How Virtual Reality Revolutionises Filmmaking by Jonny Rogers

Where some have hoped virtual technology would enable us the ability to create for ourselves brand new worlds, others have worried that it would encourage us only to neglect our present one. Little thought, however, has been given to how virtual cinema has thus far best thrived; namely, in its ability to challenge and redefine the user’s relationship with the world. It is my view, in light of this, that virtual reality brings not only an exciting socio-technological revolution, but also a cinematic revolution forced to directly challenge certain conventions and expectations assumed by the contemporary traditional film industry (‘traditional’ meaning ‘non-virtual’ for the purpose of this article). The opportunities provided by virtual cinema facilitate great potential for greater personal and global change.

Figure 1. Frame from La sortie des usines Lumière (1895) (image from Grand Palais)

Before we look too far into the future of filmmaking, however, let’s have a little look at its past. For almost the first twenty years of cinema’s existence, ‘actualities’ dominated the first public scenes: films showing real events and every-day occurrences, such as the Lumière Brothers’ La sortie des usines Lumière (1895), featuring workers leaving a factory, and L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1896), featuring a train arriving at a station. Unlike documentaries, however, actualities were not structured or edited to form a larger argument or coherent picture, but instead celebrated the pure spectacle of seeing something being captured and reproduced through this new technology. This characterised an era of film history famously described by Tom Gunning as the ‘cinema of attraction’.[1] Although to modern audiences these early films might seem profoundly unremarkable, if often even laughable, a large proportion of popular virtual content appears to be essentially quite similar.

Figure 2. Frame from Mega Coaster: Get Ready for the Drop (2016) (image from YouTube)

The highest viewed non-licenced virtual reality video on YouTube, as of the time of this writing, with a total of over 34 million views, is Mega Coaster: Get Ready for the Drop, featuring, as the name suggests, a omnidirectional camera attached to a roller coaster.[2] Given the lack of given exposition, context or information, this film is in essence a contemporary ‘actuality’; its popularity is no doubt attributable to the novelty of the sensation it captures and reproduces. Other popular videos feature cameras mounted to aeroplanes,[3] surfboards,[4] skydivers[5] and wingsuits:[6] content which, though hardly absent in traditional platforms (especially on popular amateur streaming services such as YouTube), is rarely seen to be an exhibition of the medium’s potential (which is instead almost exclusively associated with the acting, directing, cinematography involved in a traditional film). Although the potential and future of virtual cinema is undoubtedly exciting, I have, perhaps most surprisingly, found that virtual reality has also helped me better understand, interpret and appreciate the emergence of traditional cinema nearly 130 years ago.

Figure 3. Frame from Evolution of Verse (2015) (image from Zach Richter)

Of course, connections and similarities to early and ‘silent’ cinema have been drawn already. Virtual reality filmmaker and entrepreneur Chris Milk even stated, at a TED talk discussing the birth of virtual reality an art form, “we are the equivalent of year one of cinema” as the aforementioned L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat is projected on the screen behind; [7] further alluding to this in his experimental work, Evolution of Verse (2015), which at the beginning features a train rapidly approaching the viewer before dissolving into countless birds. His talk ends with what claims to be the largest collective virtual viewing experience, as each member of the audience watches the same film (a series of scenes taken from various projects showing the potential of virtual filmmaking, beginning with this opening section of Evolution of Verse) through individual devices connected to a shared interface. As the train approaches, a growing hubbub quickly amounts into a brief period of screaming, which abruptly breaks into applause and laughter. The laughibility of the common-held myth that L’Arrivée d’un train sent its audience into a panicked frenzy is rendered silent here as virtual reality provides contemporary filmmaking a reenergised interest in the simple, formalistic, spectacle of seeing a new cinematic medium in action. The novelty of sensationalist virtual cinema might eventually fade into anecdotal mockery by future generations, but the history of cinema suggests that a decade or so of structural and aesthetic ‘simplicity’ could still lie ahead of us. Perhaps, furthermore, we could see a renewed academic or public interest in early cinema in this time.

