Heart failure is a condition that affects over 1 million people in the UK. According to the British Heart Foundation, around 200,000 people are diagnosed with the condition every year. The condition tends to be managed through medications or through various surgical interventions, depending on the cause of the heart failure. However, in severe cases, these interventions may not be effective and a heart transplant may be the only option. As the waiting list for donor organs continues to grow, the medical world has been desperate to find another option.

Artificial hearts, once nothing more than an idea in the realm of science fiction, are now an exciting reality. Ventricular assist devices supplement the function of failing hearts by replacing one aspect of the heart, whereas total artificial hearts are created to replace the heart entirely.

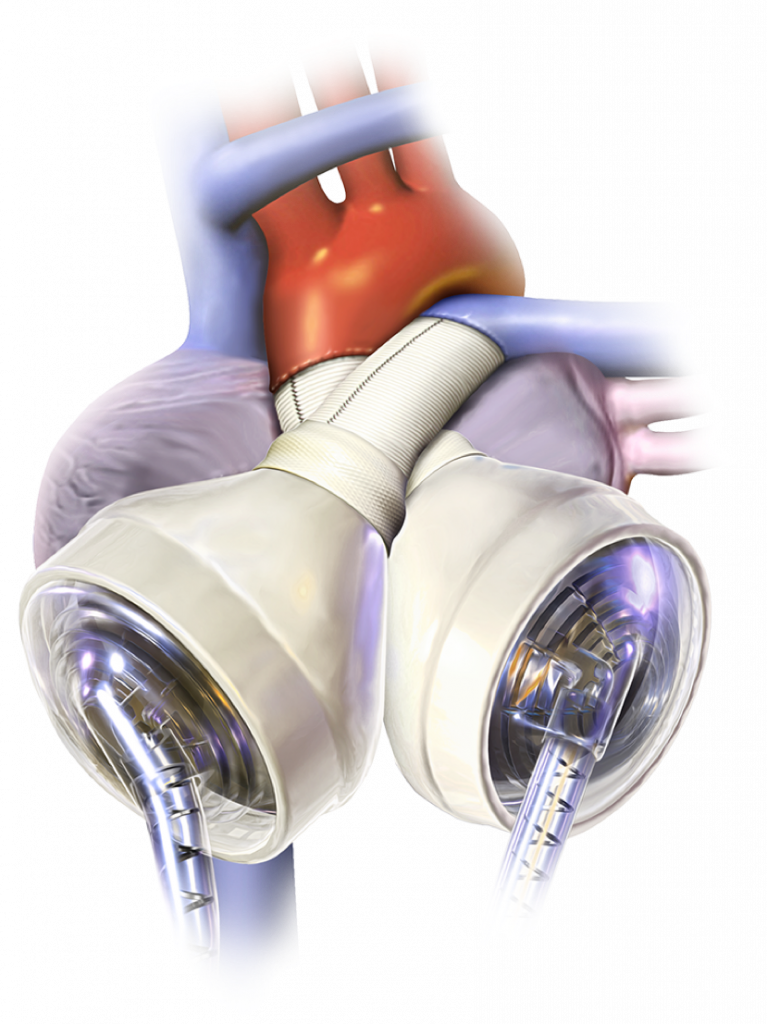

The company SynCardia has created the first commercially approved total artificial heart. This innovative device replaces the ventricles and 4 valves of the heart. It offers hope and an extended life expectancy to patients with end-stage heart failure. The longest a patient has lived with a SynCardia total artificial heart is 6 years and 9 months.

An intriguing current prototype for a soft artificial heart is being researched by ETH Zurich. It is formed from silicone and was created using 3D bioprinting, in an attempt to mimic the human heart as closely as possible in its form and functionality. However, this heart has a lifetime of only 3,000 pumps – the equivalent of 30-45 minutes.

Despite these incredibly impressive innovations, there is a clear problem; artificial hearts have been created as a bridge to a donor heart transplant, and the code has not yet been cracked on how to create a permanent artificial heart.

One of the greatest difficulties is creating a device that can meet the demands of the heart. Total artificial hearts must pump 8 litres per minute of blood with a blood pressure of 110mmHg, which requires an enormous amount of power. (More statistics on requirements in this article) Additionally, the procedure may lead to infection and there are other devastating side effects. A functioning heart is an essential part of life; the creation of a permanent artificial heart replacement would undoubtably change the lives of millions worldwide.

One of those lives could potentially be mine. Heart failure is a condition that has impacted my family and is something that I am at higher risk of. It is comforting to know that there are many interventions in place for the condition, should I be in the position of needing them. The fear of needing a heart transplant is one that I think about at times. I hope to make an impact in the research of artificial hearts in future. When taking the issues with durability, infection risk and economic barriers into consideration, it seems as though the creation of a permanent, accessible artificial heart replacement is an idea of the distant future. But I like to view things optimistically; technology is advancing extremely quickly – perhaps there will be a breakthrough sooner than it is believed.

Very well written, with an excellent format and images. You’ve included interesting statistics and related it to personal ideas which…

This is a very well written blog, the format is as if you are talking directly to me. The ideas…

Love the Batman GIF :)

This is an excellent, well written blog. The narrative is engaging and easy to follow. It could be improved by…

This is a well-communicated blog. The it is written well with good use of multimedia. It could be improved with…