45 years ago, Louise Brown shocked the world as the first ‘test-tube baby’. Whilst in vitro fertilisation (IVF) was initially met with a knee-jerk revulsion, Louise’s birth has since been a turning point in the treatment of infertility. Could a child developed from artificial gametes undergo this same path?

As an aspiring clinical embryologist, I champion assisted reproductive technologies (ART) such as IVF. However, when I came across the idea of assisted reproduction using artificial gametes, termed ‘in vitro gametogenesis (IVG)’, my reaction was immediately apprehensive.

In the same manner as how IVF practice was initially received as scientists ‘playing god’, my thoughts concerned whether IVG fits into the natural order. Although artificial gametes produce artificial embryos, would full prenatal development of these cells lead to artificial life? This question brought my mind to Kazuo Ishiguro’s science fiction novel ‘Never Let Me Go’ which delves into the meaning of humanity through the lens of human cloning as a means of organ donation. Despite their unconventional origins of conception and development, I was moved to read the injustices imposed on the clones who processed our same fully human thoughts and feelings. Whilst I don’t find the novel’s cloning institutions morally or ethically appropriate, this warmed me to IVG technology and the belief that children potentially born from artificial gametes would still hold valuable and meaningful lives.

What IVG could have to offer

The more I researched the applications of IVG within the broader context of society, the more my support for this putative technology grew.

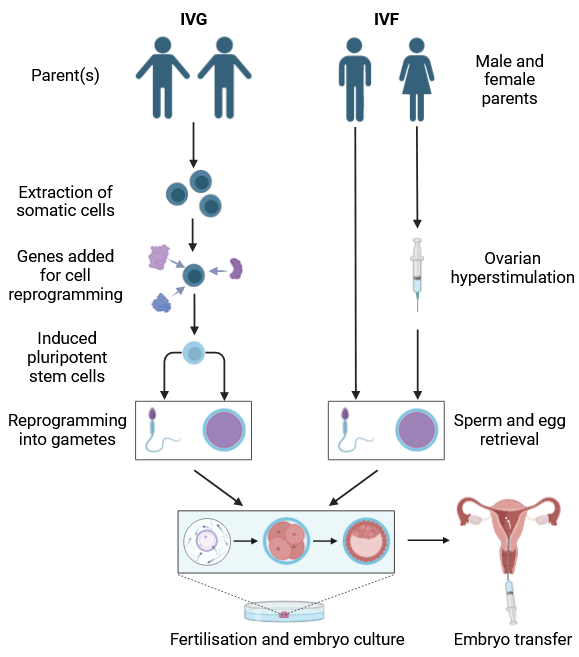

IVG obtains gametes via reprogramming somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells. Therefore, it offers infertile couples, and even same-sex couples, the ability to generate viable gametes and have genetically related offspring.

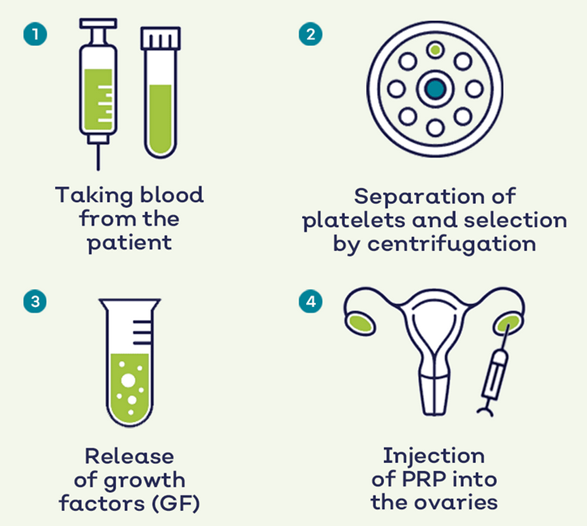

If made readily accessible, IVG may offer an alternative to the standard hormonal stimulation for egg retrieval, alleviating women from the physical and emotional demands of the procedure.

Due to DNA-damaging chemotherapy and radiation treatment, IVG would be especially useful amongst cancer patients who may not have the time to conduct cryopreservation at the risk of delaying urgent anti-cancer treatment.

IVG would also provide an unlimited production of embryos, opening more avenues for developmental research.

Ethical considerations

While IVG has demonstrated success in mice, significant research and resolution of ethical and legislative challenges are required before its applications become a clinical reality for humans.

The prospect of generating embryos from any somatic cell raises concerns regarding unauthorised gamete creation. For instance, it may enable celebrity DNA theft. Although legislation could mandate cell samples to only be obtained in clinical settings with formal consent, the system could be easily exploited.

Theoretically, ‘uni-babies’ may be possible, where a set of gametes are reprogrammed from a single individual.

It brings to question the impacts on adoption.

Combined with gene-editing tools like CRISPR, the unlimited supply of IVG embryos could potentiate embryo farming and accelerate the concept of ‘designer babies’.

With UK legislation ruling a 14-day cut-off for human embryonic research, it may be questioned whether this period should be extended for artificial embryos. However, particularly if IVG is used as ART, artificial embryos should be applied under the same legislation as natural ones.

A biotech startup, Conception, claims they are ‘quite close to being able to have proof-of-concept human eggs’ derived from blood cells. Although the successful application of IVG in humans is years away, I think it would be a revolutionary technology that positively eliminates reproductive barriers for future generations.

Very well written, with an excellent format and images. You’ve included interesting statistics and related it to personal ideas which…

This is a very well written blog, the format is as if you are talking directly to me. The ideas…

Love the Batman GIF :)

This is an excellent, well written blog. The narrative is engaging and easy to follow. It could be improved by…

This is a well-communicated blog. The it is written well with good use of multimedia. It could be improved with…