You can read about stories from people who have contributed to wine production.

‘Let the terroir speak’ AdV, DRC (Burgundy)

‘To produce AOC wines does not necessarily mean producing the wines that you like. Can we be more ambitious than our AOC?’ A.MC, Premeaux-Prissey (Burgundy).

‘We are right at the limit when you can grow grapes commercially’., T.S Sussex (UK).

‘This wine was sparkling, they did not like it, it did not correspond to their expectations in terms of the tastes of the AOC in this area. But you see I thought it was nice, you could drink it with a picnic on a nice summer’s day’. C.L, Hautes-Côtes (Burgundy).

‘Vitivinicultural terroir is a concept which refers to an area in which collective knowledge of the interactions between the identifiable physical and biological environment and applied vitivinicultural practices develops, providing distinctive characteristics for the products originating from this area. Terroir includes soil, topography, climate, landscape characteristics and biodiversity features. (Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin, resolution’ OIV-VITI 3332010, author’s italics).

‘We don’t have the legislation they have so we can adapt our new techniques and develop new ideas’. T.S Sussex (UK).

‘When you work hard and you aim at producing better wines, in one way or another it costs more, then you logically have to increase your prices and then your clientele changes as a result’. JL, Vosne-Romanee (Burgundy).

‘I believe in terroir. It’s important terroir! I have this site located in a car park near the airport and the site was previously a car industrial site and an aviation zone during the Second World War. Year after year, we have won international awards for these wines. T.S, Sussex (UK).

‘Engaging around the environment is to gather around this cause, support the development of ever more sustainable practices, draw more attention towards them, contribute to the overall picture each time a little more and in doing so, step by step transforming the world’ (Teil, Barrey, Floux and Hennion 2011: 297; my own translation).

Terroir as Worldviews-Stories

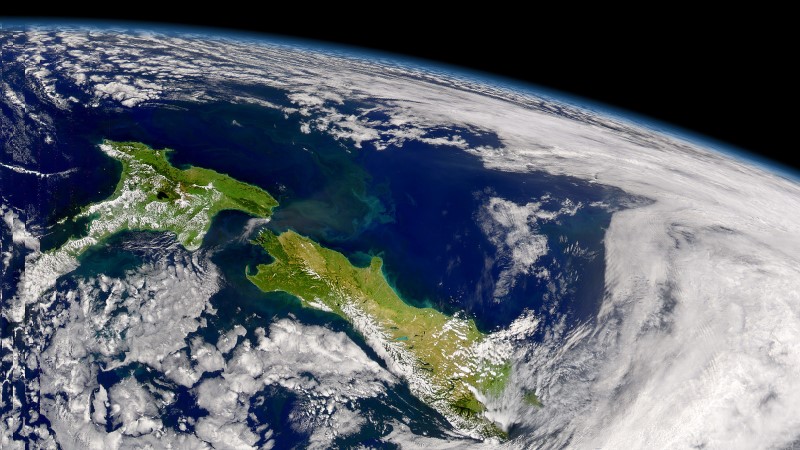

New Zealand

Nick Mills Pinot Noir 2017

Day 1, Session 2, Speaker 3

Karanga Mai! Mihi Mai! Thank you for your welcome.

My name is Nick

My Planet is Earth

My mountain is Tititea

My River is Mata-Au

My town is Wanaka

My farm is Rippon

My Iwi is Pakeha/Winegrower

My whanau is Mills

I am a product of my environment. In some respects, I’ve had little choice in the matter; I was born into Rippon, so talking about it has always come pretty naturally to me. Talking has always come pretty naturally to me.

Strangely though, preparing for this was really tricky. In searching out why, I came with the following thoughts:

The brief I’ve been given opens me up to consider pretty much most of what I know and love, so a greater sense of responsibility to do justice to all that, has fallen upon me.

Detailing to a few hundred of my peers how we are connected to our land, further binds us to our task: that is to hold on to our beautiful farm: to perpetuate certain pastoral values over successive generations of our family. To be honest though, I spend an unhealthy amount of time just terrified. Terrified of not being able to hold onto the farm and what that might mean to our family’s sense of self-esteem and definition. Talking about it here, in front of you all raises the stakes yet again.

But I’ve asked myself to be here, now, in the present, and not be limited by fear of the future.

I may talk about my place, but of course it doesn’t belong to me. I’m the second youngest of 6 siblings. I work with my mother, two of my sisters, my brother, my wife and about 5 full-time staff, some of them who have been with us over a decade. We have been granted a moment of custodianship over a very special piece of land, we care for collectively, but, over time each of us has developed our own unique relationships with it…

For me, I believe that landform, geology, geography, informs human culture as much as it does agriculture. Hang about long enough in one place and you become subject to the rhythms of that place.

But I’ve asked myself to be here, now, in the present, and not be limited by fear of the future.

