In the southwest of France, a queue starts to form. Progressing forward slowly over the next hour, countless men and women silently wait in eager anticipation: with the ticket they receive, they shall access an enclosed space, which, as many previous visitors have claimed, may radically enrich or challenge their understanding of what it means to be human. As they enter, a wondrous display of images come alive: before them, the wall becomes a canvas for series of simplistically profound gestures, each revealing some thought on identity, nature, faith, fear, life, and death. Lost in awe, the crowd are reduced to silence as the projections begin to dance.

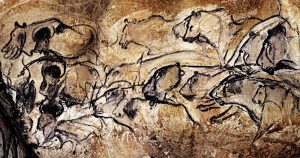

This is, of course, no ordinary cinema – I am in fact describing Lascaux II, a facsimile of the original Lascaux caves, where paintings dating to around 15,000 BCE were discovered and presented to the public through 1948 to 1963 – but I believe the prehistoric cave art represented there represents a form of cinema nonetheless.

Figure 1. A recreation of ancient cave paintings in Lascaux II (image from Semitour)

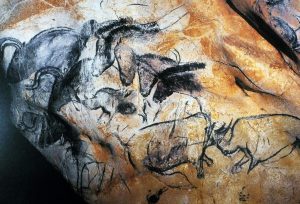

In his 2010 3D documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, recording one of the last expeditions into the Chauvet Caves (where paintings dating back to almost 30,000 BCE were discovered), Werner Herzog makes a fascinating observation: many cave paintings have a distinctly animated and cinematic quality. The overlapping of gestures (as seen in Figure 2) shows the ‘primitive’ man’s attempt to express movement within a single image. Of course, film is fundamentally reliant on the illusion of movement created by a rapid succession of distinct frames, but this can still be distinguished from sequential art in that distinct frames of the same motion are not typically shown in a composite image (as, for example, with the panels of comic books and film storyboards).

Archaeologist and filmmaker Marc Azéma, from two decades of studying movement in animal cave paintings, concluded likewise that cave art held the same essential appeal as that of cinema – that is, in its attempt to replicate and convey natural movement – and recreated animated loops from traces of paintings to demonstrate.[1]

Figure 2. Some of the earliest-known examples of figurative drawings, found in the Chauvet Caves (image from Bradshaw Foundation)

The first audiences of the earliest cinematic experiments were often fascinated with the representation of movement in what may now be considered mundane or incidental details. With Le Repas de Bébé, for example, a 1895 documentary short film directed by cinematic pioneer Louis Lumière, it is recorded that the audiences were particularly fascinated with rustling leaves in the background. A common myth of early cinema holds that contemporary audiences were allegedly terrified of a considerably simple projection of an approaching train in L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, another short released in 1896 (seen in Figure 3). As Dai Vaughn considers, what this reveals is that people were most significantly impressed by the ability of a camera to both carry the ferocity of large moving bodies and capture spontaneities and gestures unable to be shown in photography and the painted backdrops of theatrical productions.[2]

French inventor Léon Bouly patented a device capable of both projection and photography, which was later sold to the Lumière brothers (with which they filmed Le Repas and L’Arrivée), naming it a ‘cinématographe’ from the Latinised form of the Greek ‘kinema’, meaning ‘movement’, and ‘graphein’, meaning ‘to write’. The concept and name of cinema evolved from – and its development and popularity build on – its ability to capture movement.

The idea here that movement contributes a unique quality to an artwork can be seen to foreshadow, though in perhaps a very limited form, the foundational formal appeal of cinema as a celebration of movement. It is, ultimately, this potential which gave rise to the growth, popularity and preservation of both film and cave art: no other contemporary medium than cave art for Palaeolithic society and cinema for the late 19th century Western society could so impressively capture both subtlety and strength represented in movement.

Figure 3. Frame from L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1896) (image from la Lucnarne)

Dominique Baffier, an archaeologist and cave art curator featured in Herzog’s documentary, considers that the inclusion of a horse with an open mouth makes the image ‘become audible to us’, suggesting also that the aggression of fighting rhinos can almost be heard (see Figure 4). This implies that, although evidently limited by resources, the paintings were intended to contain and induce a broader sensory experience in its audience.

The ‘primitive’ artist, as with the artist of any era, was no doubt distinguished by their relation to or experience with the natural world. Arnold Hauser argues that, if the representation of animals served a magical or spiritual function, then we can infer that the artists were seen as gifted with some magical sensitivity and hence venerated as such.[3] This new status, he writes, would have brought certain privileges, including the emancipation of food-seeking duties: a primitive form of Hollywood stardom or auteurship, perhaps.

