Any social network potentially brings together groups with different perspectives and circumstances. ‘MeetingofMinds’ must take into account possible power dynamics between students and academics.

Models of PhD Supervision

There have been a number of attempts to model PhD supervision. More recently these have focused on supportive approaches allowing students to move from a state of relative dependency to complete independence (through a shift in the balance of control).

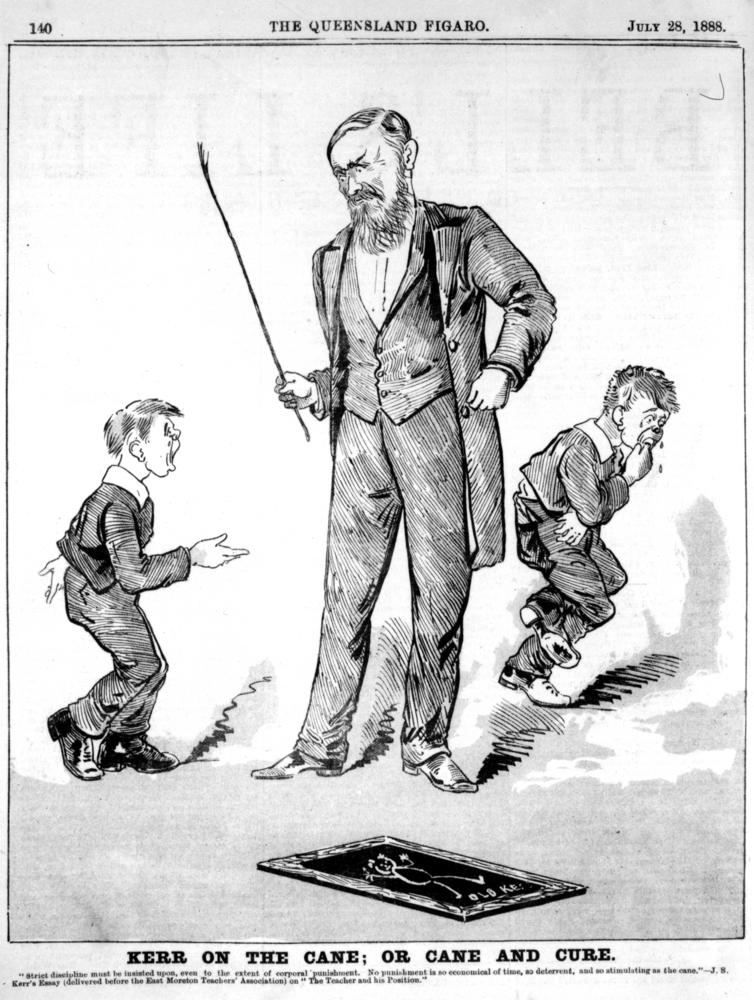

However there are also a number of potential power inequalities built into the relationship between supervisor and student. This includes:

- The supervisor is in a position of legitimate authority.

- They have perceived abilities to mediate rewards (e.g supporting publications) or punishments (e.g being unavailable for important meetings).

- A student may be influenced by the perceived expertise of the supervisor.

- Some students may be in awe of their supervisor, seeing them an example that they wish to live up to.

Photograph from Contributor(s): Queensland figaro – Copied and digitised from an image appearing in Queensland figaro, 28 July 1888, p. 140., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12662338

In comparison, the main legitimate power that the student has is that provided through university policy and complaints procedures. Many students, however, will be wary of using such instruments as they may be concerned of the impact on their long term relationship with their supervisor and the university.

Beyond formal power structures, there are other factors that might influence the relationship between student and supervisor.

It has been recognised that ‘the supervision relationship is infused with desire, fantasy, unresolved transferences, intimacy and power’ (Bastalich, 2015).

Some writers have also found that supervision can be tainted by the imposition of gender and cultural norms on the student. And there are risks that the power differential between supervisor and student could result in inappropriate behaviours. In a ‘survey of 1,839 current and former students by the National Union of Students (NUS) and campaigners the 1752 Group, 41% of respondents said they had faced unwelcome sexual advances and innuendo from university staff’ (Batty, 2018).

Such issues can lead to students dropping out of their degrees, at a time when demonstrating degree completion is becoming increasingly important to universities across the world.

