Olgachka,

So much still left unsaid

A sequel ne’er to be

A life left poised on pause

For all eternityYou taught us how to live,

To give, unstintingly

Till life itself dealt cause

To end that revelryThose fatal cards — you chose

To lay down, not to play

To not reverse the roles

That yours were till that dayYour mother’s guardian angel,

Inspiration to us all

You need not have feared that phone call:

Ya Uzse Vsë Ponimal.Dorogoyka, pri vsekh moikh liubvi,

Stëpa

As It Is Written — On UK Busses (Jan. 2009)

There are probably neither gods nor tooth fairies.

So stop worrying, enjoy life, and do unto others as you would have them do unto you — not because it is Writ, but because it is right.

When “Knowledge Engineers” Say “Ontology” They Mean the Opposite: “Epistemonomy”

From the first time I heard it misused by computer scientists, the term “ontology,” used in their intended sense, has rankled, since it is virtually the opposite of its normal meaning. (And although terms are arbitrary, and their meanings do change, if you’re going to coin a term for “X,” it is a bit perverse to co-opt for it the term that currently means “not-X”!)

Ontology is that branch of philosophy that studies what exists, what there is. (Ontology is not science, which likewise studies what there is; ontology is <i>metaphysics</i>: It studies what goes beyond physics, or what underlies it.)

Some have rejected metaphysics and some have defended it. (In “Appearance and Reality,” <a href=”http://www.elea.org/Bradley/”>Bradley</a> (1897/2002) wrote (of Ayer) that ‘the man who is ready to prove that metaphysics is wholly impossible … is a brother metaphysician with a rival theory.”)

Be that as it may, there is no dispute about the fact that “ontology,” whatever its merits, is distinct from — indeed the complement of — “epistemology,” which is the study of how and what we <i>know</i> about what exists. In fact, one of the most common philosophical errors — a special favorite of undertutored novices and overconfident amateurs dabbling in philosophy — is the tendency to confuse or conflate the ontic with the epistemic, talking about what we do and can <i>know</i> as if it somehow constrained what there is and can <i>be</i> (rather than just what we can know about what there can be).

Well, knowledge engineering’s misappropriation of “ontology” — to denote (in the wiseling words of <a href=”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontology_(computer_science)”>Wikipedia</a>) “a ‘<a href=”http://tomgruber.org/writing/ontolingua-kaj-1993.pdf”>formal, explicit specification of a shared conceptualisation</a>’… <a href=”http://www.ontopia.net/topicmaps/materials/tm-vs-thesauri.html#N773″>provid[ing] a shared vocabulary</a>, which can be used to model a domain… that is, the type of objects and/or concepts that exist, and their properties and relations’ — is a paradigmatic example of that very confusion.

What knowledge engineers mean is not ontology at all, but “epistemonomy” (although the credit for the coinage must alas go to <a href=”http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a739409602~db=all”>Foucault</a>).

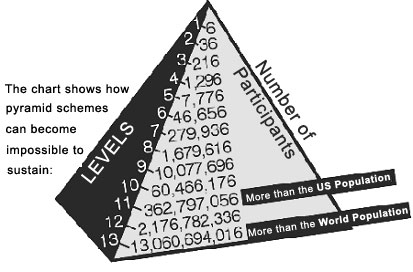

Isn’t Public Deficit Financing a Ponzi Pyramid?

Isn’t public deficit financing a Ponzi Pyramid, doomed to collapse sooner or later as surely as the Madoff meltdown? (Is Environmental Hedging not much the same thing?) Our species is reputed special for being uniquely able to “delay gratification” (short-term pain for long-term gain) — but with it seems to have come an appetite for the opposite: Short-term personal gain for others’ long-term pain.

Avatars: Virtual Life Began With The Word

![]()

All the fuss about the arrest of someone for electronic breaking-and-entering in order to off an avatar in an interactive virtual soap opera!

