Author: Kenneth Norwood

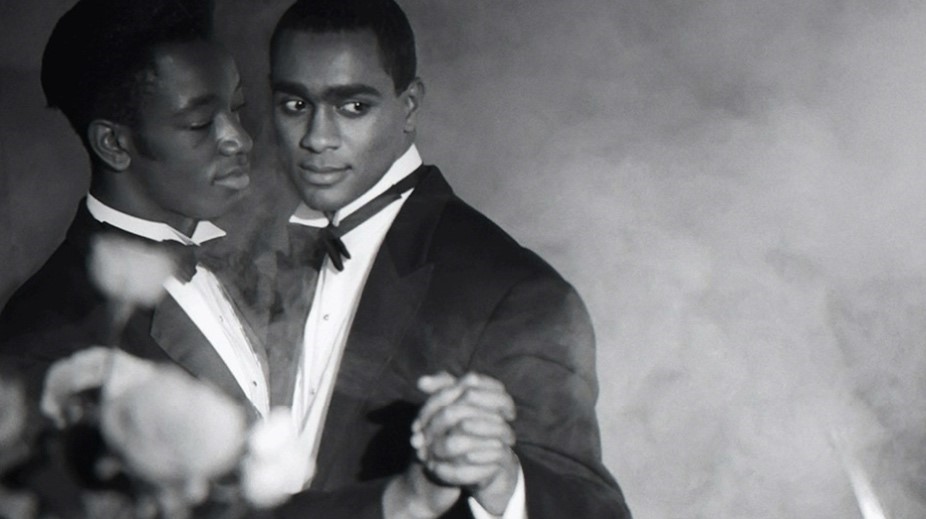

Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989) makes me cry every time I watch it. My first time seeing it was in the Lincoln Centre in New York City– privately–on a 35-mm reel via a projector. As it clicked and fluttered away in the darkness, spitting out visual poetry of black and white silhouettes of dark men in their most regal of forms on the wall; I saw them loving one another with no shame as if every breath and waltz was their last. I knew I had a place in time at that moment. Now that Langston is a permanent installation in the British Tate, I felt that the movie would finally reach those who never could grasp where modern queer cinema’s turning point actually took place. It was a new visual language crafted by Isaac Julien in order to express his retelling of a Queer Harlem Renaissance and the life of Langston Hughes in order to connect Blacks throughout the diaspora. It also was the fire that illuminated my reflection in my own Black American history and led me down the path to become the Black queer historian I am today. Everyone needs to have this moment! You need to find yourself in your nation’s past –you have to! I cannot stress how imperative this action is to build a sense of self and belonging in the present and future for the Black population. I, despite being queer and Black, benefit from American imperialism in ways that were not apparent to me until I left the states.

When I saw and heard that Black Britons were being taught only MLK and Malcom X quotes for Black History month, and the explosion that was the global acknowledgment of Juneteenth this year; I knew right then and there that my Black American culture was global and rode on the coattails of the empire to some extent–this scared me. It scared me a lot because I wanted to know more about the Black British timeline–with an emphasis on the queer leaders. I had to then remind myself of the past labor that was required of me to find Bayard Rustin, Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Essex Hemphill, Audre Lorde, and other Black Queer folks of the American past. But who were these Black queer British folks and where were they on screen? Julien, being Black Queer and British himself, was a start for me. Films like Young Soul Rebels (1991) took me to a place in Britain that most Black Americans don’t get to see. The pressure and tension of the times, and the class and racial alignment within the ongoing fight against fascisms, racism, and classism were so prominent in the film’s narrative. But there were other directors that I stumbled on during this search. Ajamu X’s Homecoming (1995) took me through South London and gave me a queer history lesson on the thriving and distinctive Black gay movement that took place there in the 1980s and 90s. While doing this, he also showcased his focal point as an artist; which shows his pioneering framing of Black masculinity through its subversion with fem-play and power.

Both Julien and Ajamu’s work scratch the surface for me when it comes to Black queer British filmmakers. While short films like BEYOND There’s always a Black issue Dear (2018) explores and celebrates Black LGBT identities in Britain, others like actor and director Rikki Beadle-Blair and his filmography of Black queer British cinema, the film Adaora Nwandu’s Rag Tag (2006), Forbidden Games: The Justin Fashanu Story (2017), and other titles in between both commercial and on the art circuit, continue to cave out stories for people like me in the UK.

Your history matters and seeing yourself on screen is a part of that journey. Sadly, in a state of being Black throughout the diaspora, in order to begin tracking one’s Black history, we must grapple with the devastating systems of racism through the lens of colonialism and white supremacy in order to even see ourselves in the past. But decolonization and dismantling white supremacy is a process, not a single act. And in order to find one’s own history, we must know that the story doesn’t stop and start at any particular point.