The Neolithic

Prehistory and the Neolithic

Most European Prehistoric ditched enclosures were constructed during what is known as ‘the Neolithic’. The Neolithic is a period in the History of certain human cultures, and part of the so-called ‘Prehistory‘. Peoples from the remote past are conventionally called ‘Prehistoric’ when we only know about their existence, their ways of life and their behaviours, from non-written sources. At the time Prehistoric events took place, no written records were created, or at least no written accounts have survived until today. All we have is material remains of the activities performed in the past, such as ceramic vessels, lithic tools, buildings, graves and so on. For that reason, Prehistoric communities in general, and Neolithic human groups in particular, are a prominent object of study for Archaeology.

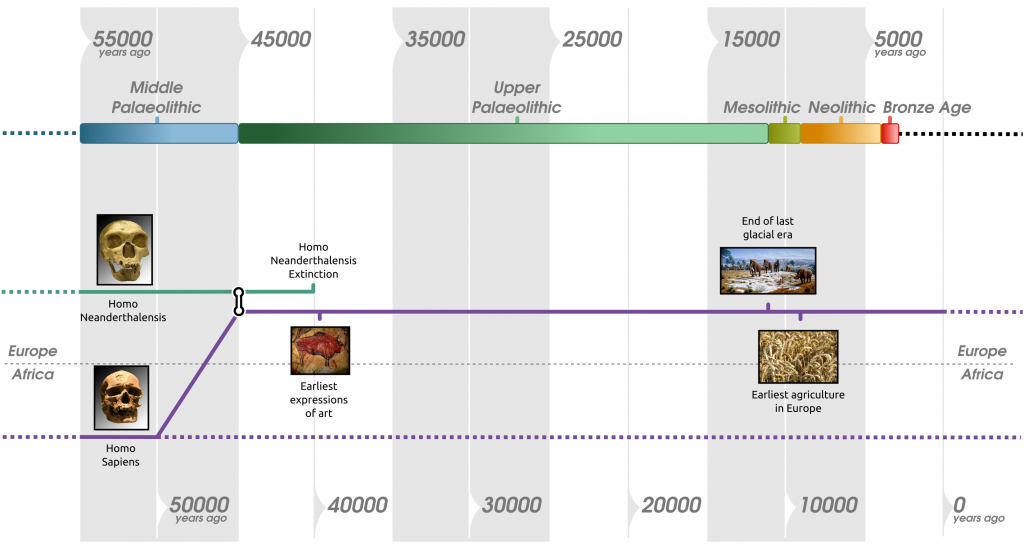

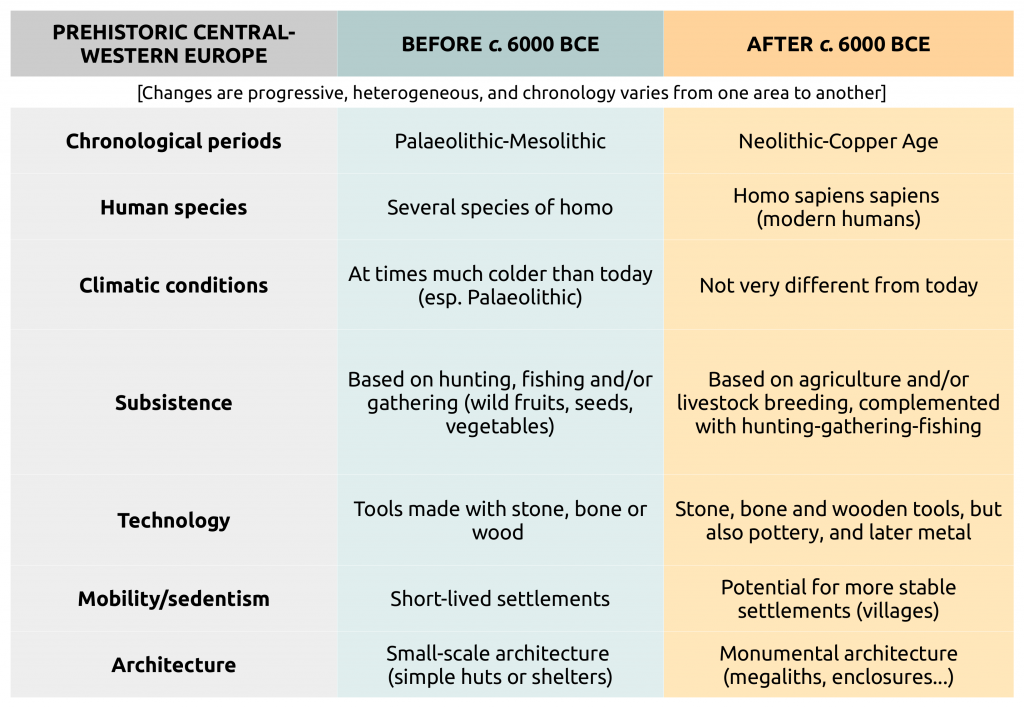

The Prehistory is divided in a series of periods or time intervals characterised by specific cultural features. Periods vary from one cultural area to another. For instance, Prehistoric periods established by archaeologists are not the same in Western Europe and Central America, because the cultural and historical trajectories of the peoples living in those areas were very different. The Neolithic is one of the later periods of Prehistory. Earlier periods, such as the Palaeolithic, may be determined by the existence of one or several human species in the context of processes of human evolution (e.g. homo habilis, homo antecessor, etc.). But in the Neolithic all human groups were anatomically similar to contemporary humans, and, like us, they are all considered members of the homo sapiens sapiens species.

The ‘Neolithic age’.