But virtual life really began with the birth of language itself — our transition from the “real” sensorimotor world to the symbolic world of verbal hearsay. With that, it was no longer just sticks and stones that could hurt us. The sensorimotor/symbolic boundary was permeable (hence no boundary) from the very outset. And not long thereafter, the pen became mightier than the sword, daggers drawn, ready to impose writ or dictum. Nor was there ever anything anaesthetic, anhedonic or anodyne about the world of words. People have been living affect-filled virtual lives through conversation, correspondence, and fiction for millennia (Cyrano de Bergerac, Misery Chastain, perhaps even Stephen Hawking are among its avatars). Even the Turing Test is predicated on it. Perhaps only our capacity for memory, imagery and “mind-reading” (via our mirror neurons) predate it.

On the Importance of Being Earnest

“… the kind of person that will patiently explain the facts of death to a child…”

— István Hesslein

The M.O.

Eszter Hagyatéka. A good portrait of a psychopath (con-man) and how their manipulative charm does not wear off even when their falseness and emptiness is transparent. The only thing that is not perfectly repulsive about them (for those who, unlike Eszter, are not otherwise in their thrall) is their almost touchingly naive conviction that everyone else is a psychopath too, “righteousness” being just another con. In this film, Lajos even effects to want to co-opt Eszter’s haplessly unvindictive righteousness to complement his own “insufficiently talented” M.O.

Eszter’s Lajos is unlike Mann’s Felix Krull, whose manipulative skills are grounded in a capacity for empathic mind-reading that is then used for exploitation. But there is still the same sense of an inescapable superficiality always yearning (but only, of course, superficially) for depth, while addicted only to the allures of the surface. Perhaps it’s a mistake to say that psychopaths have no feelings: They do, but they are faint and fleeting. They need to use method acting to simulate a soul — a soul that they know so well to be false, that they cannot conceive it to be otherwise in anyone else.

Richard Wagner

The Poet

is but an Oracle.

His ventriloquist Muse

channels through him,

via his Oeuvre,

not his Life

or his obloquy.

If a man chance

to be born taller than all others,

yea, let us have him

throw our Hoops.

But let us save our hoopla

for his opera omnia,

or his DNA,

not his Character.

Except he chance

to have one.

Onomastication

onomastication: having to eat your words (not to be confused with onomasturbation, which is (1) a form of “oral” sex (aka ononanism) as well as (2) a variety of logodaedaly, also known as onomancy)

On abstraction, definition, composition and symbol grounding in dictionaries

Re: Blondin Masse, A, G. Chicoisne, Y. Gargouri, S. Harnad, O. Picard, O. Marcotte (2008) How Is Meaning Grounded in Dictionary Definitions? TextGraphs-3 Workshop, 22nd International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Coling 2008, Manchester, 18-22 August, 2008

Many thanks to Peter Turney for his close and thoughtful reading of our paper on extracting the grounding kernel of a dictionary.

Peter raises 3 questions. Let me answer them in order of complexity, from the simplest to the most complex:

— PT: “(1) Is this paper accepted for Coling08?“

Yes. Apparently there are different sectors of the program, and this paper was accepted for the Textgraphs workshop, listed on the workshop webpage.

— PT: “(2) How come we claim the grounding kernel (GK) words are more concrete, whereas in our example, they are more abstract?”

The example was just a contrived one, designed only to illustrate the algorithm. It was not actually taken from a dictionary.

When we do the MRC correlations using the two actual dictionaries (LDOCE and CIDE), reduced to their GK by the algorithm, GK words turn out to be acquired at a younger age, more imagable, and (less consistently) more concrete and more frequent.

However, these are separate pairwise correlations. We have since extended the analysis to a third dictionary, WordNet, and found the same pairwise correlations, but when we put them together in a stepwise hierarchic multiple regression analysis, looking at the independent contributions of each factors, the biggest effect turns out to be age of acquisition (GK being acquired earlier), but then the residual correlation with concreteness reverses polarity: concreteness is positively correlated with earlier age of acquisition across all words in the MRC database, but once the GK correlation with age is partialled out, the remaining GK words tend to be more abstract!

This obviously needs more testing and confirmation, but if reliable, it has a plausible explanation: the GK words that are acquired earlier are more concrete, but the GK also contains a subset of abstract words, either learned later in life, or learned through early abstraction, and these early abstract words are also important for the compositional power of dictionary definitions in reaching other words through definition alone.

