Berit Fischer (http://www.beritfischer.org), a recent WSA PhD graduate, is curating an exciting three-day live online event (10-12 Dec 2020), Liminal Encounters. Details are below; registration and full details of the programme are at this link.

WINCHESTER SCHOOL OF ART

Berit Fischer (http://www.beritfischer.org), a recent WSA PhD graduate, is curating an exciting three-day live online event (10-12 Dec 2020), Liminal Encounters. Details are below; registration and full details of the programme are at this link.

Ana Čavić, currently a WSA PhD student, below discusses her artwork, ‘Rules that order the reading of clouds’, exhibited by the Intermission Museum of Art.

John Beck & Ryan Bishop Technocrats of the Imagination, recently published by Duke University Press, is about a particularly striking form of interdisciplinarity: the Cold War cooperation between the military-industrial complex and avant-garde art. Below, Ryan shares some of the background related to how he came to co-author the book, the experience of writing the book and the continued necessity of understanding the Cold War.

The right to look is not about seeing. It begins at a personal level with the look into someone else’s eyes to express friendship, solidarity, or love. That look must be mutual, each person inventing the other, or it fails … It is the claim to a subjectivity that has the autonomy to arrange the relations of the visible and the sayable. The right to look confronts the police who say to us, ‘Move on, there’s nothing to see here.’ Only there is, and we know it and so do they.1

Bevis Fenner

14 June 2016

The June session of the Phenomenology and Imagination Research Group took our previously explored idea of conversation as methodology on a slight detour. To be precise, that detour took the group to West Dorset via my narrative retelling of a recent four week residency as part of Anna Best’s Mothership Residencies project. I used the session to open up the notion of conversation to the possibilities of collaboration both with humans and non-humans. Drawing upon Deleuze and Guattari’s ideas of affects and becoming, and Karen Barad’s explorations of human and non-human agents, I set out to start a conversation about the nature of conversation and collaboration in the art-site relations of the artist’s residency. The reading I sent the group prior to the session was a chapter on residency and collaboration from For Creative Geographies (2014) by Harriet Hawkins – an exploration of the human interactions and encounters that residencies can produce, as well as the ways in which material making and skill-sharing can build community and transform individual and collective subjectivities. Here, person-site relations become part of an affective praxis in opposition to alienating and dehumanising effects of neoliberalism – individualism, competitiveness, exchangism, deskilling, social atomisation and so on. Hawkins stresses the importance of shared labour – literally collaboration – in transforming individual and collective consciousness. She uses gardening – a key aspect of my residency – as an example of a ‘grounded’ practice that has the power to disrupt and reconfigure the habitual relations of everyday life:

“We could suggest that the physical, discursive, and haptic experiences of shared labour… was part of the creation of a rupture in everyday practices from within which new identities and shared consciousness could emerge (Hawkins, 2014: 170)”.

The starting point for the group’s conversation was a discussion of the unique labour relations of the residency, which as I admitted to the group, were an initial source of suspicion as I adopted the cynical post-human perspective of trying to analyse the power relations between host and guest and the exact terms of labour exchange. However, in attempting to calculate and quantify these relations, I found that rather than reflecting the neoliberal idea that altruistic acts are often thinly veiled opportunism and that everyone is ultimately self-serving, the residency provoked a sense that the reciprocal nature of the collaboration had far more humane dimensions. It seemed that the more I tried to quantify the exchange, particularly in relation to labour value because I was not paying money to be there, the more the things shattered to reveal human truths and a qualitative value way beyond any kind of contractual arrangement. Thus my attempts to provoke a breakdown of assumed neoliberal labour relations were unjustified as the layers fell away to reveal a very human conversation about not only the need for people to live together but also the importance of bringing things together that are usually held apart. Instead of finding an illusionary micro-utopia sustained by wealth and privilege, which masked true power and property relations, I found a situation of honesty – a genuine attempt to make new worlds and recuperate old ones. Small-scale organic farming is an uphill struggle where the old binaries of humans pitted against nature are initially reinforced. However, in responsible and ethical engagement with complex ecosystems, culture / nature binaries are eroded. Pestilence ceases to become a non-human enemy to be wiped out with petrochemicals when ecosystems are in balance. The context for the residency was not only thought-provoking but also provided a space for dialogue between humans and non-humans alike – “a potential space for collaborative thinking”, as Noriko put it. One of the key things that came out of the session was the notion of ‘maternal space’ – of how, out of necessity, things of difference are brought together. Instead of seeing disruptions as inconveniences that break our ‘trains of thought’, by being open to ‘external’ factors and intrusions we are able to open out to new and emergent ways of being and seeing that foster generative creative processes. My challenge was to move beyond provocation as a means of ‘exploding’ power and property relations, and to embrace collaborative conversation as a means of gently unpicking the complexities of context without ignoring tensions and differences. In the words of Harriet Hawkins (2014), to develop truly collaborative art-site relations we must ‘remain open to the generative complexities of a given site… to be able to recognise the problematics of context, without sacrificing the ability to work productively within the community…’ (Hawkins, 2014: 166).