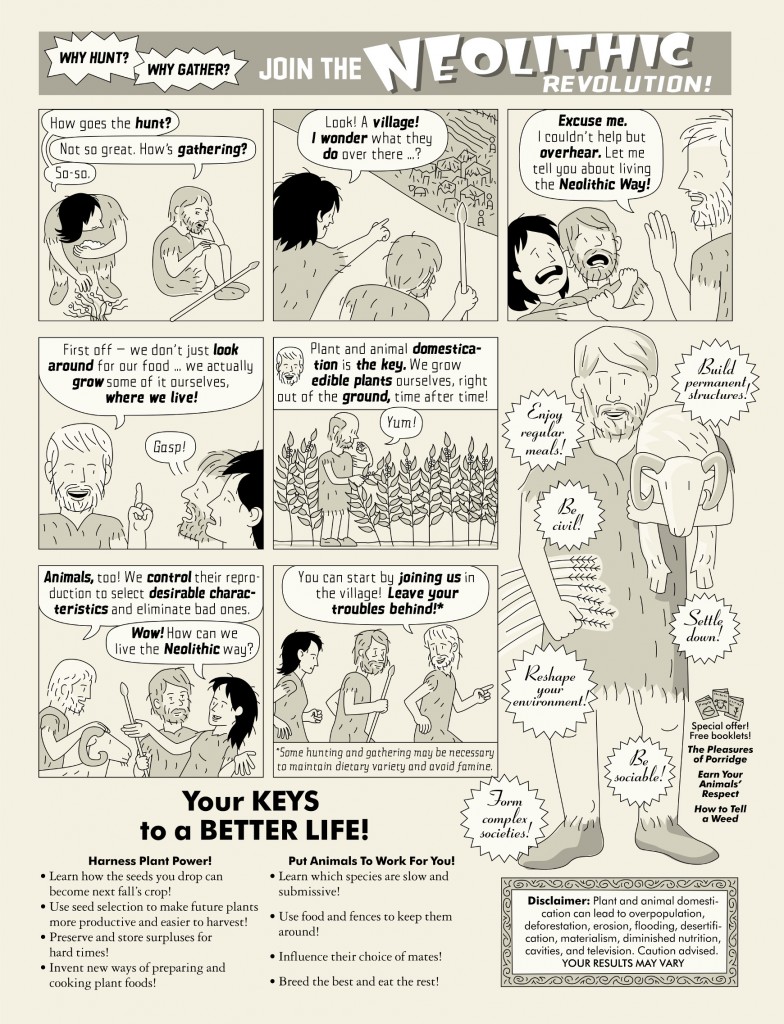

The Neolithic is a period of progressive but substantial changes. Traditionally, archaeologists have defined Neolithic communities on the basis of their use of new tools and technologies, a new economy based on agriculture and/or livestock breeding and on new ideas and behaviours. Before the Neolithic, all humans were hunter-gatherers. This mean that nature, as is, provided all they needed. They hunted and fished, and they gathered seeds, fruits, vegetables and seafood, but they almost did not have to transform or act upon nature to secure their existence. Their impact on the landscape was not much bigger than that of other animals. Importantly, they received immediate (or almost immediate) benefit from their economic activities: they could hunt or gather, and eat what they had hunted or gathered, on the same day. In those terms, the Neolithic, in its classic conception, is radically different, although it must be noted that changes were often progressive and heterogeneous.

Neolithic groups acted upon nature, transforming it, to get what they needed as regards food, clothes, tools, and the like. A good example is the domestication of plants and animals, which led to the physical (genetic) transformation of entire species, and the creation of new sub-species. How did humans manage to do something like that? This was achieved through selective reproduction: people selected certain individual plants or animals because they had qualities that benefited them. For example, docile animals, or tasty vegetables. Then they favoured the reproduction of individuals with those features over those which had less desirable characteristics. After several generations of selective reproduction, domesticated animals became more docile or more productive, and domesticated plants turned bigger, sweeter or more nutritive.

Agriculture and husbandry implied a change in the concept of work, as well. In the Neolithic, many economic practices did not have an immediate return: they were long-term investments of energy that could take months or even years to yield positive results. Partially because of this, Neolithic communities, and agrarian societies in particular, tended to adopt more sedentary, less mobile ways of life. Farmers got progressively attached to the land they worked on, settling and building less dynamic relationships with the landscape. In certain contexts, human began to live in dwellings built using more durable materials, or employing more sophisticated techniques. These dwellings, in turn, often clustered forming some of the earliest villages. This picture is obviously more complicated in the case of groups mainly based on livestock breeding, since they had to regularly move around with their animals, and for communities with mixed economies.

