Mary Rose

I took a trip with work colleagues yesterday to check out the new Mary Rose museum. For those international readers who may be unfamiliar with “Britain’s Pompeii” Mary Rose is a Tudor warship that sank in Portsmouth Harbour during a battle with the French. Half the hull, and an amazing number of objects were preserved in the silt, and the site has been a marine archaeological “dig” for decades.

The new museum was built around the hulk of the vessel, which has been in-situ in a Portsmouth dry-dock since it was raised back when I was a kid.

In black wood, the building’s ark-like shape echoes the ship it contains. Inside, there are galleries that run along the length of the Mary Rose, displaying some of the objects in the mirror image of the position that they were found in the wreck . For example, one of the things that most excited me was the brick-built cooking facility right down on the bottom deck of the ship. Between these galleries and the Mary Rose herself, there is currently a wall, with windows of varying shapes and sizes allowing you to peer through. The wooden structure is still being conserved. Having been chemically sprayed for 20 years or so, it’s now being air-dried, and in about five years the wall between the ship and its visitors will come down. When that happens (I hope and expect) visitors will be able to glance across from an interest object (like my kitchen) and recognise the place it occupied in the wreck. At the moment, its slightly frustrating because visitors can’t make that connection without having to shift position and peer from one of the windows.

One great aspect of these long galleries is that their floors are not level but curve just like the decks of the Tudor ship. With some of the displays encouraging visitors to step into spaces with limited headroom, the physicality of the space does a very good jobs of putting you “on board”, without compromising access.

At either end of the museum there are more conventional (level) interpretive galleries, thematically unpacking a wealth of the objects that were found onsite. Vitrines and interactive displays interpret life on board the Mary Rose as well as the archaeological methods used to reach a shared understanding of what life might have been like.

Reflecting on the experience as a whole, and considering it through the lens of where my studies have taken me so far, it’s pretty traditional museum experience, there’s an emotional peak at the beginning, as you walk into the first gallery past an evocative video that puts you among the sailors as the ship turns on its side and water floods in. Then there’s a context setting exhibition which helps you start to define your route through the plethora of objects in vitrines that you are about to see. I felt no pressure to look in detail at every vitrine, though colleagues reported becoming quickly overwhelmed by the sheer number of objects to look at. Certain objects caught my eye and excited me, but there wasn’t another “designed” emotional peak until the route required taking a lift between the lowest floor and the highest. as the lift began its ascent, the interior lights dimmed, and we were blessed with a view of the whole hulk of the ship through the glass side of the lift. No longer obcsured by wall and glimpsed through windows, the sight was magnificent.

But after the little epiphany I had in this post, I was looking for another emotional peak, or moment of insight at least, as I left the final gallery. I was disappointed. All I got was some underwhelming footage of the salvaged Mary Rose making her way towards the shore at Portsmouth. I tried to remember the excitement I felt watching it on TV in 1982, but failed to make my heart beat faster.

It reminded me of a conversation I recently had with my boss, about this very subject. She use to work for the visitor attractions company which runs SeaLife centres, Tussauds, etc and told me that there, no project got off the ground that didn’t have a final wow moment of some sort. So it isn’t rocket science, why do so many cultural heritage attractions end with such a damp squib before the gift shop?

There are a couple of simple games included among the interactives. In one, visitors co-operate to become marine archaeologists. One player moves a diver equipped with an underwater “blower” around the seabed, looking for objects to uncover. As each object becomes visible the second player moves their diver to “record” the object. A successful recording rewards the players with a little bit of interpretive text, but the object of the game is see how many pieces you can uncover and record before the divers’ air tuns out.

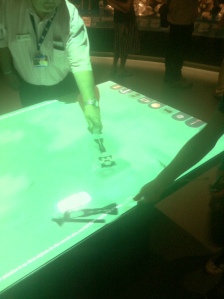

I had to force myself to stop playing the other game though, which was simple but addictive. Equipped with four ship’s cannon, of various sizes, the object of the game was to disable but not sink as many French ships as you can within the time limit. The enemy vessels cross the screen at various ranges. Use too weak a gun, and your shot will fall short, but too powerful a weapon will sink the ship and you lose your booty. I managed eleven ships with my second go.

One of the other interactives felt strangely dated. An early exhibit displays the Cowdray Engraving, a depiction of the battle showing just the tips of the Mary Rose’s masts as she sinks beneath the waves. Touch sensitive screens allow visitors to explore the map in detail and various points of interest are interpreted with pop-up windows. But I found myself trying to use multi-touch gestures to navigate, and got quite frustrated with the displays.

The other interactives took the role of text panels when “asleep,” with a few lines of text on a topic, but touch one of the object icons, or question buttons, on the panel and a video would appear. With some objects, for example, a pocket sundial, the video would show a recreation of the object in use. In other videos would feature experts talking about the object, or concept.

A short aside on the video reconstructions. Many of the sailors are portrayed wearing just a shirt and hose, with no other layers. The shirts were also surprisingly short. Given the detail of many other aspects of the reconstruction, and some of the amazing scraps of fabrics (including a check shirt, velvent and woollen cloth) that have been preserved by the silt, I wanted to know whether this was a considered, informed choice, or just cheap costuming. I didn’t find a conclusive answer.

Overall though, the museum is a moving and captivating experience. I know a little about Tudor life, but I learned so much from these objects, mundane, useful objects and felt a real connection with the men who lost their lives when Mary Rose sank. The museum considers itself a memorial to those sailors, and it’s a sensitive and well-deserved epithet.

![IMG_4263[1]](http://memetechnology.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/img_42631.jpg?w=300&h=224)