Interview with recent PhD graduate, Dr Louise Fairbrother

What was the subject of your research?

My research looked in detail at how the town governments of Southampton and various other English towns organised their industry and trade in the sixteenth century. It focussed specifically on the way in which they controlled the groups involved. In Southampton’s case, this was by the use of devices such as licences, oaths and ordinances on the three groups of the burgesses, the freemen and the strangers.

What attracted you to this subject?

I realised at an early stage that although there was considerable diversity in the nature and structure of town administrations across England, the majority of towns were nevertheless governed by an assembly of men within which was a smaller, senior group who wielded the most power. In Southampton this group was formed of burgesses. Although in some towns the terms ‘burgess’ and ‘freeman’ were interchangeable, this was not the case in Southampton. The town government ensured the continued separation of the two groups even though both held the franchise, that is, the right to carry on a craft or trade. The terms ‘burgess’ and ‘freeman’ often meant different things in different towns which made direct comparisons difficult.

What new insights did you have about social distinctions in Southampton in this era?

The status of an individual was often determined by membership of a particular group. Burgesses were undeniably the group with the most power and highest social standing. Its members were often of the mercantile crafts, and although only burgesses had access to the higher levels of political power, non-burgesses were permitted to hold some lower offices. Freemen, on the other hand, were those persons who paid a fine to be allowed the freedom to set up in a craft or trade in the town and to be admitted to a guild or corporation if one existed for their occupation.

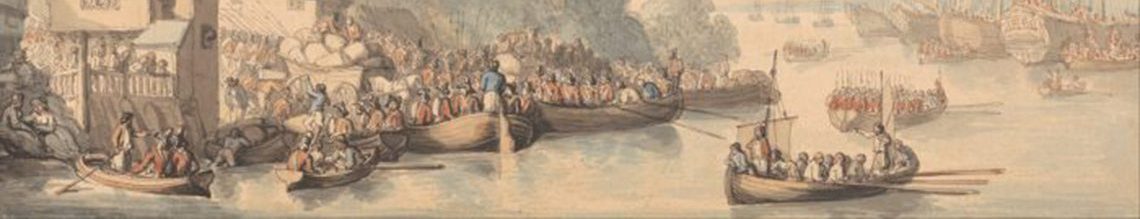

document of 1543 (SCA, SC 2/7/4)

Copyright: Southampton City Archives

In Southampton, they were also known as ‘commoners’ and later as ‘free commoners’. This term ‘commoners’ is extremely problematic as it appears to have had several meanings during the period. Freemen, at least in the sixteenth century, were inconspicuous as a unified group in the town, unlike freemen in many other English towns. The establishment of the Register of Free Commoners in 1613/4 is perhaps an indication they were becoming more of a discrete and visible group—that they had at last found their collective voice.

Strangers, resident and non-resident, were the third group who were manufacturing or trading in the town. Those strangers residing in the town were assessed for ‘stall and art’ payments in order to trade or carry on a craft. This term appears to have been unique to Southampton. Although the strangers were without question the largest group of the three, they were also generally the least wealthy and held the least power. Having said that, several of those who arrived as strangers in the town subsequently entered the burgesship and rose to the position of mayor.

What new insights did these fine-grained distinctions reveal about Southampton’s social history?

Although it is clear that the three groups were distinct from one another, close collaborations could exist between them. Within many occupations a combination of burgesses, freemen and strangers worked alongside one another. Town ordinances, which regulated the clear demarcations between the groups, may have been more flexible in practice than they were in principle. In 1544, a time of national emergency, the members of twenty-five of the town’s occupations were called upon to help maintain thirteen towers as part of the town’s defences. This shows the interrelationship that existed between the burgesses of the town council on the one side and the members of the craft and trade groups on the other.

What was the most important lesson you took from your PhD?

Southampton’s social history was unique in the context of other late medieval and early modern towns. In-depth studies of local communities still have new stories to tell about English urban environments of the past. On a personal level, the doctoral experience has shown me that however daunting a project may seem at the outset, by remaining focussed on research aims, it is possible to find answers to many of those questions which at one time seemed out of reach.

Louise Fairbrother was awarded a PhD from the University of Southampton in November 2018 with the thesis title of ‘Burgesses, Freemen and Strangers: The Organisation of Industry and Trade in Southampton, 1547 to 1603′. Her research utilised unique sources to reveal not only a part of Southampton’s history but also its place within the wider field of urban history.

She can be contacted at louisefairbrother@hotmail.co.uk

Leave a Reply