The thick waft of buttered popcorn; the over-sized cupholder stuffed with empty sweet packages; the stale soft-drink puddles you can’t avoid stepping in – and who can forget that endless chorus of chewing and slurping?

The consumption of food and beverages are, to say the least, heavily embedded in the cinema-going experience – yet this is seldom acknowledged by film critics and theorists. In Anne Bower’s 22-chapter Reel Food (2012), which explores how acts of consumption are involved in constructing national, political and sexual identities through film, only one chapter is devoted to the exploration of food as an essential aspect of the cinema-viewing experience. And yet, as writer James Lyons observes, the consumption of food is one of the most important means by which audiences “embellish and enhance the experience of film watching” – and, perhaps above all else, a crucial source of income for exhibitors.

In this post, I aim to survey how a careful consideration of the relationship between acts of consumption and cinema might challenge the prevailing theoretical assumptions in the study of film aesthetics, history and politics.

Food in Film Criticism

First of all, it is worth noting that our ordinary critical language typically associates food with cinema as a ‘low-brow’ or ‘escapist’ medium. The terms ‘brain candy’, ‘visual feast’ and ‘popcorn film’, for example, are used to dismiss films that do not warrant much serious reflection, not least academic attention. In perhaps one of the earliest critical uses of the term, The Daily Times described Venom (1982) as a “spine-tingling brain candy” to complement its value as an artefact of entertainment while admitting to the suspension of disbelief required to swallow its premise.

The prevalence of these food idioms in our casual critical language allows viewers to create an ‘ironic’ detachment that justifies the enjoyment of a film they didn’t take too seriously. Like the junk food they reference, popular cinema is situated as an essentially harmless hedonic and sensory experience, as opposed to a strictly rational or intellectual one. This discourse, as I shall further explore, likely finds it origins in early film theory and exhibition.

Concessions and Class in Early Cinema

Throughout its history, the film industry has long tried to legitimate itself as an artistic and culturally-valuable medium, often adopting conventions and practises from the more established disciplines of literature, fine art and theatre. From the early 20th century, many film exhibition venues in major cities across the world were designed to resemble opera houses and theatres, and further attempted to draw upon associations with the ‘upper-class’ spaces and institutions of continental Europe from the preceding centuries.

In the 1913 program for the New Gallery Kinema in London’s Regent Square, for example, imported beers and afternoon teas were advertised to wealthy patrons, while the June 1934 program for Edinburgh’s New Picture House drew attention to the four-course lunch, smoke room and dining halls available in the venue. The consumption of certain foods and beverages hence elevated cinema into a higher cultural domain, emboldening the growing industry with more ‘genteel’ food rituals and symbolism.

On the other hand, early theatres in the United States typically distanced themselves from the association of public eating spaces with the more ‘profane’ carnival and burlesque industries. The admission of confectionery could risk spoiling the cinema’s theatrical rugs and carpets, and, more notably prior to the advent of sound cinema in 1927, would distract the audience away from the screen – and, worse yet, disturb the wealthier patrons.

Nevertheless, as the film industry began to trade intertitles for dialogue, literacy no longer provided a barrier for working class audiences, while the Great Depression brought even greater interest in cheap entertainment and distraction. Cinemas slowly give up their former high cultural aspirations when they realised that they would yield greater profit from opening up to wider audiences. Although food vendors rented spaces in or outside theatre lobbies during this time, theatre owners eventually decided to cut the middle man and include food consumption in their marketing and exhibition practises.

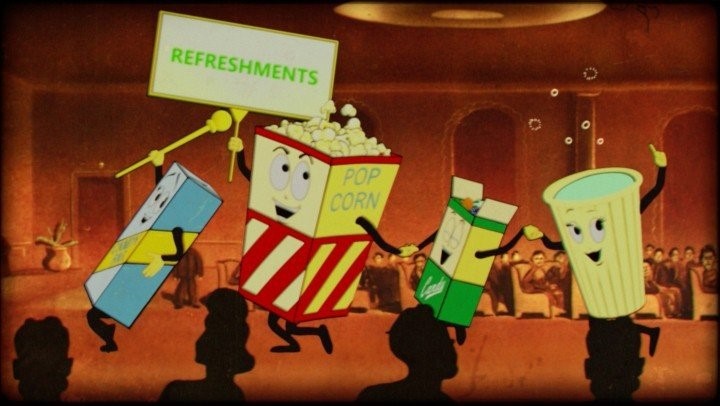

The Emergence of Popcorn

As wartime sugar and chocolate rationing provoked exhibitors to look for alternative sources of revenue, a perfect solution was discovered in popcorn. Contrary to the prior assumptions of film exhibitors, this would prove crucial to the survival of the cinema industry: a theatre chain in Dallas is said to have installed popcorn machines in all but their five ‘best’ theatres, only for those five to close within the following two years due to falling profits. Overseas servicemen brought popcorn around the world as a nostalgic ‘luxury’, making way for American popcorn manufacturers to break into European markets after the war – something that has never really changed to this day.