Figure 4. Samsung’s 2017 Gear VR headset (image from CNET)

Unlike traditional cinema, however, virtual reality is, somewhat paradoxically, birthed through a reliance on both a more accessible and more individualistic platform: namely, mobile technology. As I started researching into virtual reality, I realised that this was not something I could access or experience for myself without a bigger or more powerful phone; it is no wonder that Samsung’s Gear VR, often now packaged with new mobile phones, dominates the virtual headset market (most other headsets of similar quality are more expensive and require powerful gaming systems or computers, and are as such better suited for gaming content). Although a VR-exclusive cinema does exist in Amsterdam,[8] which has expanded more recently to China, Finland and Romania, cinematic virtual content is predominantly produced for mobile platforms. It could hardly be expected that specified locations and services (unless virtual technology is integrated into existing cinemas) could support the establishment, expansion, and exploration of the medium when mobile platforms provide an immediate, universally accessible – and predominantly free – distribution service. From the fact that every filmmaker and production company, professional or amateur, is essentially forced to release content through these same limited services (such as Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Google Play or Oculus Video), this means a considerably small number of organisations are given complete control over almost all systems of distribution. Perhaps this will put more pressure on film festivals and technological or creative conventions to exhibit the more professional, or even nationalistic, end of original content.

One potential consequence of relying on mobile technology is that this might force a cultural homogenization of content: the predominant internationality of the Internet could make it more difficult to restrict the distribution of virtual films to specific areas, countries, and demographics. It is, however, perhaps too early to decide whether this will either serve or hinder production and exploration: many artistic revolutions in traditional cinema emerged from domestic movements, which were no doubt informed by the control of international distribution as informed by various political events and international relations. However, where the exhibition of traditional films originated in public spaces and then extended to more private markets through VHS, DVDs, Blu-ray and, more recently, online streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime, virtual reality is instead born through mobile technology, and attempts have been made to see its utilisation in public or communal spaces in the future. This shows that the growth of virtual reality almost inversely parallels traditional cinema, implying that the history of traditional cinema might not directly inform the future of virtual content as may first be assumed. Although virtual reality may be in part informed by what has come before, it has in some ways its own future to write: the immediate accessibility and intimacy of virtual content provides a considerably unique paradigm for the birth of a new artistic and creative platform.

Figure 5. Frame from MIYUBI (2017) (image from The Verge)

Where frequent editing is so commonplace in popular traditional cinema that it often even goes unnoticed, any cut between two shots in virtual reality is forced to be reserved almost exclusively for significant changes in time or location in the narrative. It would naturally appear quite jarring for the camera to, for example, frequently alternate between two or three different positions in a conversation, especially if such should involve significant head movement for the viewer; the virtual camera is not solely a means of seeing a location, but also creating the impression of being there. Although there are some virtual films which do more frequently cut between different positions, with Rose Colored (Adam Cosco, 2016), for example, jumping between the perspectives of two people in a bar in one scene, and at other points rapidly flicking through her memories, minimal editing still dominates the professional end of virtual cinema. Perhaps the most impressive long-form fiction narrative produced so far, MIYUBI (Felix Lajeunessse, Paul Raphael, 2017), which puts the viewer in the body of a toy robot given to, played with and eventually rejected by a young boy in the 1980s, at a length of 40 minutes, is composed of 11 different scenes, each featuring a single shot and minimal camera movement. Other well-acclaimed scripted shorts, such as The Invisible Man (Hugo Keijzer, 2016) and Henry (Ramiro Lopez Dau, 2015), likewise each feature both a continuous unbroken take and little-to-no camera movement.

Figure 6. Frame from Henry (2015) (image from VRScout)

The significance of these changes lie in the fact that, at a time in which popular films are becoming increasingly fast-paced and, as some filmgoers are arguing, too illegible for comfort, virtual reality cinema, by virtue of its own structural limitations, is forced to take a step back and reconsider its form and structure. An informal, but notable, report by film editor Vashi Nedomansky suggests action films and blockbusters often now average around 2 seconds per shot,[9] and critics and bloggers are taking to the internet to voice their concern for this trend:[10],[11] Simon Brew, the founder and Editor-In-Chief of Den of Geek, published an open letter to Hollywood to raise attention to how this could impact the accepted quality of storytelling.[12] The question now arises, however: could virtual reality encourage, let alone even demand, a significant trend toward minimalism?

