World War One, Student Protests in China and the Foundation of the Chinese Communist Party

Within the centenary commemorations of the First World War, one history-making aspect that is often overlooked is what the war had to do with the foundation by young Chinese intellectuals of the Chinese Communist Party, the party that continues to govern China today. In this Blog post, Elisabeth Forster discusses what was fought over in China’s war of ideas.

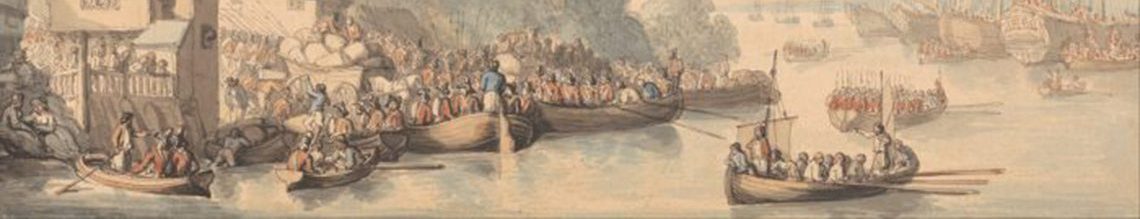

‘Chinese labourers at Boulogne August 1917’, Ernest Brooks [Public domain], via Wikimedia.

China entered the First World War in 1917, not by sending soldiers, but by dispatching labourers to help the British and French armies in France with their everyday toils; they carried their luggage, for example, and dug trenches.

The Chinese government’s goal was to reclaim German colonial concessions in one of its provinces, Shandong, a peninsula in the Northeast. Like so many other countries, Britain among them, Germany had obtained these concessions in the imperialist ‘scramble for China’ in the nineteenth century.

China’s strategy to regain these concessions had not factored in the rise of a new power in the region: Japan. Japan, too, was faced with the threat of being colonised by Western imperialism in the nineteenth century. But contrary to China, it had managed to Westernise and modernise its military very quickly. In the late-nineteenth century, Japan was starting its own imperialist venture in East Asia that would eventually result in its invasion of China in the 1930s and in its attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941 in the Pacific theatre of the Second World War.

During the First World War, Japan saw an opportunity to expand its territory and sphere of influence. Japan declared war on Germany and occupied the German concessions in China as early as 1914. Over the next few years, it concluded secret treaties with the Allied Powers and with the Chinese government, according to which these concessions should formally go to Japan after the end of the war. When the Paris Peace Conference convened in Versailles (January 1919-January 1920), it gave the formerly German concessions to Japan.

It was the reactions of the Chinese public — and especially its students and intellectuals — to this that contributed to the foundation of the Chinese Communist Party.

The Chinese public did not approve of the territorial deal at Versailles. On 4 May 1919, China’s students started to protest against Japan, against foreign imperialism and against its own government, which had agreed to the deal. The protests began in Beijing on the Square of Heavenly Peace (Tian’anmen Square) and soon spread to other cities. Before long, Chinese newspapers had invented the name ‘May Fourth Movement’ for the protests.

Where does the foundation of the Chinese Communist Party come in? Chinese intellectuals had long had an urgent interest in Western ideas — science and technology, philosophy, feminism, democracy and communism in all its forms. Communism was initially not very popular, even though it gained some traction after the Russian October Revolution of 1917. The interest in these Western ideas, like in so many other parts of the world at the time, was rooted in Western imperialism. Chinese intellectuals suspected that the roots of Western strength lay not only in its weapons, but also in its culture and they sought to tap into this strength by adopting Western ideas too.

The May Fourth protests of 1919 reinforced this. They boosted students’ anti-imperialist fervour; their feeling of empowerment; their enthusiasm for everything new, including new Western political ideas such as communism. Newspaper reports made it appear that the protests were not only about the formerly German concessions. They suggested that they were also about a struggle between those Chinese intellectuals who supported the new ideas (equated with the protesters) and those who were against them (equated with those who tried to suppress the protests). Equating the protests with the intellectual disagreements was not quite accurate, but a rather coincidental impression created by conspiracy theories and rumours the Chinese newspapers were spreading before and during the protests.

At the end of 1919, China had not only refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, it was also abuzz with new, Western ideas, among them communism. A number of communist associations were founded in its wake. One of them, located in Shanghai, was with help from Soviet Comintern agents and under participation of an as yet unknown Mao Zedong, restructured in 1921. This was the Chinese Communist Party, which is still in power today.

Elisabeth Forster

Elisabeth Forster is Lecturer in Modern Chinese History at the University of Southampton. Her book, 1919 – The Year That Changed China: A New History of the New Culture Movement (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018) explores why nobody in China anticipated at the beginning of 1919 that ideas like communism would become popular in the country, and why this was obvious to everybody by the end of the year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.