I may talk about my place, but of course it doesn’t belong to me. I’m the second youngest of 6 siblings. I work with my mother, two of my sisters, my brother, my wife and about 5 full-time staff, some of them who have been with us over a decade. We have been granted a moment of custodianship over a very special piece of land, we care for collectively, but, over time each of us has developed our own unique relationships with it…

For me, I believe that landform, geology, geography, informs human culture as much as it does agriculture. Hang about long enough in one place and you become subject to the rhythms of that place.

So, I’ve been asked to speak about our place: how it was shaped and how it has shaped us. I’m going to do that following my mihimihi. But there’s a clear invitation here for you all, now and over the course of the next three days, to consider YOUR place and how THAT place has shaped you.

My Planet is Earth

I (and everyone else I know, all of us) live on a ball of molten rock that spins around in a vacuum. It’s just the right distance away from the Sun that water can exist in its all three of its forms: not so close so that it burns off into space, not so far away that it is bound up as a solid mass.

At some point, around one billion years into the earth’s existence, organic cells found a way to self-replicate…metabolising, eating, excreting, multiplying in a dark, wet and airless place.

Water became life.

Almost 2 billion years later (!), the first plants, trees, vines…evolved to put their roots down into this anaerobic mess and began to release vapour and gas and created the atmosphere.

This is perhaps Tane, Maori god of the forests tearing Ranginui, the sky father from Papatuanuku, the earth mother, to create the world

At any rate, the balanced, stable, self-regulating world that we can live in began here. And now, all life as we know it exists in this thin, receptive and fluid space between rock and nothingness.

My mountain is Tititea, Mount Aspiring

Over time, the earth developed a crust on the outside. It’s only about 1% of the planet’s volume (kind of like a skin of an apple), never the less it has become relatively rigid, broken only into large tectonic plates.

At some stage the Australasian plate and the Pacific plate began to collide, pushing land up out of the ocean and laying it into a massive chain of mountains that have become known as Kā Tiritiri o te Moana: The Southern Alps of New Zealand. Closest to us, and therefore the massif that most strongly guides our region’s climate is Tititea, the beautiful Mount Aspiring.

Nestled in under the eastern flanks of Aspiring is a place of temperance. A place of rest and education.

My town is Wanaka

Wanaka has the same root word as Wananga, which in our native language is school, or work shop. Maori used to come up from the strongholds on the East Coast and, while the men would cross the divide for in search of pounami (NZ’s greenstone), the families; the women and children would remain and teach/learn hunting, fishing, gathering, genealogy. Essentially how to survive.

Following the Te Puoho raid in 1836, Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, Wasteland’s Act 1855 a period of European land prospecting & pastoralism began. Now, over 100 years later, Wanaka is one of the fastest growing towns in the country, yet I believe these values of rest and education still exist. They remain instructive to the culture of our people and to the nature of our wines.

But I mentioned the word pastoralism. I’d like to talk about that idea and why it was so important to the development of our turangawaewae.

If farming is what one does on a piece of land; the period of pastoralism was more the seeking to find the potential of a piece of land, through any type of culture. Adapting one’s culture to the land and not vice versa.

My ancestors bought Wanaka Station, a large, isolated high-country run, in 1912. By necessity, the whole place was run by horses. Feed had to be grown for the horses. The local community was the permanent workforce on the farm; so food had to be grown to feed them. There were gardens, mixed crops, orchards, sheep, cattle, goats. Inventive ways of using water were developed for irrigation, grinding grain and electricity. It had a cook shop with a large bread oven and live in cooks that would feed the community. It was, in effect a self-sustaining farm unit.

This then, was the milieu that our father, Rolfe Mills was born into; and he spent a life time observing the land, particularly on the Rippon Hill part of the station and adapting the culture, including its viticulture, to it.

So, over time, on a farm on the shores of Lake Wanaka, through much trial and the odd error, the potential of a piece of land was found in wine growing.

My farm is Rippon Rippon is a very well defined piece of land; it’s a hill with steep slopes on all sides. Its vines lie on the north-facing slopes, but mixed crops, trees, animals, family areas and native habitat prosper on others. We farm Rippon as having its own identity.

When we talk about Rippon, we are talking about a distinct individual. It is our craft to maintain a culture, from micro through to macro, that maintains a relationship with this individual, and helps it to express itself as such.

This creates a notion of terroir that is perhaps more aligned with Steiner: A farm voice, which represents the living, breathing entity as the farm as a whole, rather than the Cistercian or Burgundian construct of a singular site, or climat, with which we are more familiar in pinot noir.

My whanau is Mills: Rolfe Mills, Lois Mills, my five siblings and their children, my wife Jo and our two boys

As a family, we’ve been on the land for over 100 years and we have subjected ourselves to the rhythms of this place. Above ground and within it.

The family house is made from earth. The earth was taken from the site. A hole was dug to make the cellar and then the earth is rammed into the walls. Timber was taken from the property for the trusses and internal structure. The kitchen cabinetry were once the kauri workshop benches from the Station’s old tractor shed.

