In this second project blog, the research team reflect on how Covid-19 and the restrictions it has placed on all our lives, has led to methodological, ethical and practical challenges in working with focus groups on parental buy-in for linking and analysing data about families. They outline the challenges they face and how they’re adapting their approach.

For the next stage of our project, we’re conducting focus groups to explore how particular social groups of parents understand and talk about their perspectives on data linkage and predictive analytics. Back in early 2020, we were optimistic about the possibility of being able to conduct these groups face-to-face by the time we reached this stage of our research. Now though, it’s clear we’ll need to move online, and we’ve been thinking about the issues we’ll face and how to deal with them.

Questions we’re grappling with include:

- What might moving online mean for how we recruit participants?

- How can we best organise groups and engage parents with the project?

- How can we develop content for online groups that will firstly, encourage parents to contribute and enjoy the research process, and secondly, be relevant to our research endeavour?

What will moving online mean for recruiting participants?

Our intention was – and still is, to hold focus group discussions with homogenous groups of parents, to explore the consensus of views on what is and isn’t acceptable (social licence) in joining together and using parents’ administrative records.

We’re using the findings from our earlier probability-based survey of parents to identify social groups of parents whose views stand out. These include home-owning parents in professional and managerial occupations, who have stronger social licence, and mothers on low incomes, Black parents, and lone parents and parents in larger families living in rented accommodation, who tend to have weak or no social licence.

Our original plan was to recruit participants for our focus groups by contacting local community and interest groups, neighbourhood networks, services such as health centres and schools, workplaces and professional associations. We still plan to do this, but we’re concerned that the pandemic is placing huge pressures on community groups, services for families and businesses and we may need to be prepared that helping us to identify parents to participate in research may not be a priority or, as with schools, appropriate.

So we’ve also been considering recruitment through online routes, such as advertising on relevant Facebook groups; using Twitter and putting advertisements on websites likely to be accessed by parents. It’ll be interesting to see if these general reach-outs get us anywhere.

An important aspect of recruitment to our study is how to include marginalised parents. This can be a conundrum whether research is face-to-face or online. Face-to-face we would have spent quite a bit of time establishing trust in person, which is not feasible now. Finding ways to reach out and convince these parents to participate is going to be an additional challenge. Our ideas for trying to engage these parents include the use of advertising via foodbanks, neighbourhood support networks and housing organisations.

And there’s the additional problem for online methods, revealed in inequalities of online schooling, of parents who have limited or no online access. Further, Covid-19 is affecting parents living in poverty especially and we don’t want to add to any stress they’re likely to be under.

Enticing affluent parents working in professional and managerial occupations to participate may also be difficult under the current circumstances. They may be juggling full-time jobs and (currently) home schooling and feeling under pressure. Either way, marginalised or affluent, we think we’ll need to be flexible, offering group times in evenings and at weekends for example.

How should we change the way we organise groups and engage parents with the project?

We know from reading the literature that online groups can face higher drop-out rates than face-to-face. Will the pandemic and its potential effect on parent’s’ physical and mental health mean that we face even higher drop-out rates? One strategy we hope will help is establishing personal links, through contacting participants and chatting to them informally before the focus group takes place.

We’ve been mulling over using groups containing people who know each other, for example if they’re members of a community group or accessed through a workplace, and groups that bring together participants who are unknown to each other. Because we’re feeling a bit unsure about recruitment and organisation, we’ve decided to go down both routes as and when opportunities present themselves. We’ll need to be aware of this as an issue when we come to do the analysis though.

We’re also thinking to organise more groups

and have fewer participants in each group than we would have done face-to-face

(after all, we’re not going to be confined by our original travel and venue hire budget). Even in our online research team meetings we

can cut across and interrupt each other, and discussion doesn’t flow in quite the

same way. Reading participants’ body language and non-verbal cues in an online focus group is going to

be more difficult. Smaller numbers in

the group may help a bit, but it can still be difficult to see everyone if, for

example, someone is using a mobile phone.

We’ll just have to see how this goes and how best to handle it.

There’s also a dilemma about how many of the project team to involve in the focus groups. We’ll need to have a team member to facilitate the group, but previous research shows it might be useful to have at least one other to monitor the chat and sort out any technical issues. But with a group as small as 4-6 participants will that seem off putting for parents? It’s all hard to know so may be a case of trying it in order to find out!

What should we consider in developing content that’s engaging for parents and relevant to our research?

What we’ll miss by holding our group discussions online is the settling in and chatting and putting us and our participants at ease – how are you, would you like a drink, there’s some biscuits if you want, let me introduce you to … and so on. We don’t think that we can replicate this easily.

But we’ve been pondering our opening icebreaker – should we ask something like….

‘If you could be anywhere else in the world where would you be?’

or

‘What would be the one thing you’d pack in a lockdown survival kit?’

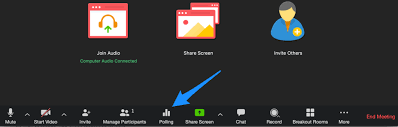

And we’re also planning to use a couple of initial questions that use the online poll function. Here’s an instance where we think there’s an advantage over in-person groups, because participants can vote in the poll anonymously.

After that, we’ll be attempting to open up the discussion to focus on the issues that are at the heart of our research – what our participants feel is acceptable and what’s not in various scenarios about the uses of data linkage and predictive analytics.

Ensuring the well-being of parents after focus groups is always important, but with online groups may be harder if the participants are not identified through community groups in which there’s already access to support. We plan to contact people after groups via email but it’s hard to know if parents would let us know even if groups presented issues for them. We have also given some thought to whether we could use online noticeboards for participants to post any further comments they may have about social licence after they’ve had time to reflect, but do not know realistically if they would be used.

It’ll be interesting to see if the concerns we’ve discussed here are borne out in practice, and our hopeful means of addressing them work. And also, what sort of challenges arise for our online focus group discussions that we haven’t thought of in advance!

If you have any ideas that might help us with our focus groups, please do get in touch with us via datalinkingproject@gmail.com