By Claire Reed, Doctoral Researcher

Attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, better known as ADHD, is a common neurodiverse condition experienced by 5-11% of children. It rarely comes alone- nearly 90% of people with ADHD have at least one other condition, ranging from asthma to anxiety to epilepsy. Diagnoses which more often occur together are called comorbidities. Our recent paper, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, explored another common comorbidity: obesity. Obesity increases the risk for other health conditions such as heart disease, liver disease and type 2 diabetes.

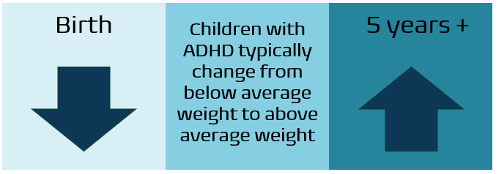

We already know that children with ADHD tend to be lighter at birth than children without ADHD, but that older children and adults with ADHD are more likely to have obesity. Our research aimed to pinpoint when this change happens. We were also interested to find out whether ADHD symptoms influence weight, if weight impacts ADHD symptoms, or if both affect the other.

We used data from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) which follows around 19,000 children born at the start of the millennium. Information about these children and their families has been gathered at 7 time points when children were between 9 months and 17 years old.

In line with previous research, we found that children in an ADHD group were on average lighter at birth than those in a control group without ADHD. By 9 months old, this difference in weight disappeared. However, from age 5, children with ADHD showed a higher likelihood of having obesity and this continued throughout childhood and the teenage years.

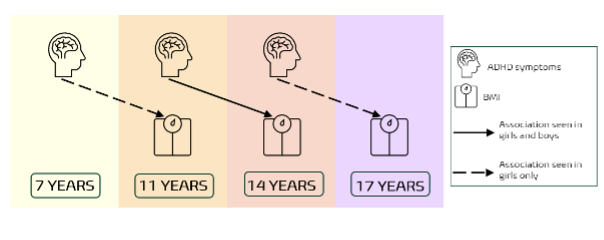

To get a clearer picture of how ADHD and weight are related, we looked at how ADHD symptoms and body mass index (BMI) influenced each other over time, examining boys and girls separately. Our statistical analysis controlled for environmental factors that could have an impact on weight or ADHD symptoms. We also controlled for the effect of medication as it can cause children to lose weight. Our findings differed for girls and boys. For girls, we found that higher ADHD symptoms at age 7 were linked to higher BMI by age 11. This pattern continued throughout adolescence with ADHD symptoms at one time point predicting BMI at the next. For boys, the association appeared a bit later and didn’t last as long. ADHD symptoms at age 11 were only linked to BMI at age 14. BMI however never predicted ADHD symptoms at the next time point in either boys or girls.

Some experiences before birth, called prenatal risk factors, can also lead to increased BMI. In our study, prenatal risk factors were indeed linked to higher BMI across ages. The risk factors included mother’s BMI, higher blood pressure, and smoking during pregnancy. The more risk factors a child had, the higher their BMI. ADHD symptoms only directly predicted later BMI from age 7, and not as strongly. This suggests that environmental, and possibly genetic, factors likely play a large role in the development of obesity, while a child’s ADHD symptoms play an additional role later in childhood.

While the pathways of how ADHD symptoms impact weight need to be clarified to make firmer recommendations, our results indicate that children with ADHD may have additional needs regarding learning about nutrition habits.

Reed, C., Cortese, S., Golm, D., & Brandt, V. (2024). Longitudinal Associations Between ADHD and Weight From Birth to Adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2024.09.009