One of the aims of film scholarship is to understand how films ‘work’ – that is to say, how the different elements we see and hear on screen make us happy, sad, scared, relaxed, enlightened, confused, and so on. Yet few film scholars speak to actual audiences about how they make sense of the films they watch.

This is partly because audience research can be expensive and time-consuming to conduct. Working with human participants also requires a high level of ethics clearance, along with lots of paper work, because of the potential risk of causing psychological harm, especially when dealing with personal or sensitive topics.

Even if you do successfully conduct audience research, the results are not always that enlightening. The average film viewer cannot always put into words what a film means to them in quite the same way as a professional film critic.

Nevertheless, as I argue in a chapter for the recent publication The Routledge Companion to World Cinema (Routledge, 2017), film audience research can enhance our understanding of how films work and even challenge certain assumptions.

Mixing methods

My own research on the audiences for European films has combined three main methods and sources. Firstly, I use cinema admissions figures from sources like the European Audiovisual Observatory’s LUMIERE database to determine how many people watch particular films or types of films (e.g. comedies, dramas, horror films) in different European countries.

Secondly, I draw on large-scale audience surveys such as the European Commission’s (2014) Current and Future Audiovisual Audiences report or the British Film Institute’s (BFI) ‘Cinema Exit Polls’ to profile film audience in terms of age, gender, nationality, social grade or educational qualifications, as well as understand why people are drawn to particular titles.

Finally, when the help of colleagues from across Europe, I’ve conducted audience focus groups with over 140 participants in five European countries (i.e. Britain, Germany, Italy, Poland and Bulgaria), to get a deeper understanding of how audiences make sense of particular films.

Each of these methods has its own flaws – viewing figures for non-theatrical platforms are scarce; survey questions can be reductive and misunderstood; and focus groups are not always representative and the results are often quite difficult to interpret, particularly when discussions are translated from another language and the transcriptions only capture verbal forms of communication.

Nevertheless, combining these qualitative and quantitative sources allows one to build up a fairly robust picture of how audiences engage with European films and can even challenge our assumptions about how such films work.

Challenging assumption

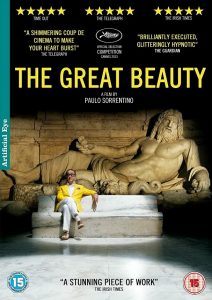

For example, given the emphasis which distributors often place on the director, reviews, festival recognition and awards when marketing European films, it is interesting to note that few survey respondents or focus group participants said they were drawn to these elements. Instead, they were much more likely to be attracted by the film’s story or genre.

Similarly, looking at the way certain European films are a box office success in some countries but a flop in others, one might assume that different countries have radically different tastes in films.

In fact, the focus groups I conducted across Europe showed remarkable similarities in terms of the films people liked and disliked, as well as their reasons why. There was much more difference in terms of age and gender than nationality.

None of this is to suggest film scholars should abandon their careful analysis of film texts in favour of only listening to what audiences say about films. But combining textual analysis with audience research certainly allows us to test some of our assumptions about how films really work.

Dr Huw Jones is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Southampton. His research on European film audiences formed part of the HERA-funded ‘Mediating Cultural Encounters through European Screens’ (MeCETES) project (www.mecetes.co.uk). An extended version of this blog is available in Rob Stone, Paul Cooke, Stephanie Dennison and Alex Marlow-Mann (eds.) Routledge Companion to World Cinema (Routledge, 2017).

Figure 1. Publicity material for European films often emphasis directors, awards, festival recognition and reviews. Yet audience research suggests viewers are more attracted by the film’s story and genre