The introduction of agriculture and livestock breeding is often accompanied by changes in other facets of life, including beliefs, funerary practices, dwellings, tools and artefacts, etc. For example, the development of pottery favoured storage of food and resources in ceramic vessels. A more intensive and selective use of flint to make tools and prestige goods led to the emergence of the first mines. Neolithic peoples, as opposed to the earlier ones, also tended to adopt more formalised burial customs. Or perhaps they just did it in a way that left more archaeologically recognisable traces. Regardless, it is in the Neolithic when necropolises –that is, clusters of graves– began to be widespread, bringing about new forms of relationship between the living and the dead, between people and their ancestors.

Was the ‘Neolithisation’ a change for the better?

Most human groups living today experienced some kind of Neolithic transformation in the past. Their economy is based primarily on the consumption of domesticated plants and animals. This is because, relative to hunting-gathering strategies, the new economic forms have important advantages. Agriculture in particular is well suited when there is a need to increase economic production, usually due to a growth in population density. However, not all human communities have become Neolithic. Some contemporary peoples have traditionally based their economy on hunting, gathering and fishing, and continue to do so even in the 21st century. It is even possible that some communities will never become Neolithic as defined here at all. Why is this?

Under certain circumstances, the adoption of agriculture and husbandry does not make much sense. The hunting-gathering way of life has shown to be a very successful one, keeping communities alive (some would even say ‘happy’) from the Palaeolithic until today; that is, for hundred of thousands of years. At the same time, the effectiveness of agriculture, stock breeding and sedentism depends on many factors. The potential disadvantages are multiple. Among them, for instance, are: longer and harder working hours, less varied diets (mainly based on the ingestion of carbohydrates), more risks (bad weather, pests, fire, etc.), and more diseases. In short, despite its indisputable virtues, in certain situations the adoption of Neolithic practices may not be such a good idea.

