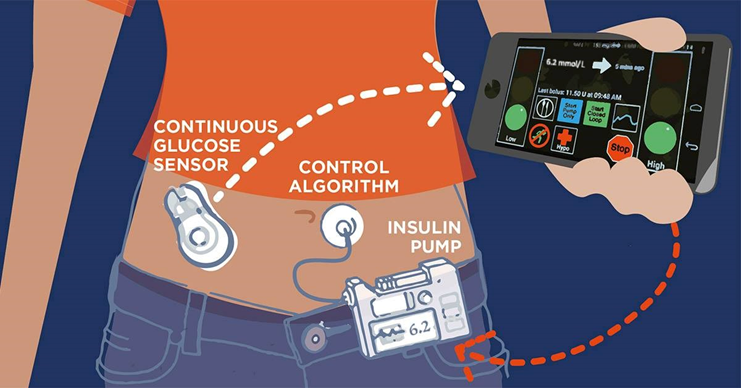

I was contemplating David Simpson’s lectures on sensors within prosthetics and was drawn to an article he attached outlining the artificial pancreas device for type 1 diabetics. The device, also called the closed loop system (CLS), wirelessly connects a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to an insulin pump to stabilise blood sugar levels automatically. This is revolutionary for diabetics who struggle to manage their blood sugars manually, and reduces the likelihood of long-term complications such as diabetic neuropathy (nerve damage). My mother is a type 1 diabetic, so I decided to look further into this.

A brief history of diabetes testing

Back in 600BC, scientists noticed that ants were attracted to the urine of those with diabetes and one brave (or questionable) lad personally confirmed its distinctive sweet taste. Fast forward to 1841 and we have the first clinical test for diabetes, before the 1940s produced urine test strips to quantify these results.

Today the glucometer, first developed in 1970, is still widely used. It relies on a fingertip pin prick to draw blood for the test strip, which is then inserted into the meter. The physics behind this is actually very interesting – the glucose in the blood sample reacts with glucose oxidase on the strip, generating an electrical signal. This translates into a digital readout of the glucose concentration.

CGM – tech for the internet age

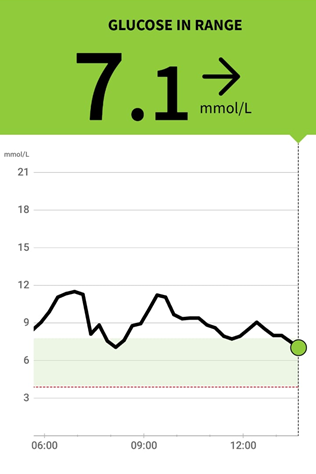

The truly ground-breaking CGM attaches on the arm and records glucose levels every 15 minutes, creating a graph that shows the fluctuations throughout the day, transmitted to a mobile app. Extra functionality shows rising or falling sugar levels, adding an important new level of precision to injection decisions. There’s still a fair bit of maths to go wrong here though, as I saw following one horrifying mistake that left my mother guzzling 375g of dissolved sugar to counter an overdose on her fast-acting insulin.

The CLS – a lottery win?

Significantly more automated, the CLS aims to stabilise sugars with minimal input by combining the CGM with an insulin pump. Whilst users still need to compute carbohydrate intake, the main job of the CLS is to prevent hypos overnight by delivering tiny doses of insulin to keep blood sugars level. Hypos occur when sugars drop below normal range and can be extremely dangerous if not resolved quickly.

A game-changer for lots of diabetics, one user claims it has “cut out about 90% of [their] low level dips into hypoglycaemia”. The principal drawback appears to be in roll-out due to relative cost. One CLS user told me it’s also a bit cumbersome as they have to move their injection sites around to avoid build-up of scar tissue which could stop the insulin from being administered properly.

Diabetes – no longer a chronic disease?

The prospect of a cure has been touted for years with no solutions yet. However, scientists have recently created tiny implants containing stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitor cells that can emulate a healthy pancreas and produce insulin. The hope is that the encapsulated cells are protected from the diabetic’s immune system which is intent on destroying them.

Researchers are highly optimistic, with some even claiming this may “turn into a cure a soon as 2024”. However, I noticed a potential ethical issue, as implementation of the implant is reportedly limited by shortage of donor stem cells. If this leads to a shortage of potentially curative therapy, how do they decide who gets it and who doesn’t?