On Sirmione, jewel of peninsulars

Sirmio, jewel of islands, jewel of peninsulas,

jewel of whatever is set in the bright waters

or the great sea, or either ocean,

with what joy, what pleasure I gaze at you,

scarcely believing myself free of Thynia

and the Bithynian fields, seeing you in safety.

O what freedom from care is more joyful

than when the mind lays down its burden,

and weary, back home from foreign toil,

we rest in the bed we longed for?

This one moment’s worth all the labour.

Hail, O lovely Sirmio, and rejoice as I rejoice,

and you, O lake of Lydian waters, laugh

with whatever of laughter lives here.

Catallus Poems, 31 Sirmio

Last week, the family and I took a break in Italy. We stayed on the shores of Lake Garda, and the first thing we did, was visit one of the most important cultural attractions of the Lake, GardaLand.

But the very next day, we went to the southern peninsular, Sirmione. At the very tip of this rocky finger which, on the map at least, seems to command views right up to the Northern end of the lake, lie ancient Roman ruins.

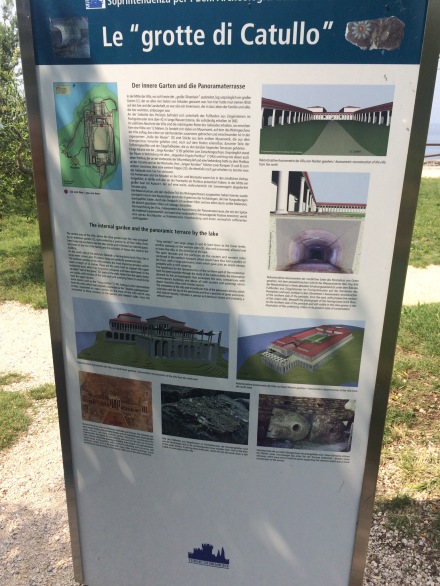

They are misnamed. Known, since the eighteenth century at least, as the Grotte di Catullo, most of the visible ruins date from long after that pre-Christian poet died. But as his poem (above) evidences, he did once live on the peninsular, and regard it as his home. And there is evidence of another, older, villa upon which the buildings that these ruins describe was built.

The scale of the place is fascinating. We arrived on the ferry from Peschiera del Garda, which is the very best way to arrive because it showcases the ruins as the ferry rounds the tip of the peninsular. From the water, the great brick and stone arches (which, if I read the interpretation correctly, comprise just the footings and undercroft of the villa) look huge. Their presence alone makes the massive scale of building five at Portus less surprising. You mind yourself thinking, as your boat chugs round to the dock, that this could not be some private villa, but surely, such an impressive building, which such a commanding view of the lake, must have had some sort of governmental purpose? The modelled illustrations on the interpretation boards play up the that sense of scale. And on a hot day (like the day of our visit) you wonder if you really want to take the walk from one end to the other. But then, you are surprised by the compactness of the site. Or at least I was. While walking among the pillars and columns, I was still impressed and overwhelmed by their height, but walking between them, traversing the site, across its width and length, and domestic scale reasserted itself, and yes, you can believe it might have been a villa (all-be-it an impressive one).

I mentioned the interpretation panels, and its worth returning to them. There’s a language problem – and its not that I don’t know any Italian. The panels were all double sided and repeated the same information in Italian, German, French and English. The problem was the language of archaeology. Take this example from the MiBAC introductory leaflet:

“…and to confirm the building currently to be seen was created as a single project defining its orientation and spatial distribution, following specific criteria of axiality and symmetry.”

My computer doesn’t even think “axiality” is a word at all, but I think I understand. The problem is, if I understand at all, its only because I’ve been hanging around with archaeologists quite a lot recently. And I don’t think this is a problem of poor translation from the Italian – the less jargon-y text is translated perfectly well. I think its evidence that the interpretation project could have benefited with a storyteller on the team.

I’m rushing off soon, so one final interesting note. The archaeological evidence shows that as the building fell into decline and disuse, it became a place to inter the dead. This is a practice that puzzles me and many fellow students on the Portus MOOC, yet it seems quite widespread. I wonder if the next iteration of the MOOC should explore this aspect even more…