Using ‘MeetingofMinds’ to Improve the Student-Supervisor Relationship

A recent meta-review has found that Web 2.0 tools have enabled greater dialogue and interaction between student and supervisor, including supporting the process research projects could be developed in a more collegial and collaborative way (Maor, Ensor, and Fraser, 2015)

Such tools are also important as increasing students work from a distance and so often have to communicate with supervisors via the Web.

Students who are uncomfortable with their supervisors, but do not wish to make a complaint, may also find this a preferable way to communicate.

It could also be useful for both student and supervisors to have archives of all their digital conversations, in the case of any tensions or disputes.

It is also important, however, to recognise that face to face interactions (both in terms of direct contact, but also through applications such as Skype) remain important between human beings for a number of reasons e.g the important of non-verbal gestures and expressions in human communication.

Other forms of power could emerge in an online environment. The student-supervisor relationship takes place in a fairly constrained ‘space’ (the university and academia) where news can potentially travel fast. A similar dynamic could take place in an online social network , for example an angry (well connected) student could send out information on their supervisor (via the network) which could be damaging to both of them.

Trust relationships in online social network can potentially be used to spread rumors and misinformation, and Chen et al (2015) found that students sometimes share misinformation on social media, often for non-informational reasons such as to share eye-catching messages or to interact with friends.

Research has found that viral content online tends to be surprising, emotionally complex, or extremely positive (Jones, Libert, and Tynski, 2016). In observational studies of information diffusion, it has been found that users may be influenced by friends to adopt information or share content, and because friends tend to be similar, anything tweeted by the users friends is more likely to be of interest to the user. Simple contagion models, however, have been challenged in a recent study. (Mønsted et al, 2017)

It will therefore be important for the site to be properly mediated, including clear rules and actions when these are not followed. As all users of ‘MeetingsofMinds’ will have university email addresses, allowing posts to be tracked back to source, and users could be banned from further use of the network. Other users of this network, who will be PhD students and academics, could also be asked to act as ‘guardians of the site’, and flag/report inappropriate postings.

By Nina Schuller

References

Bastalich, W (2015) ‘Content and context in knowledge production: a critical review of doctoral supervision literature’, Studies in Higher Education, 42 (7), pp 1145-1157, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1079702

Batty D (2018) ‘Sexual misconduct by UK university staff is rife, research finds’. The Guardian. 3 April, Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/03/sexual-misconduct-by-uk-university-staff-is-rife-research-finds (Accessed on the 4 April 2018)

Chen, X, Sin, S, J, Theng Y, and Lee, C, S (2015) ‘Why Students Share Misinformation on Social Media: Motivation, Gender, and Study-level Differences’. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 41 (5) pp 583-592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.07.003

French, J,R, P., and Raven, B (1959) ‘The bases of social power’. In D.Cartwright (ed.) Studies in Social Power. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Grove, J (2017) ‘PhDs: ‘toxic’ supervisors and ‘students from hell’. Time Higher Education. 7 April. Available at https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/phds-toxic-supervisors-and-students-from-hell (Accessed on the 4 April 2018)

Jones, K., Libert, K, and Tynski K (2016) ‘Combinations That Make Stories Go Viral’. Harvard Business Review. 23 May. Available from https://hbr.org/2016/05/research-the-link-between-feeling-in-control-and-viral-content (Accessed on 5 April 2018)

Kiley, M (2011) “Developments in Research Supervisor Training: Causes and Responses.” Studies in Higher Education, 36, pp 585–99. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.594595

Maor, D., Ensor, J, D and Fraser, B, J (2015) ‘Doctoral supervision in virtual spaces: A review of research of web-based tools to develop collaborative supervision’, Higher Education Research & Development, 35 (1), pp 172-188, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2015.1121206

Mønsted B, Sapieżyński P, Ferrara E, and Lehmann S (2017) ‘Evidence of complex contagion of information in social media: An experiment using Twitter bots’. PLoS ONE 12(9): e0184148. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184148

Orellana, M. L., Darder, A., Pérez, A., & Salinas, J. (2016). Improving doctoral success by matching PhD students with supervisors. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 11, pp 87-103. Available at http://ijds.org/Volume11/IJDSv11p087-103Orellana1629.pdf (Accessed on the 4 April 2018)