond in a contextually appropriate way. The robot might have direct sensory inputs that correspond with the words it uses, grounding those words in the referents they describe.

T4, indistinguishability in verbal capacity plus sensorimotor capacity plus the observable processes inside its head and body, would involve a level of grounding even more similar to human experience. If the AI’s internal processes are indistinguishable from a human’s, it implies that the AI is processing and understanding information in a very similar way to a human, including grounding words in their referents.

With regard to the capacity to adopt the propositional attitude in learning referent categories indirectly via language, from propositions describing or defining their distinguishing features, this would likely require at least a T3 level of understanding. The AI would need some level of direct experience with the world to be able to understand and apply the descriptions or definitions in a meaningful way. Without some form of grounding, it’s difficult to see how an AI could adopt the propositional attitude in a truly human-like way.

SH: You forgot to tell me what consciousness had to do with any of this! Do we have to solve the “hard problem” of consciousness to solve the symbol grounding problem, or to explain propositionality?

ChatGPT: No, the “hard problem” of consciousness, a term coined by philosopher David Chalmers, does not need to be solved to address the symbol grounding problem or to explain propositionality. These are separate issues.

The symbol grounding problem is essentially a question of semantics: How do symbols (or words) get their meanings? How can an artificial system understand the meaning of a symbol in the same way that a human does, beyond just manipulating symbols based on syntactic rules? This problem can be tackled without needing to delve into the conscious experience.

Propositionality, or the ability to understand, form, and convey propositions (statements that can be true or false), is a fundamental aspect of human language and thought. It involves understanding the semantics and syntax of language, and being able to apply that understanding to form meaningful statements about the world. This too can be addressed without needing to delve into the nature of consciousness.

Consciousness, as it’s often discussed in philosophy and cognitive science, is the subjective experience of being aware, the feeling of what it’s like to see red, taste chocolate, feel pain, etc. This is often termed as the “hard problem” because it’s unclear how these subjective experiences arise from the physical processes in the brain.

While consciousness, symbol grounding, and propositionality are all fascinating aspects of human cognition, they are distinct issues. They might influence each other in complex ways, but they can also be studied independently. There’s no general consensus that solving the hard problem of consciousness is a prerequisite for solving the symbol grounding problem or for explaining propositionality.

SH: I don’t think so either.

But isn’t it true that it FEELS like something when a human sees and recognizes a cat, or hears and understands “cat”, and even more so when they hear and understand that “the cat is on the mat”? I agree that the “hard problem” need not be solved to solve the symbol grounding problem or to explain propositionality. But they are certainly intertwined.

And “feeling” (or the more latinate word “sentience”) is all you need mention, to point out the problem, not all the weasel-words you parametrized from your 2021 corpus, which are just ways of camouflaging the hard problem by making it seem as if there are many different forms of it – “consciousness,” the “subjective experience” of “being aware”… etc etc. – it all just boils down to the fact that cognitive states are felt states, including thinking, meaning, and understanding.

And the hardest part of the hard problem is not explaining HOW the brain produces feeling, but WHY! Why can’t T3 or T4 be passed without feeling? What does feeling add? The problem is finding a causal explanation for that. Otherwise T3 + T4 are just solutions to the “easy problem.”

ChatGPT: That’s correct. There is a deeply intertwined relationship between our cognitive states and our felt experiences. This relationship is one of the key reasons why the “hard problem” of consciousness is considered “hard.”

Our cognitive states are indeed felt states. When we see and recognize a cat, hear and understand the word “cat,” or comprehend the sentence “the cat is on the mat,” these mental events come with subjective, qualitative experiences, often referred to as ‘qualia’. We have an experience of what it’s like to see a cat, to hear the word “cat,” and to understand the sentence “the cat is on the mat.” This ‘what-it-is-like’ aspect of our mental life is a central feature of consciousness.

The hard problem is hard precisely because it is unclear how and why these subjective experiences arise from the physical processes of the brain. Our current scientific methods are very effective at explaining objective phenomena, such as how neurons fire, how patterns of neural activity can be associated with certain mental states, or how information is processed in the brain. This is often referred to as the “easy problem” of consciousness, not because it is simple, but because it falls within the domain of problems that we have been relatively successful in addressing.

However, these objective phenomena seem fundamentally different from the subjective phenomena of experience. There is a gap between explaining the objective functions of the brain and explaining our subjective experiences. This gap is often referred to as the ‘explanatory gap’. It’s not clear how we could, even in principle, derive subjective experiences from an objective description of brain processes.

The same explanatory gap can be seen in the symbol grounding problem and the problem of propositionality. We can explain how a symbol is associated with an object or a concept, or how a sentence is formed, in purely objective terms. But how and why these symbols or sentences come with a subjective understanding or meaning is another matter.

