The recent critical acclaim and commercial success of the video game Cuphead (2017) has not only drawn new attention to the 1920s and 1930s animated cartoons the game’s visual style is inspired by, but has also provoked new scrutiny of the ‘Racist spectre’ of the imagery it uses. By mimicking the style of animation seen in the work of the Disney and Fleischer studios, among others, the game also evokes racial caricatures based in both appearance and behaviour of characters. As Nicholas Sammond has discussed, American animated cartoons of that period were heavily derived from blackface minstrelsy traditions and relied on a number of racial stereotypes. How should we deal with old films like these, which reflect the values of their time but are today considered derogatory and offensive? For many fans, including the makers of Cuphead, the visual style and appeal of these cartoons can be separated from their social context and still enjoyed. For others these films must be condemned outright if progress and equality are to be achieved.

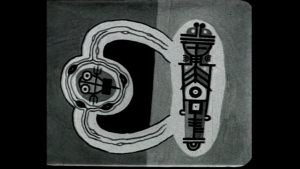

These debates affect not only popular mainstream cartoons, but also celebrated works of animation artists. In researching the work of Len Lye for a recent publication I found similar concerns arose. The New Zealand artist moved to London in the 1920s and produced a series of animated films, including some for the British Government funded General Post Office (GPO) film unit. His first film Tusalava (1929) draws on Lye’s experience of Maori art in his home country of New Zealand, Aboriginal art from Australia and his time in the South Pacific, when Lye may have had firsthand, though limited, exposure to indigenous arts in Samoa. As Figure 1 suggests, this could be considered an ‘appropriation’ of these other cultures by a white artist working in London.

Figure 1: Tusalava (Len Lye, 1929)

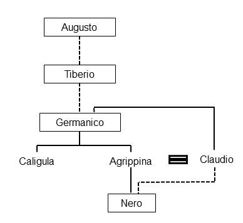

Lye’s second film, known as Experimental Animation or Peanut Vendor adopts a very different technique and style, but may also be considered to rely on derogatory stereotypes. In this 1933 film a stop-motion puppet of a monkey sings the popular jazz hit “The Peanut Vendor”. With his large, bulging eyes, protruding lips, gleaming teeth, enlarged hands and feet, and elongated limbs (see Figure 2), Lye’s monkey protagonist clearly shares similarities with the depiction of African-American stars in animated cartoons, and the carefree and flamboyant attitude he projects has both ethnic and class implications.

Figure 2: Experimental Animation (Len Lye, 1933)

While Lye’s later films became more visually abstract and abandoned this problematic imagery, his use of music derived from African-American and Latin jazz traditions suggests a continuation of the ‘primitivism’ of his earlier work. Lye’s most famous film, A Colour Box from 1935 was very widely seen thanks to its sponsorship from the GPO Film Unit. The film used experimental techniques of painting and scratching directly onto the film strip (see Figure 3) and was accompanied by ‘La Belle Créole’ by Don Baretto and His Cuban Orchestra.

Figure 3: A Colour Box (Len Lye, 1935)

Like Hollywood cartoons of the same period, critical reflection on Lye’s work becomes caught between celebrating their experimentalism and exuberance or condemning the films for their appropriations and stereotypes. Researching their use of jazz offers one way to navigate these binaries and move beyond them. This music was associated with the Harlem Renaissance, which might be understood as a primarily African-American movement, yet Caribbean artists, especially musicians, played an important role in it. For instance, ‘The Peanut Vendor’ started life as ‘El Manicero’ written by Moisés Simons, a Cuban musician of Basque descent, and became a popular hit in Cuba in the 1920s. Don Azpiazú and his Havana Casino Orchestra travelled from Cuba to New York in 1930 and presented the song successfully in its original Spanish language, but the song achieved lasting success when translated into English. It became something of a craze (it was the ‘Gangnam Style’ of its day with an associated dance!) and was recorded by numerous Harlem musical stars, including African-Americans Louis Armstrong in 1930 and Duke Ellington in 1931, as well as the white jazz bandleader Red Nichols, who produced the recording used by Lye.

Born out of a colonial melding of African and Spanish cultures due to the circumstances of the slave trade in the Caribbean, transported to New York where it was absorbed into a primarily African-American movement and Anglicised before becoming a part of widespread American popular culture and then exported internationally, ‘The Peanut Vendor’, and Latin jazz generally, were thus products of a complex international gestation, just like Lye himself. Lye was a white colonial subject, having been born in 1901 when New Zealand was still a colony, before it became a Dominion in 1907. He subsequently lived in Samoa and Australia, before arriving in London. While we may feel uneasy about aspects of Lye’s appropriation of other cultures, we might also see strong parallels in these complex histories, which challenge any easy notion of cultural specificity or authenticity in which an art work wholly and unequivocally expresses the single culture it derives from. Neither Lye’s work nor the jazz it incorporates can be considered to meet such a standard.

As well as adding new insight into Lye’s own work, this approach also suggests a way to negotiate other problematic works of the past. Through detailed research we can fully acknowledge the values of the time that underpin them, recognising their derogatory and offensive implications, while also appreciating the complexities and nuances involved, rather than relying on simplistic binary judgements.

Malcolm Cook’s chapter ‘A Primitivism of the Senses: The Role of Music in Len Lye’s Experimental Animation’ appears in Holly Rogers and Jeremy Barham (eds) The Music and Sound of Experimental Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017)