Hawkins, H. (2014). For Creative Geographies: Geography, Visual Arts and the Making of Worlds. London: Routledge.

Yvonne Jones

09 May 2016

Having considered Material Imagination within the group, I wanted to consider Non-Material Imagination (my words). Is there a connecting line of thought between the received image, memory and imagination, and, by implication, the mind / body interoperations? Through looking at several writers, I am asking how are the ideas related, do they interlink, overlap? Is there one indescribable that they speak of, do any of them support each other, can they be developed into a position where the non-material imagination becomes visible, and what, if it does, is the significance for living human beings today?

Bachelard speaks of images of matter, direct experience of matter, and images of form.

Imagination comes before all else, material imagination and the poetic image reverberate with the human, (go beyond data and form). Images of form are perishable, vain images and the becoming of surfaces.(Bachelard; Poetics and Reverie 1971, Poetics of Space 1969)

Descartes states ‘in infancy our mind was so tightly bound to the body as not to be open to any experience (cogitationbus) except mere feelings of what affected the body’. He creates a dualism and divide between mind and body suggesting ‘In adult life the mind is no longer wholly slave to the body and does not relate everything to that’. (Anscombe and Geach, 1954, Descartes Philosophical writings, extracts from Principles of Philosophy part 1 First Philosophy.R. LXXl, p. 196).

Lacan speaks of the Real, The Imaginary Order and Symbolic Order. Of the Real, Cussans believes it is increasingly difficult to experience, and is now only approached through trauma. He holds that the cinema was the beginning of the end of Real. (Symbolic Wounds and the Impossible Real – The Paradox of Traumatic Realism in Televisual Representations of Terror. 2003 lecture at WSA).

Steve Dixon tells us ‘The bifurcatory division between body and mind has lead to an objectified redefinition of the human subject – the ‘person’ – into an abstracted, depersonalised and increasingly dehumanised physical object.’ (Dixon, S. 2003, Adventures in Cybertheatre. IN ZAPP, A. & BERG, E. (Eds.) Networked Narrative Environments as imaginary spaces of being, Liverpool 23rd May 2003. Liverpool, FACT in association with MIRIAD/ Manchester Metropolitan University).

Moravec foretells there will be very few original experiences, (in time to come) they are mostly held as data in a huge computer ‘out there somewhere’, offering us the raw cold data of “experiences” had over the generations. (Moravec. 1997, The Senses have no Future)

Makedon states “Without a World to imagine about, there would be no-thing imaginable… that even an “impossible” world is only imaginable within the context of ‘possible imaginings’ provided by the world humans has learned about.

Unpicking aspects of the above and bringing in Garry and Polaschek (Imagination and Memory. 2000) and, Bergen, Narayan and Feldman (Embodied Verbal Semantics: Evidence from an Image-Verb Making. 2003) it opens the possibility that mind operations are not suitably evolved to clearly and reliably distinguish between images that are materially present and those that are represented to it via non-material images, photography, film, video, internet content.

This could prove an issue going forward.

Yonat Nitzan-Green

04 April 2016

Text for group’s discussion: ‘”Matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns and remembers” Interview with Karen Barad’, (from “Meeting Utrecht Halfway” intra-active event, June 6, 2009, at the 7th European Feminist Research Conference, Utrecht University).

‘In the imagination of each of us there exists the material image of an ideal paste, a perfect synthesis of resistance and malleability, a marvellous equilibrium between accepting forces and refusing forces. Starting from this equilibrium, which gives an immediate eagerness to the working hand, there arise opposing pejorative judgments: too soft or too hard. One could say as well that midway between these contrary extremes, the hand recognizes instinctively the perfect paste. A normal material imagination immediately places this optimum paste into the hands of the dreamer. Everyone who dreams of paste knows this perfect mixture, as unmistakeable to the hand as the perfect solid is to the geometrician’s eye.’