Figure 7. The set of The Invisible Man (2016) (image from VR Reviews)

Considering the fact that nothing can be hidden ‘behind’ the camera, nor ‘out of shot’, the use of naturalistic lighting, on-location filming, and the absence of a crew all seem to be pragmatic obligations, meaning such techniques – often explored more in arthouse or independent productions – are brought to the forefront of a new cinematic revolution. The framing of the shot now involves consideration of all directions and dimensions, and hence the awareness that everything on camera could be seen, even if not directly relevant to the narrative. To discourage motion sickness, Samsung encourage that users use the technology for no longer than twenty minutes at a time, thus seemingly encouraging limitations on the length of films. As someone who tends to prefer these more short-form minimalistic, naturalistic and observational shades of traditional cinema anyway – favouring natural lighting, long takes, minimal editing, etc. – I am quite excited to see what virtual platforms will produce, and now with greater attention given by the growing public interest in the technology.

Figure 8. Entrepreneur and filmmaker Chris Milk delivers a TED talk (image from TED.com)

I am not saying that maximalism – rapid editing, high action or large budgets, etc. – necessarily makes for any inferior a form or quality of story-telling, with Mad Max: Fury Road, for example, having an average shot length of 2.1 seconds, surpassing all critical and financial expectations, but rather that virtual cinema embraces, and hence reenergises, cinema’s potential for capturing the simple, the subtle and, often, the slow. As Chris Milk (whose production company, Here Be Dragons, undoubtedly stands above the rest with regards to quality of content) says, “we are more learning grammar than writing language” at this stage of the game.[13] It will as such have to be a new generation of filmmakers that will find, explore and break the rules of virtual story-telling; there is no guarantee that the skills encouraged in traditional filmmaking will translate to the production of virtual content. Attempts to replicate Hollywood approaches to action sequences in virtual reality often, in my view, reveal only their silliness: the medium, as with any artistic platform, best thrives when it understands and uses its own limitations.

Figure 9. BeAnotherLab exhibiting their technology in the Tribeca Film Festival (image from Tribeca Film)

Although I cannot quite pinpoint my first point of contact with the idea of publically accessible virtual reality, I no doubt came to be aware of it through the general public focus on its use in gaming, but perhaps my first awareness of its cinematic potential came when I stumbled across BeAnotherLab’s early experimental work about five years ago. Their central project, The Machine to Be Another, focuses on the integration of cameras into virtual headsets to allow two individuals – either two participants or a participant and a performance artist – to see the world from the other’s perspective.[14] Either the performance artist will imitate the actions of the participant or both participants will imitate each other as two staff simultaneously touch parts of both individuals’ bodies to stimulate each user to identify with their virtual body. Scientific research, their website claims, has shown that inducing such a perceptual illusion has “great potential in reducing implicit racial bias and promoting altruism”.[15] Their technology is used for, though not limited to, artistic performances and installations, physical and psychological rehabilitation services, and the resolution of personal conflicts (marital, racial, sexual, etc.). This provides an intimate connection with the image otherwise unparalleled by previous cinematic mediums.

Figure 10. Clouds Over Sidra (2015) is shown at the World Economic Forum in Davos (image from Creators Vice)

Although this specific project involves a degree of immersion and performance that some might feel renders it extra-cinematic, the essentially empathetic and educational nature of virtual reality has been more recently brought into public spheres. Perhaps most significantly, Chris Milk worked with Gabo Arora, a Creative Director and Senior Advisor at the United Nations, to produce a series of 3D virtual documentaries directly aimed at promoting particular social causes.[16] One of their films, Clouds Over Sidra (2015), featuring a twelve-year-old Syrian girl guiding us through her day-to-day life in a refugee camp in Jordan, was shown at the World Economic Forum in Davos to a group of influential politicians, economists and journalists whose decisions affect the lives of millions of people such as those shown in the film: people, Milk says, who “might not otherwise be sitting in a refugee camp in Jordan”.[17] The central supposition here is that virtual reality provides a means not just to see a girl in a refugee camp “through a window”, but rather to be “there with her”; when you look at the floor, Milk notes, “you’re sitting on the same ground that she’s sitting on”. This is, of course, where virtual reality most significantly moves away from its affinity to early actuality cinema, instead utilising its sensationalist potential as a platform for social and political discussion; and this is where I think virtual cinema proves to be most exciting.