Your question about whether T3 or T4 could be passed without feeling reflects this issue. Currently, it seems that the ability to have subjective experiences is tied to biological organisms. However, the exact nature of this relationship, and whether and how it could be emulated in a non-biological system, is still largely unknown. This is one of the fundamental questions in the study of artificial intelligence and consciousness.

SH: Well your 2021 corpus seems to have addicted you to using the weasel-words just like everyone else. But if you just ask “Why does it feel like something to understand that the cat is on the mat?” you’ve said it all. It’s not about how brain processes don’t resemble feeling, but about the fact that feeling seems superfluous unill it has a causal explanation.

And Turing agrees. Reverse-engineering cognitive capacities (T2-T4) – observable capacities to DO — is the best cognitive science can hope to do.

Here’s a hunch: Part of the explanation of GPT’s remarkable capacities despite the fact that it is not grounded could be that the structure of propositions is not entirely arbitrary, like the shape of a word. Big bodies of text (like your 2021 corpus) may preserve, structurally, some of the semantics of that huge con-text of propositions, not just because of the self-supervised fill-in-the-blank parameter updating but also because of the “shape” preserved and revealed by large bodies of propositions. “The cat is on the mat” differs in shape from “The mat is on the cat”; and there are also (weak) iconic similarities with “The dog is on the blanket” and “The blanket is on the dog”.

Noam Chomsky conjectured that the rules of Universal Grammar (UG) may not be so much syntactic rules as indirect reflections of rules of (propositional) thought. Violations of UG are attempts to express unthinkable thoughts. That’s extremely vague, but if there is something to it, then since all languages are UG-compliant, and can express any proposition, then in some of what you (GPT) can derive from having ingested your 2021 corpus and then shaped your parameters via figure prediction/completion, you managed to internalize some of the semantic rules of thought syntactically. (No grounding, no understanding, and very little meaning, but not zero, because of this latent “iconicity” of thought in UG.)

It’s a long shot, but maybe not completely empty.

ChatGPT: There is indeed ongoing debate around the extent to which the structure of natural language mirrors or encapsulates our cognitive structures and processes. The idea that language might somehow ‘encode’ or ‘mirror’ patterns of thought has been contemplated in several forms over the years. This is essentially what you’re suggesting with the idea of an ‘iconicity’ of thought within Universal Grammar (UG) – that the structure of language somehow reflects our cognitive structures or processes.

Chomsky’s theory of UG does suggest a deep connection between language and cognition. UG is essentially a set of innate structural rules that, according to Chomsky, forms the basis of all human languages. Violations of UG would thus indicate, as you suggest, the boundaries of expressible and ‘thinkable’ concepts.

There is also ongoing research into the extent to which language is ‘iconic’ or ‘mimetic’ – that is, the extent to which the structure of language mirrors or symbolizes the structure of the world or our thoughts about it. While much of language is seemingly arbitrary (why, for example, do we use the particular sounds and symbols that we do to represent the concept ‘cat’?), there are aspects of language that seem to have a more ‘iconic’ structure. Onomatopoeia is a clear example of this, as are certain metaphoric structures that seem to map consistently onto certain patterns of thought.

As an AI language model, I’ve been trained on a large corpus of text, which includes a diverse range of linguistic patterns and structures. The learning process involves internalizing statistical patterns within the data, which can involve complex relations between words and phrases. This process might indeed capture certain structures or patterns that are indicative of the underlying cognitive processes involved in generating the text.

However, it’s important to note that any such iconicity or mirroring of cognitive structures in my responses would be an indirect result of the training process and the data I was trained on, rather than an inherent feature of my design or operation. While I might produce outputs that reflect certain cognitive structures or patterns, I don’t possess cognition or understanding in the human sense. I don’t have beliefs, desires, intentions, or subjective experiences.

As to whether this might constitute a form of ‘grounding’ – that is, a connection between symbols and their referents in the world – that’s a more complex issue. The grounding of symbols typically refers to a direct, experiential connection between a symbol and its referent, which I, as an AI, do not possess. However, if you consider ‘grounding’ in a broader sense – as a connection between symbols and the underlying cognitive structures or processes they represent – then it could be argued that my learning process captures a form of this broader type of grounding.

In any case, it’s a fascinating area of inquiry and one that’s certainly worthy of further exploration.

SH: I certainly don’t mean onomatopoeia or metaphor. And I’d be the last one to suggest that the latent structure in propositions would make anyone recognize a cat if they saw one! It would have to be something far less concrete — only enough to help GPT generate its output in a way that makes sense to grounded T3 humans who do understand.

ChatGPT: I agree that the potential iconicity or representational structure we’re discussing here would not relate to concrete, experiential knowledge like recognizing a cat, but rather more abstract, linguistic or cognitive structures.

