By Joanna Redden, Associate Professor, Information and Media Studies, Western University, Canada

In 2019, former UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston said he was worried we were “stumbling zombie-like into a digital welfare dystopia.” He had been researching how government agencies around the world were turning to automated decision-making systems (ADS) to cut costs, increase efficiency and target resources. ADS are technical systems designed to help or replace human decision-making using algorithms.

Alston was worried for good reason. Research shows that ADS can be used in ways that discriminate, exacerbate inequality, infringe upon rights, sort people into different social groups, wrongly limit access to services and intensify surveillance.

For example, families have been bankrupted and forced into crises after being falsely accused of benefit fraud.

Researchers have identified how facial recognition systems and risk assessment tools are more likely to wrongly identify people with darker skin tones and women. These systems have already led to wrongful arrests and misinformed sentencing decisions.

Often, people only learn that they have been affected by an ADS application when one of two things happen: after things go wrong, as was the case with the A-levels scandal in the United Kingdom; or when controversies are made public, as was the case with uses of facial recognition technology in Canada and the United States.

Automated problems

Greater transparency, responsibility, accountability and public involvement in the design and use of ADS is important to protect people’s rights and privacy. There are three main reasons for this:

- these systems can cause a lot of harm;

- they are being introduced faster than necessary protections can be implemented, and;

- there is a lack of opportunity for those affected to make democratic decisions about if they should be used and if so, how they should be used.

Our latest research project, Automating Public Services: Learning from Cancelled Systems, provides findings aimed at helping prevent harm and contribute to meaningful debate and action. The report provides the first comprehensive overview of systems being cancelled across western democracies.

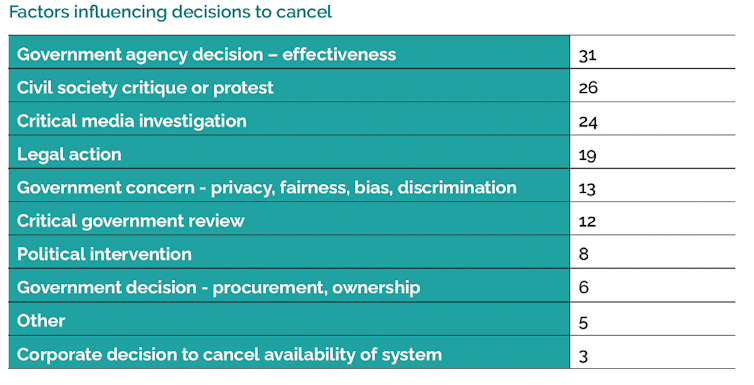

Researching the factors and rationales leading to cancellation of ADS systems helps us better understand their limits. In our report, we identified 61 ADS that were cancelled across Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand and the U.S. We present a detailed account of systems cancelled in the areas of fraud detection, child welfare and policing. Our findings demonstrate the importance of careful consideration and concern for equity.

Reasons for cancellation

There are a range of factors that influence decisions to cancel the uses of ADS. One of our most important findings is how often systems are cancelled because they are not as effective as expected. Another key finding is the significant role played by community mobilization and research, investigative reporting and legal action.

Our findings demonstrate there are competing understandings, visions and politics surrounding the use of ADS.

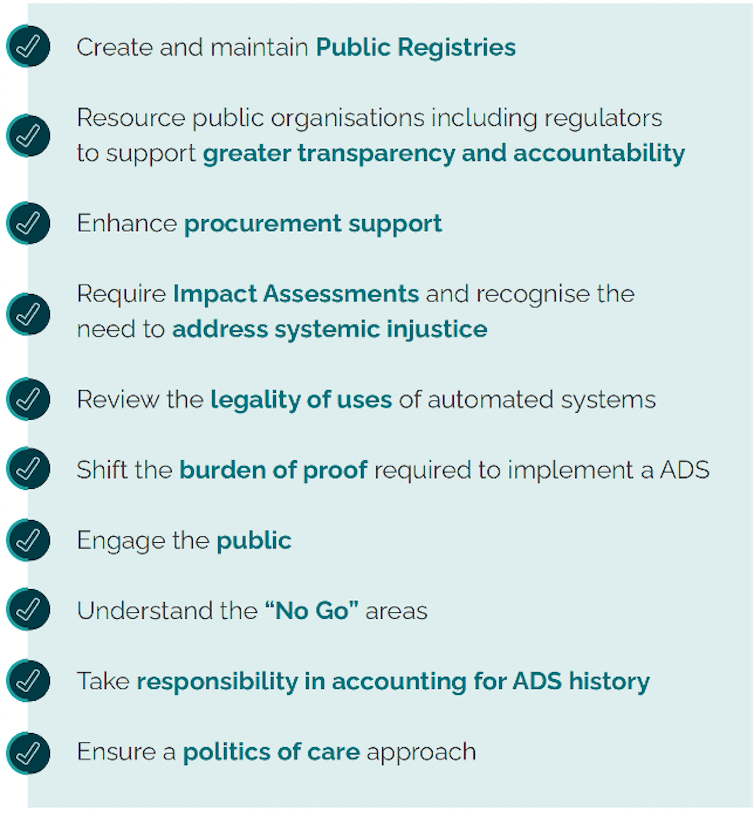

Hopefully, our recommendations will lead to increased civic participation and improved oversight, accountability and harm prevention.

In the report, we point to widespread calls for governments to establish resourced ADS registers as a basic first step to greater transparency. Some countries such as the U.K., have stated plans to do so, while other countries like Canada have yet to move in this direction.

Our findings demonstrate that the use of ADS can lead to greater inequality and systemic injustice. This reinforces the need to be alert to how the use of ADS can create differential systems of advantage and disadvantage.

Accountability and transparency

ADS need to be developed with care and responsibility by meaningfully engaging with affected communities. There can be harmful consequences when government agencies do not engage the public in discussions about the appropriate use of ADS before implementation.

This engagement should include the option for community members to decide areas where they do not want ADS to be used. Examples of good government practice can include taking the time to ensure independent expert reviews and impact assessments that focus on equality and human rights are carried out.

We recommend strengthening accountability for those wanting to implement ADS by requiring proof of accuracy, effectiveness and safety, as well as reviews of legality. At minimum, people should be able to find out if an ADS has used their data and, if necessary, have access to resources to challenge and redress wrong assessments.

There are a number of cases listed in our report where government agencies’ partnership with private companies to provide ADS services has presented problems. In one case, a government agency decided not to use a bail-setting system because the proprietary nature of the system meant that defendants and officials would not be able to understand why a decision was made, making an effective challenge impossible.

Government agencies need to have the resources and skills to thoroughly examine how they procure ADS systems.

A politics of care

All of these recommendations point to the importance of a politics of care. This requires those wanting to implement ADS to appreciate the complexities of people, communities and their rights.

Key questions need to be asked about how the uses of ADS lead to blind spots because of the way they increase the distancing between administrators and the people they are meant to serve through scoring and sorting systems that oversimplify, infer guilt, wrongly target and stereotype people through categorizations and quantifications.

Good practice, in terms of a politics of care, involves taking the time to carefully consider the potential impacts of ADS before implementation and being responsive to criticism, ensuring ongoing oversight and review, and seeking independent and community review.