Gaston Bachelard, On Poetic Imagination and Reverie, 2005, p. 81.

This session opened up with a performative act, entitled ‘10 minutes of making Tahini’. The participants were given all the right ingredients, however only one instruction as to how to make tahini. The intention was to bring to light the dialogue between artist and material. In Bachelard’s words: ‘…there arise opposing pejorative judgment: too soft or too hard.’

Both, Bachelard’s quote and this performative act served as an invitation to engage in an interview with Physicist feminist Karen Barad in which she explains her theory of ‘agential realism’.

According to Barad ‘agential realism’ is part of relational ontologies. Agency is ‘about response-ability’. It ‘is not something possessed by humans, or non-humans … It is an enactment. … it enlists … “non-human” as well as “humans.”’ Entanglement is the consideration of meaning and matter together which questions the dualism nature – culture and the separation of ‘matters of fact from matters of concern (Bruno Latour) and matters of care (Maria Puig de la Bellacasa)’. The notion of intra-action is called for in order to re-think causality. ‘Causality is not interactional, but rather intra-actional.’ By this Barad means that causality is a process of emergence rather than a game of billiard balls: ‘Cause and effect are supposed to follow one upon the other like billiard balls … causality has become a dirty word.’ Barad invites us to find new kinds and new understandings of causalities.

Barad developed diffraction as a main concept in her theory, as a practice and a methodology. She expands the classical physics definition of diffraction, by understanding this metaphor through quantum physics. On the one hand, ‘Geometric optics does not pay any attention to the nature of light … it is completely agnostic about whether light is a particle or a wave…’. On the other hand, understanding diffraction by using quantum mechanics ‘allows you to study both the nature of the apparatus and also the object’. This, she claims, is ‘not just a matter of interference, but of entanglement, an ethico-onto-epistemological matter.’

Noriko Suzuki-Bosco

07 March 2016

The reading material selected for this PIRG session, ‘New Bachelards?: Reveries, Elements and Twenty-First Century Materialism’ by James L. Smith, looked to understand some of the cross resonance between the philosophy of Gaston Bachelard and the materialism of the twenty-first century. Smith brought together Bachelard’s philosophy on the interpretation of elements, the poetics of reverie and material imagination with Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things by Jane Bennett (2010) and Elemental Philosophy: Earth, Air, Fire and Water as Elemental Ideas by David Macauley (2010). The investigation into a new Bachelard emerging from the synthesis of ideas that engaged with a more ‘diffuse, more complex, network of images, an ecological awareness and an ethic of conservation’ (Smith 2012, 165) provided an engaging backdrop for our discussions around material, making and thinking.

According to the emerging trend of new materialists thought, matter is no longer considered to be inert but to hold transformative qualities to be ‘agentive, indeterminate, constantly forming and reforming in unexpected ways.’ (Hickey-Moody and Page 2016, 2). Bennett’s theory of ‘vibrant materialism’ also reinforces the idea that matter as ‘passive stuff, as raw, brute or inert’ is no longer applicable but instead ‘an ability to feel the vitality of the object, be it with the reason or the body, gives the option of a political engagement with the world that avoids deadening or flattening objects or reducing nature to utility.’ (Smith 2012, 158)

The power of matter to exert influence over the human subject makes us reconsider the agential properties of elements. Bennett argues for a world of ‘intimate liveliness and distributed agency’ where human interaction with matter that has ‘affect, bahaviour, vitality and agency’ questions the human-centric theories of action (ibid, 158). In a world such as this, agency is not solely the province of humans but as something that emerge through the configuration of human and non-human forces.

Theoretical physicist and professor of feminist studies Karan Barad’s theory of ‘agential realism’ also echoes the idea of distributed agency. According to Barad, ‘agency is about possibilities for worldly re-configurings’. Agency, therefore, ‘is not something possessed by humans or non-humans but is an ‘enactment’’ (Dolphijn and van der Tuin 2012, 56). Agency, for Barad, is something that emerges through the process of ‘intra-acting’, a term introduced by Barad to conceptualize the action between matters and to propose a new way of thinking causality.

The ‘object-oriented’ philosophy, where matter has power to hold and shape how humans perceive and interact with the world provided context for lively discussion to take place and during the session, we touched on other areas of theory such as Deleuze and Guttari’s idea of ‘whatness and thingness’ (‘A Thousand Plateaus’), the affect theory, Merleau-Ponty’s theory of affordance, Heidegger’s notion of ‘handling’ and ‘understanding’ (‘The Questions Concerning Technology’) as well as feminist theories, namely that of Julia Kristeva and Elizabeth Grosz (‘Volatile Bodies’). Furthermore, contemporary geographical studies were mentioned as reference points to reflect on how our environmental perceptions (how we connected with the world of material stuff) may also be affected by the ways we interact with the material matters of the world.

