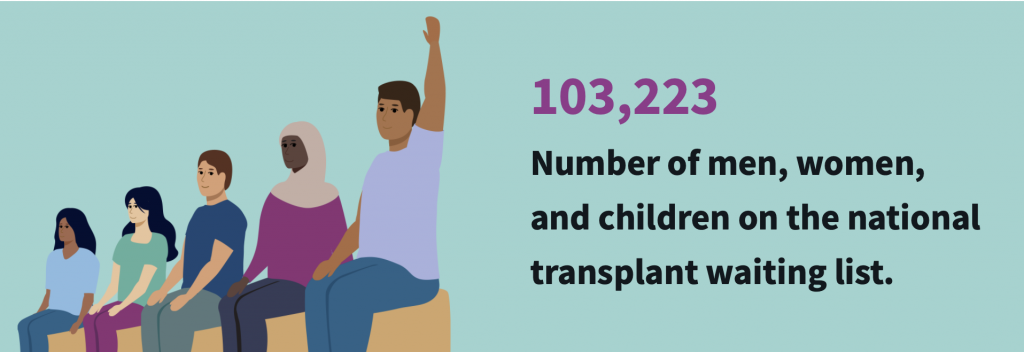

Over 100,000 people in the UK are waiting for an organ transplant and every 8 minutes another person is added to the list. However, there is a huge shortage of suitable donors meaning 17 people die each day waiting for a transplant.

With so many patients waiting and so few donors, when an organ becomes available for transplant, the decision of the correct recipient can be a difficult one. To aid this decision, healthcare providers use algorithms to decide who is next on the list to receive a transplant. Should a computer be trusted with such a life-or-death decision?

31-year-old Sarah Meredith fell victim to this algorithm whilst waiting for her liver transplant. Sarah was not made aware of the National Liver Offering Scheme (NLOS) algorithm that would be used to influence her wait time. When a liver becomes available for transplant, the algorithm calculates a transplant benefit score (TBS) for each patient based on 28 variables, mostly from the recipient – whoever has the highest TBS is offered the liver. Whilst the overall number of deaths whilst waiting for transplant has dropped since the introduction of this algorithm, younger patients are being made to wait far longer than before – Sarah waited over 2 years after being informed her wait time would be 68 days. 26 to 29 year olds are now waiting an extra 116 days due to the algorithm, suggesting it might disadvantage certain individuals.

My thoughts

The complexity of prioritising patients on waiting lists puts a heavy moral responsibility on medical professionals. Therefore, the use of an algorithm seems like a practical solution to take pressure off medical professionals and aid this difficult decision. However, in practice, a computer lacks the empathy and judgement of the human brain, so I don’t think they can be trusted to make decisions in life-or-death situations. Additionally, this algorithm overlooks reduction in life expectancy with increased transplant wait time – should we prioritise older, more vulnerable patients when doing so takes years off the lives of younger patients?

The solution?

Whilst current algorithms in use may not be 100% fair, I don’t think they should be scrapped. A new technology developed by the University of Bradford, OrQA (organ quality assessment), has been nominated for the Medipex NHS Innovation Award. OrQA uses technology similar to facial recognition to assess donor organs and match them to a recipient. AI like this, based on information from the donor rather than the recipient, provides an unbiased solution which will help healthcare providers reduce transplant waiting times. It is estimated to allow 100 more liver transplants a year; but, is this enough with over 10,000 people waiting for a liver transplant?

Are pigs the future?

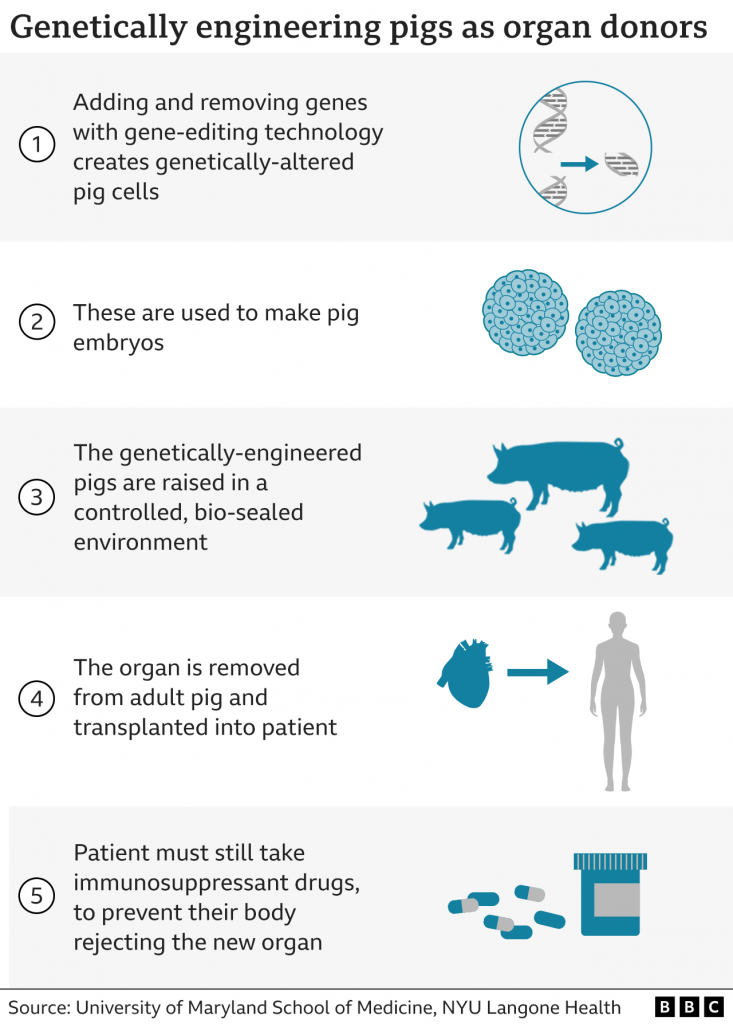

Growing new organs for transplant would quickly reduce waiting times. Scientists have explored the possibility of using pigs and xenotransplantation to do this. In 2022, David Bennet received the first ever pig heart transplant. The pig heart was genetically modified before being transplanted, and Bennet was given drugs to prevent immune rejection of the pig heart. Bennet lived for 2 months with his pig heart before it failed. In the current situation, I’m sure many would agree with me when I say I would be skeptical receiving a pig organ transplant. However, with more research, breeding genetically modified pigs and harvesting their organs for xenotransplantation could revolutionise the organ transplant process and remove the need for patients to put their lives in the hands of a computer.