Origins and expansion into Europe of Neolithic things and practices.

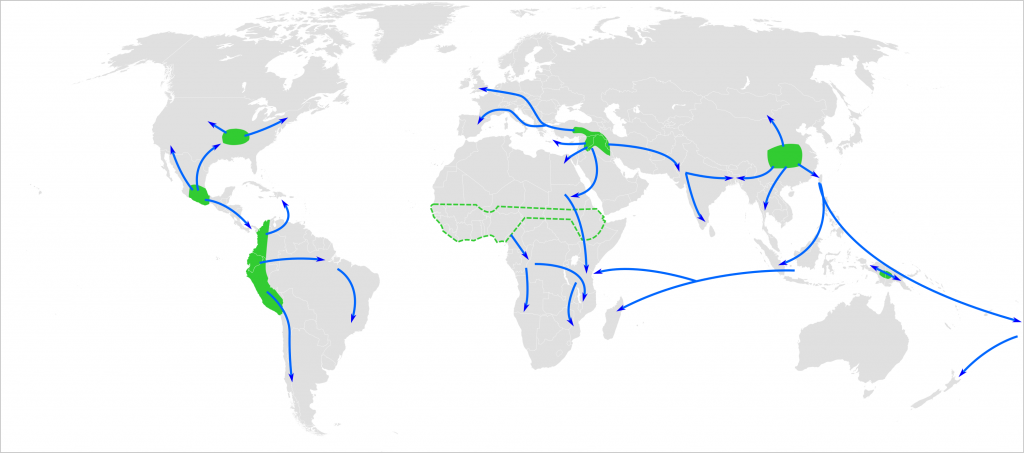

When considered at a planetary scale, the practices commonly associated with the Neolithic appeared independently in certain regions at different times. As far as the Old World (Eurasia and Africa) is concerned, Neolithic practices (agriculture, husbandry…) and things (ceramics, polished stone tools…) emerged in South-West Asia, not far from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, around 8500 BCE. That is roughly 10500 years ago. From there, they somehow spread through the movement of peoples and/or ideas into Africa and Europe.

The earliest evidence of Neolithic activities in Central and Western Europe date back to 6000-5500 BCE, about 8000-7500 years ago. The question of how and why Neolithic things and practices reached all of Europe from South-Western Asia is one of the key debates in the discipline of Archaeology. We will not get into details here. Suffice to say that some of the animals and plants that would later become domesticated were not available naturally in most European regions before the Neolithic. This means that they must have come from the Near East somehow. Throughout the decades, discussions have been centred on the specific mechanisms of this process. Was there a colonisation, that is, a movement and settlement of people, from the Eastern Mediterranean area into Central, and later, Western Europe? Was it just a transmission of ideas and artefacts, with no significant movement of peoples, instead? How did Neolithic things and practices arrive in the Western Mediterranean? What was the role of ‘indigenous’ Mesolithic communities in all this? These and other questions remain open and the debate is very much alive today.

After the Neolithic: the Copper Age in Europe.

In some areas of the planet, such as South-West Asia and parts of Europe, the Neolithic is followed by what is known as the Copper Age or Chalcolithic, a ‘transitional’ period between the Neolithic and the so-called ‘Bronze Age’. Originally, the term ‘Chalcolithic’ referred to the invention and spread of metallurgy. This new technology allowed prehistoric communities to make metallic tools instead of simply working with lithic (also wood, bone) artefacts, as was the case in the Neolithic and earlier. Metallurgy, invented somewhere between Eastern Europe and Western Asia, slowly spread amongst European groups, influencing social and symbolic practices at the end of the Neolithic and in the Copper Age.

However, nowadays the Copper age is more commonly defined on the basis of social, economic and symbolic changes. In most accounts, it is associated with a process of progressive intensification of economic production, demographic growth, increasing inter-community exchange of raw materials, tools and products, and a higher level of social complexity. In the ‘Bronze Age‘ of the Old World, these trends went even further. It was then when the earliest cities and state societies appeared in places of South-West Asia, Egypt and others.

Next: megalithic worlds