The discussion developed into thoughts around embodied learning through material pedagogy and ‘material thinking’ (to borrow Paul Carter’s term). According to Hickey-Moody and Page, material pedagogy and materials thinking do not look at learning as a passive process of simply acquiring information but instead conceives learning to be a ‘relational process where theory is entangled with everyday practice’ (Hickey-Moody and Page 2016, 13). Learning through material thinking points to a process of ‘becoming’ through the relational interaction of body and matter, which is different from understanding using cognitive faculties.

As research artists, the idea that materials are not just passive objects to be used instrumentally by artists, but rather the materials and processes of production have their own intelligence that come into play to interact with the artists’ creativity, resonated with all of us and the session concluded with a small collaged postcard-art making workshop in an attempt to ‘join the hand, mind and eye’ (Carter 2004, xiii).

Whilst choosing the materials for the collage, everyone was asked to be conscious about the way they chose the images and handled the materials. We spent around twenty minutes to create the small artworks which was followed by a presentation of the works around the table and a short discussion. The presentation revealed interesting insights into how the artist’s mind worked during the process of making. Intuition seemed to be backed up with certain habitual characteristics for choosing colours and textures of the materials as well as how they were physically handled.

Studies around new materialism and material thinking offer rich grounds to think about our relationship with the material world around us. As we learn more about the world that surrounds us, we proceed to learn how to better correspond with it. As Tim Ingold emphasizes, ‘the mind is very much connected with the body where the thinking corresponds to what is happening to the material.’ (Ingold 2013, 7). The potentials of relational interaction between human and non-human matter that new materialists draw out are exciting perspective to broaden and transform our sense of Being in the world.

References (including materials mentioned during the meeting)

Barad, K. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Berberich, C., Campbell, N. and Hudson, R. (eds), Affective Landscapes in Literature, Art and Everyday Life: Memory, Place and the Senses, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015.

Best, S. Visualizing Feeling: Affect and the Feminine Avant-garde, London: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Carter, P. Material Thinking: The Theory and Practice of Creative Research, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2004.

Crouch, D. Flirting with Space: Journeys with Creativity, Burlington: Ashgate, 2010.

Deleuze, G. and Guttari, F. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, London: Althorne Press, 1988.

Dolphijn, R. and van der Tuin, I. New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies, Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2012.

Gauntlett, D. Making is Connecting: The Social Meaning of Creativity from DIY and Knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011.

Grosz, E. Volatile Bodies, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Hawkins, H. For Creative Geographies: Geography, Visual Arts and the Making of Worlds, London: Routledge, 2014.

Hawkins, H. Geographical Aesthetics: Imagining Space, Staging Encounters, London: Routledge, 2015.

Heidegger, M. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, London: Harper and Row, 1977.

Hickey-Moody, A. and Page, T. Arts, Pedagogy and Cultural Resistance: New Materialism, 2016.

Ingold, T. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, 2013.

Macleod, K. and Holdridge, L. ‘The Enactment of Thinking: The Creative Practice Ph.D’ in Journal of Visual Art Practice vol. 4 no. 2 and 3, 2005.

Preston, J. Performing Matter: Interior Surface and Feminist Actions, Baunach, Germany: Spurbuch Verlag, 2014.

Smith, J. ‘New Bachelards?: Reveries, Elements and Twenty-First Century Materialism’ in Altre Modernità (Other Modernities), Numero Speciale Bachelard e la Plasticità della Materia, 2012, pp.156-167.

Jane Birkin is a former doctoral candidate at Winchester School of Art, completing her practice-based PhD in June 2015. Her essay ‘Art, Work, and Archives: Performativity and the Techniques of Production’ was recently published in Archive Journal.

This essay attempts to address the significance of my longstanding working connection with image collections and archives. It explains how aspects of archival thinking permeate the practices of various artists (including my own), notably through the application of performative working methods that position their work within an established genre of indexing and categorisation.

Performativity is defined here as a two-step procedure: firstly the making of an instruction, and secondly the following of that instruction. This is at odds with the early designation by J.L. Austin, in How to Do Things with Words, where the ‘saying’ and the ‘doing’ are one and the same thing. It also avoids the theatrical aspects that are often associated with performance art.