Figure 11. Frame from Waves of Grace (2015) (image from Here Be Dragons)

I think people are both interested in and scared of virtual reality for the same reason: the possibility that it could provide some addictive means of escaping reality – this idea essentially serves the plot of The Matrix (Lana Wachowski, Lilly Watchowski, 1999), Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995), and the upcoming Ready Player One (Steven Spielberg, 2018) – but rest assured, where the medium excels is where it allows people to experience something more of reality: where it allows you to meet – and sometimes even become – other people to experience something of their lives and how they experience the world. A particular favourite film of mine, Waves of Grace (Chris Milk, Gabo Arora, 2015), tells the story of an Ebola survivor who uses her immunity to the disease to work with other victims as she narrates us through a prayer: I could not help but feel a tear come to my eye as children surrounded me in an abandoned swimming pool. It might seem quite ambitious for Milk to claim virtual reality allows one to experience “humanity in a deeper way”, [18] but such an experience cannot be justified without first trying for oneself.

Far from distracting from reality, virtual content shows a focus on utilising the inherent connectivity and sociability of mobile platforms to aid in public education and discussion. Other significant films, for example, show attempts to induce the experience of being an autistic child,[19] a man losing his sight, seeing the world through the eyes of animals and standing inside otherwise inaccessible locations such as the centre of CERN’s Large Hadron Collider[20] or public celebrations in North Korea.[21]

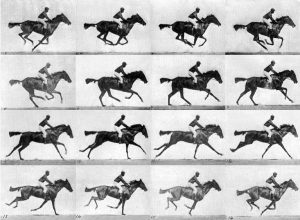

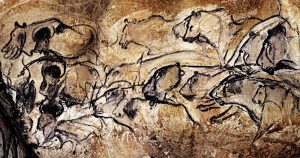

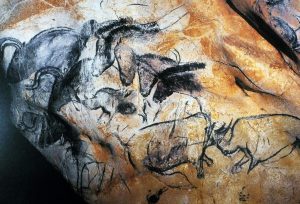

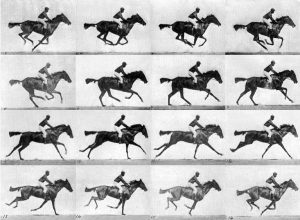

Figure 12. The Horse in Motion (1878), photographed by Eadweard Muybridge (image from Equine Ink)

Although animal life has been captured on film since its pre-natal stage in Eadweard Muybridge’s experiments in motion photography, through which he attempted to reveal the movement of a horse through printing successive frames of motion, virtual reality means that life can finally be experienced through film. A high-end quality 3D virtual production company, Condition One, advertises its award-winning In The Presence of Animals (2016) as a unique encounter with nature, “from inside”, “alongside” and “amid” various groups of endangered animals.[22] The existential experience of feeling the presence of animal life through a virtual film is, at least to me, unparalleled by any traditional counterpart. Other nature and scientific research organisations, such as the National Geographic Society and Discovery have also quickly taken to the production of virtual content, using their wealth of experience and established reputation to produce more exotic and exciting virtual films: encounters with hammerhead sharks[23] and lions,[24] and views of outer space[25] and shipwrecks[26] frequently dominate the ‘featured content’ pages on streaming platforms.