Figure 4. Horses whinny and rhinos clash in Chauvert Caves (image from Amusing Planet)

Although cinema is not essentially defined by the inclusion of recorded sound, since ‘silent’ films were prominent for the first few decades of cinema (though music has always played an invaluable role), the value of its potential – and certainly its progression – is broadly defined by the reality and believability of sensorial impact. The latest IMAX cameras, with extended resolutions and greater quality, are now often praised as the pinnacle of contemporary cinematic achievement, with specific theatres integrated with 3D technology reserved primarily for showing the most expensively produced blockbusters.

The as-yet uncontested success of 2009’s Avatar can be in no small part attributed to its innovative usage of 3D technology, motion capture and CGI effects: positive criticism almost universally lists these features, and negative criticism often isolates the predictability of its narrative. The ability of cinema to produce an otherwise unique sensorial experience – defined by its ‘realism’ – appears essential to the main thrust of its public appeal: the camera, like the ‘primitive’ artist, is valued by the intimacy of its relation to the world it records, though the value and nature of intimacy has developed and changed.

Figure 5. An IMAX screen (image from BFI)

Why cave art was featured in locations that would have been, as Ira Konigsberg considers, incredibly difficult to reach,[4] remains something of a mystery, but perhaps, like contemporary cinema, ‘primitive’ humans found value in an environment which is both communal and private. Large areas in caves indicate that multiple people (though likely only a few) could visit the sites of artworks at the same time,[5] indicating that the artists likely intended the viewing of their work to be a public experience. Although cinema is valued by personal and private faculties (namely, a unique reception of light and sound, and a subjective inference of meaning), the experience of cinema going is undoubtedly shaped by the crowd surrounding the individual: it is why we go to the cinema with our friends and family, etc.

The difficulty of access to caves may be somewhat comparable to the decision of modern audiences to continue paying for cinema tickets despite their increasing price and the apparent ease of illegal piracy: the intimacy of the relationship with the image is often thought to be intensified by the difficulty of our work in affording entry, just as ‘primitive’ humans evidently persisted, despite the apparent physical difficulty, in creating and viewing their artwork. We treat going to the cinema, no doubt influenced by the marketing of production companies, as an enjoyable social, celebratory and romantic experience – but almost always as a treat or novelty.

Furthermore, in the same way that caves provide security from the threats of aggressive predators and weather, cinema has developed itself an economic dependency on the viewer’s desire for popcorn, snacks and comfortable seating. The cinema and the cave have always been both a sanctuary and emotional captivation, despite – or maybe in face of – the darkness within.

Since, therefore, most known cave art reveals a desire to represent life, often expresses some degree of movement, volume and sound, and is featured in an enclosed public space with limited lighting, I believe drawing connections to the structure of cinema is appropriate and substantial. What this shows, if it is true that the aesthetic, spiritual and ideological sensitivities which gave rise to cinema laid dormant in our very human nature, waiting to be unearthed, is that the study of cinema should is not merely incidental or peripheral as an academic field: it is a study of how humans have always wanted to view the world.

Jonny Rogers, Film and Philosophy

FILMOGRAPHY:

L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat / The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station. Auguste Lumière, Louis Lumière. Société Lumière. 1896

Avatar. James Cameron. Lightstorm Entertainment, Dune Entertainment, Ingenious Media, 20th Century Fox. United States, United Kingdom. 2009.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Creative Differences, History Films, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Arte France, Werner Herzog Filmproduktion, More4, IFC Films, Sundance Selects. 2010.

Le Repas de Bébé / Baby’s Dinner. Louis Lumiére. France. 1895.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Gibbs, Patrick, Marc Azema animation (YouTube, 2012), Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8exsw6yKXw [Accessed 2 July 2017]

Hauser, Arnold, The Social History of Art: From prehistoric times to the Middle Ages (Volume One) (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1962), p. 17

Konigsberg, Ira ‘Cave Paintings and the Cinema’, Wide Angle, 18 (2), 1996, pp. 7-33

Vaughn, Dai, ‘Let there be Lumiere’, in Thomas Elsaesser, eds, Early cinema: space, frame, narrative (London: BFI publishing, 1990), pp. 63-67

[1] Patrick Gibbs, Marc Azema animation (YouTube, 2012), Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8exsw6yKXw [Accessed 2 July 2017]

[2] Dai Vaughn, ‘Let there be Lumiere’, in Thomas Elsaesser, eds, Early cinema: space, frame, narrative (London: BFI publishing, 1990), pp. 63-67 (64-65)

[3] Arnold Hauser, The Social History of Art: From prehistoric times to the Middle Ages (Volume One) (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1962), p. 17

[4] Ira Konigsberg, ‘Cave Paintings and the Cinema’, Wide Angle, 18 (2), 1996, pp. 7-33 (8)

[5] Ira Konigsberg, ‘Cave Paintings and the Cinema’, Wide Angle, 18 (2), 1996, pp. 7-33 (11)