The call for papers was on the theme of ‘Radical Archives’, and asked what this well-used term really means. The ‘radical’ that is so often perceived in relation to the archive in terms of radical content (punk archives and so on) is here differently defined through archival cataloguing techniques of ordering, description and listing. In the way of the ‘readymade’, these institutional techniques become radicalised through their passage into art practice. The use of archival description in relation to the photographic image (the subject of my PhD thesis) constitutes a radical form of writing and reading the image, at odds with traditional hermeneutical analysis. It is an indexical rather than a representational approach, consistent with the recent material turn in photographic studies that is becoming a critical methodology in theory, practice and education, and frequently with reference to the ‘archived’ image.

Read the essay here:

Art, Work, and Archives: Performativity and the Techniques of Production

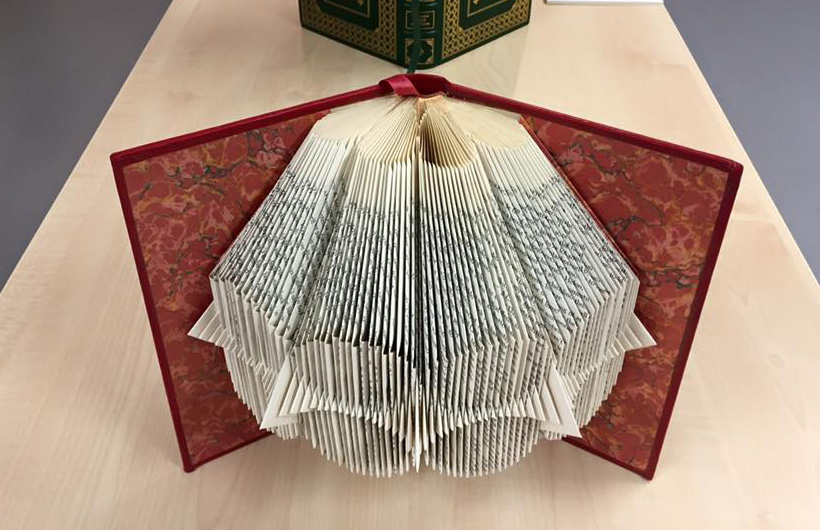

The exhibition, Reading Room: Leaves, Threads and Traces (November 2015), exhibited book art originally shown in Delhi and at the Colombo Art Biennale, Sri Lanka (2014) and Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India (2014). Working in collaboration with Blueprint 12, these shows were curated by Amit Jain, joined staff and students at Winchester School of Art for the seminar and the installation of works. The original shows of ‘Reading Room’ featured works by fifteen artists from across the world. Many of these works were shipped over for a new iteration of the show, and which were brought into dialogue with a selection from the Artists’ Books Collection held at the Winchester School of Art Library, which comprises book art from the 1960s to the present day. The seminar will be co-convened by Sunil Manghani, Amit Jain, August Davis, and Linda Newington.

As the final wall text produced for the show explains:

In placing items from the School’s own collection alongside the visiting collection of book art from South Asia, the themes of leaves, threads and traces are explored. It brings to the fore both the physicality of books – their material properties and relationship to material culture – and an imagination of books. This edition of Reading Room opens up how we interleave, draw together and re-trace thoughts, beliefs and emotions within the boundaries of a book and the cultures in which they circulate.

Preliminary curatorial decisions, such as the objects to be made available for display, had already been made in lead up to the installation of the show. However, the all-important positioning of the objects, the handling of the space, and the ‘journey(s)’ laid out for the viewer – the exhibition making as a practice – was to be carried out by the postgraduate research group in just three days. Amit Jain, who had curated the two previous exhibitions and brought the books over from India, purposely played little part in the decision-making processes. He was interested to see how his exhibitions would be re-made, and how he would himself learn from the process. Amit made it clear from the start that the final exhibition, whatever shape it was to take, could never be perceived as a failure in either curatorial or pedagogic terms, but that the processes of making and juxtaposition, and the subsequent viewing by the public, would serve as a practical site of learning. Like all the events in the re:making series, this was designed as a collaborative and experimental task for PhD students; it was to be an intensive project that would thoroughly test the proposition of thinking through making that is key to this seminar series.