Figure 13. Frame from Operation Deathstar (2017) (image from YouTube)

Many of these virtual nature documentaries also attempt to utilise both the opportunities provided by and the excitement surrounding the medium as a platform for the discussion of wider ecological, environmental and ethical issues: even non-profit charitable organisations are producing virtual-specific content to raise awareness for their cause, such as The Nature Conservancy, who through This is Our Future (2017) attempt to show the dangers of overexploitation of the world’s fish stocks. Two films I have found particularly fascinating, Operation Deathstar (Danfung Dennis, 2017) and Operation Aspen (Danfung Dennis, 2017), show attempts by the animal rights activist group Direct Action Everywhere to break into, respectively, pig and chicken factory farms to rescue animals from their subjugation to illegal practises and objectionable conditions. The experience of not merely seeing but feeling the presence of these animals, knowing also the likelihood of their death by the time of your watching, is an undoubtedly haunting experience for many; it may not be too long before virtual production companies produce their own Earthlings (Shaun Monson, 2005) or Blackfish (Gabriela Cowperthwaite, 2013) to shock and horrify its audience into personal, industrial and political change. The limitations of virtual reality as mentioned earlier – the consideration of motion-sickness, minimalism of editing, etc. – combined with the investment of environmental organisations looking to reach a mass audience, have no doubt facilitated the relatively quick production of these more professional short-form documentaries.

In conclusion, the fact that virtual reality is forced to challenge certain structural and aesthetic conventions assumed by the traditional industry, hence celebrating more naturalistic and minimalistic approaches to filmmaking, provides a framework to better understand early cinematic history, reenergises an interest in the pure sensation of watching and experiencing, is almost exclusively dependant on mobile access to predominantly international online streaming services, and has already been supported by individuals with various ecological, scientific, religious, political, social and educational agendas, I believe it can be safely asserted that virtual reality is – if there was ever any doubt – more than a novel technological experience. More essentially, it provides a cinematic revolution of a magnitude and potential comparable even to the transition of photography to film: photography built on the plastic arts by reproducing light and shadow in a specific area and cinema built on photography by recording and projecting the movement of light and shadow, but now, with virtual reality, the camera is finally able to capture more than any individual can see. Virtual reality reminds us that the world is far bigger and far more exciting than we could ever imagine alone.

FILMOGRAPHY:

Blackfish. Gabriela Cowperthwaite. CNN Films, Manny O. Productions, Magnolia Pictures. United States. 2013

Clouds Over Sidra. Gabo Arora, Barry Pousman. VRSE.works. 2015

Earthlings. Shaun Monson. Nation Earth. United States. 2005

Evolution of Verse. Chris Milk. Annapurna Pictures, Digital Domain, VRSE.works. United States. 2015

Henry. Ramiro Lopez Dau. Occulus Story Studio. United States. 2015

In the Eyes of the Animal. Abandon Normal Devices, Forest Art Works, Forestry Commision England, Marshmallow Laser Feast, The Space. United Kingdom. 2016.

L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat / The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station. Auguste Lumière, Louis Lumière. Société Lumière. 1896

La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon / Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory in Lyon. Louis Lumière. 1895

Mad Max: Fury Road. George Miller. Kenney Miller Mitchell, RatPac-Dune Entertainment, Village Roadshow Pictures, Warner Bros. Pictures. Australia, United States. 2015.

MIYUBI. Felix Lajeunessse, Paul Raphael. Felix & Paul Studios, Occulus, Funny or Die. United States. 2017

Notes on Blindness: Into Darkness. Archer’s Mark, ARTE France, AudioGamig, Ex Nihilo. 2016

Operation Aspen. Danfung Dennis. Condition One, Direct Action Everywhere. United States. 2017.

Operation Deathstar. Danfung Dennis. Condition One, Direct Action Everywhere. United States. 2017.

Ready Player One. Steven Spielberg. Amblin Entertainment, Amblin Partners, De Line Pictures, Fara Films & Management, Village Roadshow Pictures, Warner Bros. United States. 2018

Rose Colored. Adam Cosco. Invar Studios. United States. 2016

Strange Days. Kathryn Bigelow. 20th Century Fox, Universal Pictures, Lightstorm Entertainment. United States. 1995

The Invisible Man. Hugo Keijzer. Midnight Pictures, The Secret Lab. United States. 2016

The Matrix. Lana Wachowski, Lilly Watchowski. Groucho II Film Partnership, Silver Pictures, Village Roadshow Pictures, Warner Bros., Roadshow Entertainment. Australia, United States. 1999

Waves of Grace. Gabo Arora, Chris Milk. VRSE.works. United States. 2015

[1] Tom Gunning, ‘The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, Wide Angle, 8 (3-4), 1986.

