Since the development of the Egyptian ‘Cairo toe’, prosthetic limbs have developed greatly. The Cairo toe was made from pieces of wood sculpted into the appearance of a toe and held together by leather thread. This simple model contrasts drastically to the modern-day prosthetics often constructed using metals and synthetic materials such as plastic and silicone which can provide individuals with high levels of functionality and are available with a range of different aesthetics.

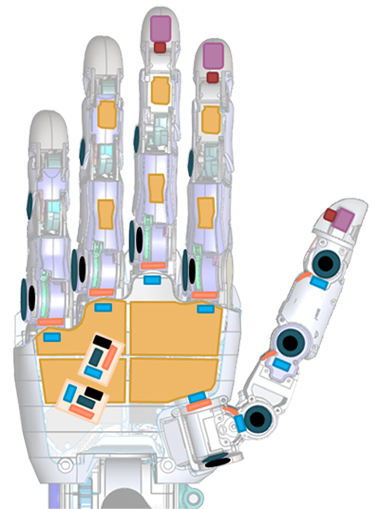

Scientists are constantly trying to improve prosthetics for their recipients. Recent developments have focused on the ability to control prosthetics in the same way we would control the natural limb – with our minds. Johns Hopkins University have developed the APL bionic arm which can be controlled by the human brain. In 2016, Melissa Loomis, who lost her arm after being bitten by a wild racoon, became the first recipient of this prosthetic and one of the only amputees at the time to be able to control her prosthetic with her mind. The arm receives inputs from her nerves in her nervous system which are interpreted by the arm and result in the desired output of movement. The prosthetic also has a range of sensors across it which send signals back to her nervous system allowing her to be able to detect temperature and provide some of the senses, such as touch, to the limb. This could be life changing to amputees like Melissa who said touch was ‘the thing she missed the most’ in an interview with Motherboard.

Whilst this was a huge leap forward in prosthetic science it is not without its disadvantages. The APL bionic arm is extremely expensive, and patients need to undergo a long invasive surgery known as targeted sensory innervation to allow the prosthetic to be connected to the patients nervous system. Whilst currently these factors make the prosthetic less accessible, it still provides an exciting glimpse into the future of prosthetics for amputees.

However, for those who are unable to consider this advanced APL bionic arm, prosthetics such as the MiniTouch, recently described in nature, may be desirable. The MiniTouch technology allows the detection of temperature through prosthetic limbs without the need for surgery. The technology works similarly with temperature sensors on the prosthetic that deliver thermal information to the patients’ neurones through points on their skin. It can be attached to many different prosthetic limbs already on the market making it much more accessible to amputees.

Developments like these were unimaginable during the time of the Cairo toe indicating that the possibilities with prosthetics could be endless. One limb amputation happens every 30 seconds and there are over 2.1 million people living with a limb amputation in the US alone. Therefore, these advancements provide a promising glimpse into the future of prosthetic limbs with increased functionality and accessibility.

This is an excellent, well written blog. The narrative is engaging and easy to follow. It could be improved by being more reflective throughout. What did you learn while researching this topic? What surprised you? More referencing throughout would also be beneficial.