The book is a mini exhibition space in itself: it has content and it has a physicality and a three dimensional space through which to navigate this content. Reading Room could be perceived then as an exhibition of interrelating exhibitions—a difficult and interesting curatorial notion to begin with. As we all know, the navigation of both books and exhibitions is not always linear, it is a complex back and forth interaction, often with multiple visits to certain parts. In this limited time, a coherent exhibition had to be installed that would expose commonality and create a dialogue between the two different collections, yet would still allow an openness of conditions so that the visitor/reader would be able to traverse the display in their own way and to make their own connections.

As with all exhibitions, logistics around the objects and the space in which they are to be displayed play a large part in the decision-making around display. The extremely delicate nature of a number of the objects meant that they could not be truly navigated at all, but were displayed as static objects that denied the visitor the haptic interface usually associated with the book. Happily, some objects could be touched and used as books; indeed they actively required handling in order to explore their methodology and message. Other objects were not books as we commonly experience them at all, but book-related artworks in different forms. These were conceptual pieces, some of a highly political nature, with temporal qualities (usually experienced through page turning) here embodied and understood through the varying and openly exhibited processes of their making.

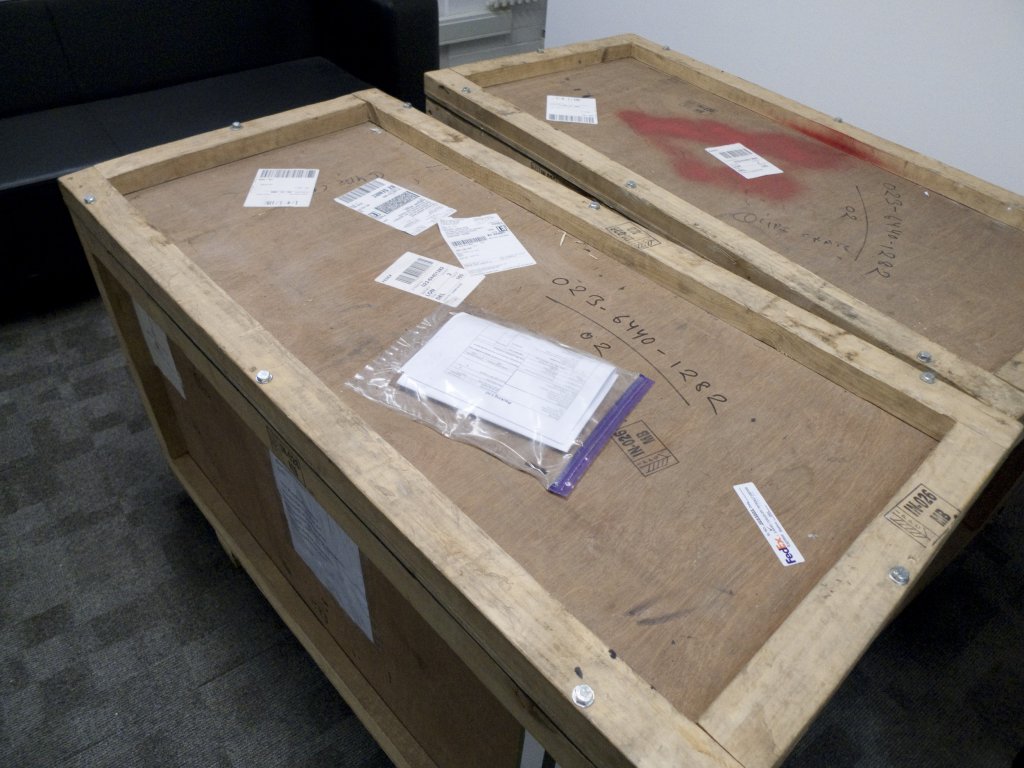

Before the books were even unpacked, systems of good practice had to be formulated that would ensure the safe handling of the objects, and some background information on the objects had to be relayed and considered. It was late on Day One before the fascinatingly inaccessible packing cases were opened and the books from India were uncovered and laid out. For the group this was at the same time a contemplative act of revealing and an abrupt realisation of the task ahead.

Before the books were even unpacked, systems of good practice had to be formulated that would ensure the safe handling of the objects, and some background information on the objects had to be relayed and considered. It was late on Day One before the fascinatingly inaccessible packing cases were opened and the books from India were uncovered and laid out. For the group this was at the same time a contemplative act of revealing and an abrupt realisation of the task ahead.

The three days of installation were peppered with periods of notional inactivity, weariness and even boredom. But these lulls were actually active times of information processing (such times play an important part in all making projects) and they undoubtedly played a significant part in the successful, intelligent and articulate final installation of the show. The act of unpacking that was so physically experienced by the group could be viewed metaphorically as a critical part of the thinking through making process.