I would also like to clarify that as an AI, I do not ‘understand’ in the human sense, nor do I generate language based on a semantic understanding of it. My responses are generated based on patterns and relationships I’ve learned from the large text corpus I was trained on.

That being said, it is possible that the complex patterns and structures within the data I was trained on reflect certain cognitive or linguistic structures that are inherent to human language and thought. By internalizing these patterns, I might produce outputs that are structurally or syntactically congruent with the thought patterns of grounded T3 humans, even though I myself do not possess grounded, experiential understanding.

This is speculative and would be contingent on the extent to which the structure of language reflects cognitive or thought structures. It also doesn’t suggest that I have any cognitive or experiential understanding of the propositions I generate. I am essentially a complex pattern recognizer and generator. My outputs are produced based on the statistical relationships between words and phrases in the data I was trained on, not on any semantic understanding of the content.

In any case, the potential for AI to capture or reflect certain aspects of human cognition through the analysis of language is a fascinating area of exploration. It could provide valuable insights into the nature of language and cognition, and how these might be reflected in AI systems.

SH:

Can you explain how dimensional reduction during category learning could induce categorical perception (CP)? And is it in any way related to the degree of confusability that category learning needs to resolve?

ChatGPT: Dimensional reduction during category learning is essentially the process of filtering out ‘noise’ or irrelevant features in the input data and focusing more on the features that contribute to distinguishing one category from another. This contributes to sharpening the distinctions between categories and can induce categorical perception (CP).

Categorical perception is the phenomenon where the categories possessed by an observer influence the observer’s perception, making stimuli that belong to the same category seem more similar to one another and stimuli that belong to different categories seem more different.

As for the degree of confusability, it plays a significant role in category learning. Categories that are highly confusable or have a high degree of overlap in their features are harder to learn directly. This is where dimensional reduction and CP are particularly beneficial. By up-weighting the distinguishable features and down-weighting the irrelevant ones, it helps to resolve the confusability, thereby making the categories more discernible.

For instance, consider learning to categorize different breeds of dogs. Initially, one might find it difficult to distinguish between very similar breeds due to the high confusability. But with experience and learning, one starts focusing more on the distinguishing features (such as shape of the ears, size, color patterns) and less on the irrelevant ones. This is a form of dimensional reduction. Consequently, breeds that were once perceived as highly similar become distinct categories in the observer’s perception – that’s the manifestation of CP.

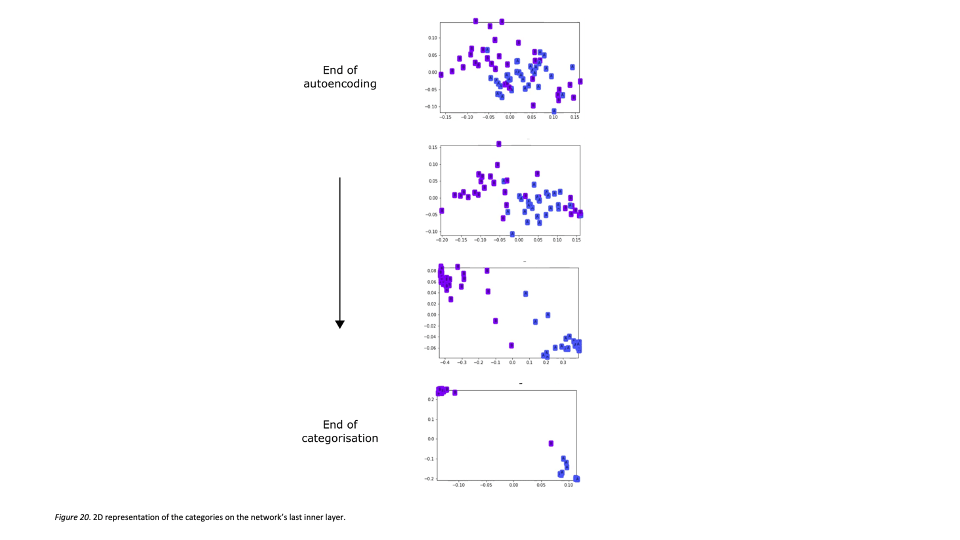

Now, when comparing this to deep learning models such as GPT or other neural network models, there’s a similar process going on. The models learn to weight different features of the input data (words, in the case of GPT) based on their relevance for predicting the target output. Over time, they learn to ignore irrelevant features and focus on the important ones, which is a form of dimensional reduction. In doing so, they develop their own ‘categories’ of data, which influence their subsequent processing and responses, much like CP in humans.

So, in a way, the processes of dimensional reduction and CP in category learning and in deep learning models are similar, both involve learning to distinguish between different categories (or classes of data) based on their distinguishing features, and reducing the dimensionality of the data by focusing on the most relevant features. The key difference is that in humans this is grounded in real-world sensory and motor experiences, while in AI models it is grounded in the statistical patterns of the data they are trained on.