This contributes to the feeling we have of having roots growing out of our feet and into our land.

And it reflects an understanding about wine: If one wishes their wines to be round, supple, alive, communicative of their soils, then when the wine is in its infancy, in the first 18 months of its life, when it is most receptive to its surrounds, then surely we must surround the wine in these elements. A vaulted cellar for example is round, supple, alive and reflective of its soils – it is in fact built out of them and through the barrels maintains a symbiosis with the young wine. A Georgian queveri has similar properties.

A rammed earth building, built from the land itself, had us growing up completely encased in our farms own native context.

So, that’s a start…

How else do WE (or how do we all) maintain a connection the land?

We feel we’ve been able to stay here, to gain our own purchase in this particular place, because of culture.

The emotional/spiritual base of this is love, family, team, community. The physical, or biological base starts with compost. This is a regular inoculation of living material, that grows down into the land and metabolises minerals out of the rock, into a form the vines can then gain their nutrition from.

These mature vines then, which are on their own roots, biodynamically grown and unirrigated, have now found true purchase in their place. They are in effect the living tissue, manifest of the land itself and as such, are a vital part of our turangawaewae.

The human link to our place begins the moment we’re born. The 5th generation on the farm has their placentas buried under the roots of native trees. Placenta and land share the same word in Maori: whenua. This strengthens the bonds between humans with their place of birth, enhancing their sense of belonging. The land on which these trees are planted faces the place where the ashes of their ancestors are kept.

As with any type of farming, trying to safeguard the relationship a family has with a piece of land, so that it might remain intact over successive generations, is the greatest and most rewarding challenge we face. This is particularly true in viticulture: the quality and accuracy of a wine depends on the health of the land and the vine, yet land and vines far outlive a single human generation. We can’t simply insist that our descendants carry on, they have to fall in love with the land on their own terms. They, like us, have to find out for themselves that it is something that might occupy and satisfy their passions over a life time. If winegrowing remains the clearest way of caring for the land, then learning the craft becomes a natural thing to do.

In the meantime, we as a family remain active participants in our greater environment. We lie, walk, swim, run, climb in it. We bring up our children as being part of it.

But engagement in land doesn’t always need to be active. It could be as simple as sitting, looking, listening.

One can also participate in the care of a place simply one’s purchase decisions (and consumption habits).

The engagement in a place could also be a form of reconciliation. Aiding the re-establishment of flora and fauna that was here before humans arrived, on our own land and public land alike.

This is a hand hoe! I’ve included it here as a totem representing an approach to team culture. As a team, we come to work ten minutes before actual start time for huddle. We shake each other’s hands, look each other in the eye, understand where each of us are all at and talk about what we’ve all got on for the day ahead.

We then get out into the vines and go hand hoeing: virtually every pair of hands on the property start their day on the kanuka handle of a heavy hand hoe. And in the dirt. We connect with our land, manually, on a daily basis.

We start each day as a collective, equally engaged in the same goal.

Our terroir is not just the soils, climate and vines, it’s us and how we communicate with each other.

It’s also how we share our culture with others: The Rippon Hall, also built from earth and wood from the property, is a place where our local community can be part of the culture of our land. Theatre, music, art, celebration, education, community groups…

Further afield this is also the base behind the Central Otago – Burgundy Exchange, now into its 11th year. And it’s from these encounters, we understand that we’re not alone or isolated in our work and values. And this is important.

While wine has developed certain geographic parameters over time: regions, appellations, particular sites (and the associated cartography that may help us to better identify their nuances), what we do and believe in as winegrowers has a clear universality.

Ultimately, I’m proud and completely comfortable being identified as coming from a distinct place. But as my mihimihi affirms, I identify this as simply being within a zone of crustal up-thrust that has come to be known as Rippon, Lake Wanaka, Central Otago, New Zealand.

I identify myself as being a part of this place, but my real peers aren’t just from here…they’re simply those who believe in the craft of the winegrower. That is, the development of living plant tissue from a particular site and guiding it through a natural secondary process into something we can taste, feel and assimilate into our own bodies. This doesn’t have political, national or even hemispheric boundaries. We’re on a ball! The equator is an arbitrary line on a map. Old World/New World what does that really mean anymore? Our craft is universal.

And I hope that this event and the conversations that follow can stand as testament to that: it is a celebration of pinot noir in 2017. It is held in New Zealand and has a certain directive towards promoting this country’s produce, but first and foremost it must be a celebration of our craft and the brilliant way in which it can make sense of time and place.

This sense of place exists on these Islands. It’s here now and from what we’ve just heard, it’s been here for some time. What’s left for you, is to go out from this room and find it. To feel it.

I’m immensely grateful to be have been given this opportunity to share, over the next few days, our place with you. I give my heartfelt thanks to all those who have made it possible.

Above all, I’m happy to be here. To share our time in wine, together.

We’re here now, let’s make the most of it! This is our iwi. Our tribe.For now, at least, this is our era.

Kia Ora!