The next step would be begin to look at what those GK the GK words, concrete and abstract, actually are, and the extent to which they may tend to be unique and universal across dictionaries.

— PT: “(3) Does our analysis overlook the process of abstraction in its focus on acquiring meaning by composition (through dictionary definition)?”

Quite the contrary. We stress that word meanings must be grounded in prior sensorimotor learning, which is in fact the process of (senssorimotor) abstraction!

Peter writes: “we may understand ‘yellow’ as the abstraction of all of our experiences, verbal and perceptual, with yellow things (bananas, lemons, daffodils, etc.). When we are children, we build a vocabulary of increasingly abstract words through the process of abstraction.”

But we would agree with that completely! The crucial thing to note, however, is that abstraction, at least initially, is sensorimotor, not linguistic. We learn to categorize by abstracting, through trial and error experience and feedback, the invariant sensorimotor features (“affordances”) of the members of a category (e.g., banana, lemons, daffodils, and eventually also yellow), learning to distinguish the members from the nonmembers, based on what they look and feel like, and what we can and cannot do with them. Once we have acquired the category in this instrumental, sensorimotor way, because our brains have abstracted its sensorimotor invariants, then we can attach an arbitrary label to that category — “yellow” — and use it not only to refer to the category, but to define further categories compositionally (including, importantly, the definition through description of their invariants, once those have been named).

This is in agreement with Peter’s further point that “As that abstract vocabulary grows, we then have the words that we need to form compositions.”

And all of this is compatible with finding that although the GK is both acquired earlier and more concrete, overall, than the rest of our vocabulary, it also contains abstract words (possibly early abstract words, or words that are acquired later yet important for the GK).

— PT: “The process of abstraction takes us from concrete (bananas and lemons) to abstract (yellow). The process of composition takes us from abstract (yellow and fruit) to concrete (banana).“

The process of abstraction certainly takes us from concrete to abstract. (That’s what “abstract” means: selecting out some invariant property shared by many variable things.)

The process of “composition” does many things; among them it can define words. But composition can also describe things (including their invariant properties); composition also generates every expression of natural language other than isolated words, as well as every expression of formal languages such as logic, mathematics and computer programming.

A dictionary defines every word, from the most concrete to the most abstract. Being a definition, it is composite. But it can describe the rule for abstracting an invariant too. An extensional definition defines something by listing all (or enough of) its instances; an intentional definition defines something by stating (abstracting) the invariant property shared by all its instances.

— PT: “Dictionary definitions are largely based on composition; only rarely do they use abstraction.“

All definitions are compositional, because they are sentences. We have not taken an inventory (though we eventually will), but I suspect there are many different kinds of definitions, some intensional, some extensional, some defining more concrete things, some defining more abstract things — but all compositional.

— PT: “If these claims are both correct, then it follows that your grounding kernel words will tend to be more abstract than your higher-level words, due to the design of your algorithm. That is, your simple example dictionary is not a rare exception.”

The example dictionary, as I said, was just arbitrarily constructed.

Your first claim, about the directionality of abstraction, is certainly correct. Your second claim that all definitions are compositional is also correct.

Whether the words out of which all other words can be defined are necessarily more abstract than the rest of the words is an empirical hypothesis. Our data do not, in fact, support the hypothesis, because, as I said, the strongest correlate of being in the grounding kernel is being acquired at an earlier age — and that in turn is correlated, in the MRC corpus, with being more concrete. It is only after we partial out the correlation of the grounding kernel with age of acquisition (along with all the covariance that shares with concreteness) that the correlation with concreteness reverses sign. We still have to do the count, but the obvious implication is that the part of the grounding kernel that is correlated with age of acquisition is more concrete, and the part that is independent of age of acquisition is more abstract.

None of this is derived from or inherent in our arbitrary, artificial example, constructed purely to illustrate the algorithm. Nor is any of it necessarily true. It remains to see what the words in the grounding kernel turn out to be, whether they are unique and universal, and which ones are more concrete and which ones are more abstract.

(Nor, by the way, was it necessarily true that the words in the grounding kernel would prove to have been acquired earlier; but if that proves reliable, then it implies that a good number of them are likely to be more concrete.)