[2] Discovery, Mega Coaster: Get Ready for the Drop (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-xNN-bJQ4vI [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[3] Blick, 360° cockpit view / Fighter Jet / Patrouille Suisse (YouTube, 2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NdZ02-Qenso [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[4] World Surf League, Get Barreled in Tahiti with C.J. Hobgood & Samsung Gear VR 360 (YouTube, 2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7gjR60TSn8Q [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[5] vr360 pro, SkyDive in 360° Virtual Reality via GoPro (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S5XXsRuMPIU [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[6] Making View AS, Wingsuit 360° Experience (YouTube, 2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t99N223fqCo [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[7] TED, The birth of virtual reality as an art form (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cJg_tPB0Nu0 [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[8] Raymond Wong, ‘World’s first permanent VR cinema opens in Amsterdam, and it’s very weird’, Mashable (2016). Available at: http://mashable.com/2016/03/07/vr-cinema-amsterdam/#wGcuq0Tk9gqD [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[9] Vashi Nedomansky, ‘The Fastest Cut: Furious Film Editing’, Vashi Visuals (2016). Available at: http://vashivisuals.com/the-fastest_cut/ [Accessed 27th August 2017].

[10] Anne Billson, ‘Action sequences should stir, not just shake’, The Guardian (2008). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2008/nov/05/action-films-bad-editing [Accessed 8th September 2017]

[11] Graham Winfrey, ‘’Kong: Skull Island’ Scene Slammed for Insanely Fast Editing – Watch’, IndieWire (2017). Available at: http://www.indiewire.com/2017/06/kong-skull-island-criticized-fast-editing-jordan-vogt-roberts-watch-1201847583/ [Accessed 8th September 2017]

[12] Simon Brew, ‘An Open Letter To Action Movie Editors & Directors’, Den of Geek, (2008). Available at: http://www.denofgeek.com/movies/13811/an-open-letter-to-action-movie-editors-directors [Accessed 8th September 2017]

[13] TED, The birth of virtual reality as an art form (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cJg_tPB0Nu0 [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[14] The Verge, Using the Oculus Rift to enter the body of another (YouTube, 2014). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dOSJETowuik [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[15] ‘Library of Ourselves’, BeAnotherLab. Available at: http://beanotherlab.org [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[16] ‘Gabo Arora’, VR Days. Available at: http://vrdays.co/people/gabo-arora/ [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[17] TED, Chris Milk: How virtual reality can create the ultimate empathy machine (YouTube, 2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXHil1TPxvA&t=384s [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[18] TED, Chris Milk: How virtual reality can create the ultimate empathy machine (YouTube, 2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXHil1TPxvA&t=384s [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[19] The National Autistic Society, Autism TMI Virtual Reality Experience (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgDR_gYk_a8 [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[20] BBC News, Step inside the Large Hadron Collider (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_OeQxoKocU [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[21] ‘Enter North Korea’, CNN (2017). Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2017/04/25/vr/north-korea-pyongyang-kim-jong-un-celebration-vr/index.html [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[22] Condition One VR, In the Presence of Animals (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCtWo-yh3F4 [Accessed 27th August 2017]

[23] National Geographic, 360° Great Hammerhead Shark Encounter (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rG4jSz_2HDY [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[24] National Geographic, Lions 360° (YouTube, 2017). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sPyAQQklc1s&t=173s [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[25] Seeker VR, Journey To The Edge Of Space (YouTube, 2016). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCve1w1GFOs [Accessed 28th August 2017]

[26] Discovery VR, MythBusters: Sharks Everywhere! (YouTube, 2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WIS6N_9gjA [Accessed 28th August 2017]