Although it is difficult to gather accurate data, Time magazine reported in 2009 that concessions make up to 20% of a film theatre’s revenue and 40% of its profits in the United States, since a large proportion of ticket sales goes back to the film studios, as well as funding staff costs and theatre maintenance. This data is loosely confirmed by private research and interviews with theatre owners, though some factors will inevitably vary in different locations – popcorn itself can gather 85-90% profit for every unit sold, with added salt motivating the additional purchase of soft-drinks.

This provides an unexpected incentive: films with uncomplicated plots and narrative structure might actually yield proportionately greater profit for film theatres, even despite lower admission prices, as the audience are more likely willing to leave their seats to buy more food mid-way through the film – this no doubt goes some way as to explain why, as explored previously, food vocabulary is utilised in modern film criticism as such. Regardless, as Epstein has concluded cinema theatres are as much in the fast-food and advertisement industries as film distribution – a thought that might greatly disturb prevailing theoretical understanding of cinema.

Food for ‘Alternative’ Markets

Although popcorn and fast food quickly became deeply embedded in the cinema experience after WWII, its absence was – and continues to be – offered as a hallmark of sophistication and originality. Post-war arthouse and independent cinemas across Europe and the United States began offering pastries and coffees in smaller, café-styled venues, as an alternative to the more infantile associations of sweets and refined sugar. As Lyons observes, popcorn in particular has remained “a peculiarly emblematic commodity” in the mobilization of cultural distinctions throughout cinema history; a totem for the ‘escapist’ associations that film exhibitors either attempt to capitalise on or distance themselves from. Today, individual cinema chains and film festivals continue to privately reconstruct cinema experiences through providing alternative and unique food-screen paradigms: the British Everyman cinemas, for example, claim that they are “redefining cinema” by swapping soft drinks for red wine and pizza in their “innovative lifestyle approach” to film exhibition, and the States-based Film Food Festival helps its audiences simultaneously taste what they see on the screen. These theatres and programmes, and others like them, thereby depend on the discourses associations that encourage the denigration of popular cinema as ‘junk’ entertainment to differentiate their services as unique, ‘event’-oriented experiences.

On the other hand, the Planet Hollywood chain and its countless imitators somewhat invert this process, embellishing the family restaurant experience with mounted props, signatures and iconography from cinema history. Although this perhaps strays too far from my focus on film exhibition, it is no small matter that entire businesses are modelled on the premise that cinematic artefacts, sanctified by their participation in popular culture, can somehow enhance, or otherwise transform, the more profane activity of food consumption.

Conclusion

If it is true that acts of consumption are heavily involved in how films are experienced, distributed, assessed and situated in particular socio-political contexts, then it appears that cinema cannot be simply described as a matter of sight and sound (sorry, BFI!); but also, of smell, touch and taste –far from compromising its integrity, however, I would argue that this privileges cinema with comparatively unique opportunities as an immersive and engaging public institution. Much might be said on this topic, of course, but I intend here to provide – if you forgive the pun – an appetiser for further research.

Research

‘About Everyman’, everymancinema.com. Available at: https://www.everymancinema.com/about-everyman

‘About the Food Film Festival’, thefoodfilmfestival.com. Available at: https://www.thefoodfilmfestival.com/the-festival

Avery, T., ‘Popcorn: A “Pop” History’, pbs.com, 2013. Available at: http://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/popcorn-history/

Bower, A. L., ‘Watching Food: The Production of Food, Film and Values’, Reel Food: Essays on Food and Film (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 1-13.

Butler, S., ‘A History of Popcorn’, History.com, 2018. Available at: https://www.history.com/news/a-history-of-popcorn

‘Capsule Reviews’, Daily Times, 1982, p.16.

Epstein, E. J., ‘The Popcorn Palace Economy’, Slate, 2006. Available at: https://slate.com/culture/2006/01/the-thirsty-moviegoer-fuels-the-movie-business.html

Geiling, N., ‘Why Do We Eat Popcorn at the Movies?’, Smithsonian.com, 2013. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/why-do-we-eat-popcorn-at-the-movies-475063/

Lobb, A, ‘Why does that popcorn cost so much?’ CNNMoney, 2002. Available at: https://money.cnn.com/2002/03/08/smbusiness/q_movies/

Lyons, J., ‘What about the Popcorn? Food and the Film-Watching Experience?’, in Bower, A. L. (ed.), Reel Food: Essays on Food and Film (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 311-333.

Tuttle, B., ‘Movie Theatres Make 85% Profit at Concession Stands’, Time, 2009. Available at: http://business.time.com/2009/12/07/movie-theaters-make-85-profit-at-concession-stands/