–– PT: “As I understand your reply, you are not disagreeing with my claims; instead, you are backing away from your own claim that the grounding kernel words will tend to be more concrete. But it seems to me that this is backing away from having a testable hypothesis.“

Actually, we are not backing away from anything. These results are fairly new. In the original text we reported the direct pairwise correlation between being in the grounding kernel and, respectively, age of acquisition, concreteness, imagability and frequency. All these pairwise correlations turned out to be positive. Since then we have extended the findings to WordNet (likewise all positive) and gone on to do do stepwise hierarchical multiple regression analysis, which reveals that age of acquisition is the strongest correlate, and, when it is partialled out, the sign of the correlation with concreteness reverses for the residual variance.

The hypothesis was that all these correlations would be positive, but we did not anticipate that removing age of acquisition would reverse the sign of the residual correlation. That is a data-driven finding (and we think it is both interesting, and compatible with the grounding hypothesis).

–– PT: “There is an intuitive appeal to the idea that grounding words are concrete words. How do you justify calling your kernel words “grounding” when they are a mix of concrete and abstract? What independent test of “groundingness” do we have, aside from the output of your algorithm?“

The criterion is and has always been: reachability of the rest of the lexicon from the grounding kernel alone. That was why we first chose to analyze the LDOCE and CIDE dictionaries: Because they each allegedly had a “control vocabulary,” out of which all the rest of the words were defined. Unfortunately, neither dictionary proved to be consistent in ensuring that all the other words were defined out of the control vocabulary (including the control vocabulary), so that is why Alexandre Blondin-Massé designed our algorithm.

The definition of symbol grounding preceded these dictionary analyses, and it was not at all a certainty that the “grounding kernel” of the dictionary would turn out to be the words we learn earliest, nor that it would be more concrete or abstract than the rest of the words. That too was an empirical outcome (and much work remains to be done before we know how reliable and general it is, and what the blend of abstract and concrete turns out to be).

I would add that “abstract” is a matter of degree, and no word — not even a proper name — is “non-abstract,” just more or less abstract. In naming objects, events, actions, states and properties, we necessarily abstract from the particular instances — in time and space and properties and experience — that make (for example) all bananas “bananas” and all lemons “lemons.” The same is true of what makes all yellows “yellows,” except that (inasmuch as vocabulary is hierarchical — which it is not, entirely), “yellows” are more abstract than “bananas” (so are “fruit,” and so are “colors”).

(There are not still unresolved methodological and conceptual issues about how to sort words for degree of abstractness. Like others, we rely on human judgments, but what are those judgments really based on?)

(Nor are all the (content) words of a language ranged along a strict hierarchy of abstractness. Indeed, our overall goal is to determine the actual graphic structure of dictionary definition space, whatever it turns out to be, and to see whether some of its properties are reflected also in the mental lexicon, i.e., not only our mental vocabulary, but how word meanings are represented in our brains.)

— PT: “You suggest a variety of factors, including concreteness, imageability, and age of acquisition. You are now fitting a multilinear combination of these factors to the output of your algorithm. Of course, if you have enough factors, you can usually fit a multilinear model to your data. But this fitting is not the same as making a prediction and then seeing whether an experiment confirms the prediction.“

I am not at all confident that the grounding kernel, extracted by our algorithm, was bound to be positively correlated, pairwise, with age of acquisition, concreteness, imagability and frequency, but we predicted it would be. We did not predict the change in sign of the correlation in the multiple regression, but it seems an interesting, interpretable and promising result, worthy of further analysis.

— PT: “I am willing to make a testable prediction: If my claims (1) and (2) are true, then you should be able to modify your algorithm so that the kernel words are indeed more concrete. You just need to ‘turn around your operation’.“

I am not quite sure what you mean by “turn around your operation,” but we would be more than happy to test your prediction, once we understand it. Currently, the “operation” is just to systematically set aside words that can be reached (via definition) from other words, iteratively narrowing the other words to the grounding kernel that can only be reached from itself. This operation moves steadily inward. I am not sure what moving steadily outward would amount to: Would it be setting aside words that cannot be reached via definition? Would that not amount to a more awkward way of generating the same partition (grounding kernel vs. rest of dictionary)?

Please do correct me if I have misunderstood.