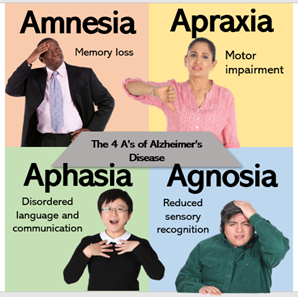

What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Having close personal experience with dementia, I often think about the subtle changes in behaviour and function that I noticed, but initially overlooked, in family members who were (much) later diagnosed. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases(1). It is a degenerative brain disease, where cell damage leads to complex brain changes that gradually worsen over time. Crucially, the slow progression of AD means that behavioural and physiological signs, or ‘biomarkers’ may present long before a diagnosis is even considered. I imagine many people who care for or love someone with dementia feel similarly, particularly as AD currently has no effective treatment and the current method of clinical diagnosis is criticised for cultural bias and inaccuracy. Early diagnosis is essential as the chance of reversing anatomic and physiologic changes decreases dramatically as the disease advances(2). Personally, I believe one of the most important benefits of early diagnosis is allowing people with dementia to open a dialogue about their ideal care plan, and express autonomy over their future.

I highly recommend reading “What I wish People knew about dementia” by Wendy Mitchell, which provides a great insight into how early diagnosis and acceptance of dementia can help individuals maintain independence and autonomy.

Towards Digital Detection

The race to improve diagnosis and treatment for AD is on. In 2023 there was even a $200,000 reward advertised for anyone who can prove that dogs can sniff out Alzheimer’s disease. Whilst MRI and PET molecular imaging of beta-amyloid and tau proteins are perhaps more promising, the cost and invasive nature of such methods precludes practical clinical applications(3).

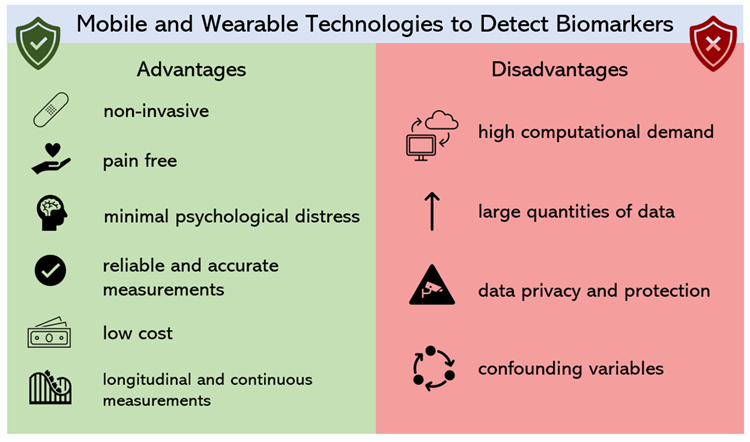

Interestingly, digital consumer technology can overcome these limitations with the added benefit of pre-symptomatic detection. What’s amazing is that cognitive, behavioural, sensory, and motor biomarkers can aid detection of AD 10 to 15 years prior to effective diagnosis(4). This allows leverage of existing technologies and sensors such as smartphone microphones and GPS systems.

Watch this quick video I put together to find out more…

Innovation or Invasion?

Whilst I do own both a smartphone and an (albeit old) smartwatch, the concept of these devices continuously monitoring everything from my speech to my walk and even the way I view an Instagram post, makes me slightly uneasy. However, I can’t deny the advantages of personal continuous monitoring for public health. The question is where do we draw the line? Could we be heading down a path where continuous passive monitoring involves cameras wired up in our home, even in our toilets?! (apparently yes! Find out more here).

I think the answer is purely personal – for some people continuous passive monitoring may be the difference between life and death, for others it might feel a little too 1984. For people experiencing cognitive decline, informed consent may complicate matters further. According to the Mental Capacity Act (2005), many people with dementia may be considered ‘Incompetent adults’ (I’m not a fan of that term) if they fail to understand the device, and cannot remember or communicate the reasoning for use. This means they would be legally unable to consent. Thankfully, the increasing nature of wearable technologies may mean that, in the future, many people will own devices decades before they are at high risk of AD, and thus can choose (at legal capacity) whether or not to install bio-monitoring software. Of course, if these devices continue to be solely commercial, then the financial accessibility of these devices may be limited – which is a whole other debate in itself.

Summary

Given the increasingly technological cultural landscape – our access to devices capable of passive monitoring is increasing. Considering the UK Alzheimer’s epidemic and our ageing population, it seems a waste to not make use of the endless potential health benefits of these devices (especially as many already monitor us for consumer metrics anyway)! Although the degree of monitoring may seem invasive, I think Alzheimer’s is a far bigger threat to our personal privacy and autonomy. Such developments could help people communicate with their families and manage symptoms before its too late.

References

- Dementia vs. Alzheimer’s Disease: What Is the Difference? | alz.org

- Kourtis, L.C. et al. 2019. Nature. 2, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0084-2

- Bao, W. et al. 2021. Front. Aging Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.624330

- Vrahatis, A. G. 2023. Sensors. 23, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23094184

- Stringer, G. et al. 2018. Int J Geratr Psychiatry. 33,7. https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fgps.4863

- Sun, J. et al. 2022. Sec. Brain Imaging and Stimulation. 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.972773