3D printing is now commonplace, and frequently referred to in popular discourse. Controversies arise with the 3D printing of illegal items, such as a working model of a gun, or utopian visions unfold with ideas of 3D printing buildings and aircraft. It is also the case that 3D printing is now increasingly affordable and accessible. However, unless you have had first hand experience of the production of 3D printing there remain many questions and quandaries. The second of the Re: Making seminars, under the title of Plastic Surgery, sought to address this knowledge gap. The two day seminar was primarily led by Ian Dawson (who has many years of experience as a sculptor) and Chris Carter (who regularly teaches many sculptural techniques, including the use of 3D printing). But it was also a collaboration with Sunil Manghani, who introduced the two days and offered a specific ‘prompt’, bringing in plastic toys of Michael Jackson and Kylie Minogue.

The choice of these two figures was on the one hand simply for their associations as icons of ‘plastic pop’. Manghani began by discussing notions of plasticity as it is used in the arts. The term ‘plastic arts’ is perhaps less used now. It refers of course to 3D art, typically as sculpture or bas-relief, that is characterised by three dimensional modelling. However, as a plural term, it was often used to refer also to visual art (as painting, sculpture, or film), and especially as a means to distinguish from ‘written’ art forms (as poetry or music). However, the relationship of plasticity and writing was asserted in the seminar through reference to Roland Barthes’ classic text Mythologies. Originally published in 1957, the book offers short essays on the newly emerging consumer culture, which, postwar, is beginning to grow rapidly, and not least due to new, modernist technologies and processes including plastic. Indeed, one of the entry by Barthes is prompted by a plastics exhibition fair.

Despite having names of Greek shepherds (Polystyrene, Polyvinyl, Polyethylene), plastic … is in essence the stuff of alchemy. […] more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible. And it is this, in fact, which makes it a miraculous substance: a miracle is always a sudden transformation of nature. Plastic remains impregnated throughout with this wonder: it is less a thing than the trace of movement. […] In the hierarchy of the major poetic substances, it figures as a disgraced material … it embodies none of the genuine produce of the mineral world: foam, fibres, strata. It is a ‘shaped’ substance: whatever its final state, plastic keeps a flocculent appearance, something opaque, creamy and curdled, something powerless ever to achieve the triumphant smoothness of Nature. But what best reveals it for what it is is the sound it gives, at one hallow and flat; its noise is its undoing, as are its colours, for it seems capable of retaining only the most chemical-looking ones. […] Plastic is wholly swallowed up in the fact of being used: ultimately, objects will be invented for the sole pleasure of using them. The hierarchy of substances is abolished: a single one replaces them all: the whole world can be plasticised, and even life itself since, we are told, they are beginning to make plastic aortas. (Roland Barthes, ‘Plastic’ in Mythologies).

It is not just the emergence of plastic as a new material technology that is significant. Mythologies is a key text for the emergence and popularity of Semiology, or the science of the sign. Barthes’ innovation is to lift a concept related to language and linguistic and apply it not only to literature, but also popular culture. Everything is a ‘myth’ and ‘sign’ according to Barthes. As a cultural theory, semiotics, and later the notion of the Text (and intertextuality) thus opens up a whole new ‘plasticity’ of ‘reading’ culture and making meaning within it.

The choice of Michael Jackson and Kylie Minogue is undoubtedly a playful one, but of course connects immediately with the both the ‘trace of movement’ and the hallow and the flat that Barthes refers to with plastic. Jackson was certainly much discussed for this ‘plastic surgery’ (including of course the controversial debate about his skin tone). However, also, his music offers a means for his body to movement in ways that were not seen before (at least not in popular forms). His mooonwalking is the most obvious example, but more generally, his body is a highly fluid and yet sharp ‘medium’ through which he performed. As part of the seminar the video for his Smooth Criminal was screened, which includes a dramatic sequence in which he appears to lean forward beyond the realms of ordinary physics. The plastic model used for the seminar represents Michael Jackson from this video, and even comes complete with various re-attachable hands and feet and a ‘shadow’ stand that allows the figure to lean impossibly forward. The hard plastic of the figure offers a precision rendering of Jackson from his video, which in turn leant itself well to its reproduction through 3D scanning and clay moulding.

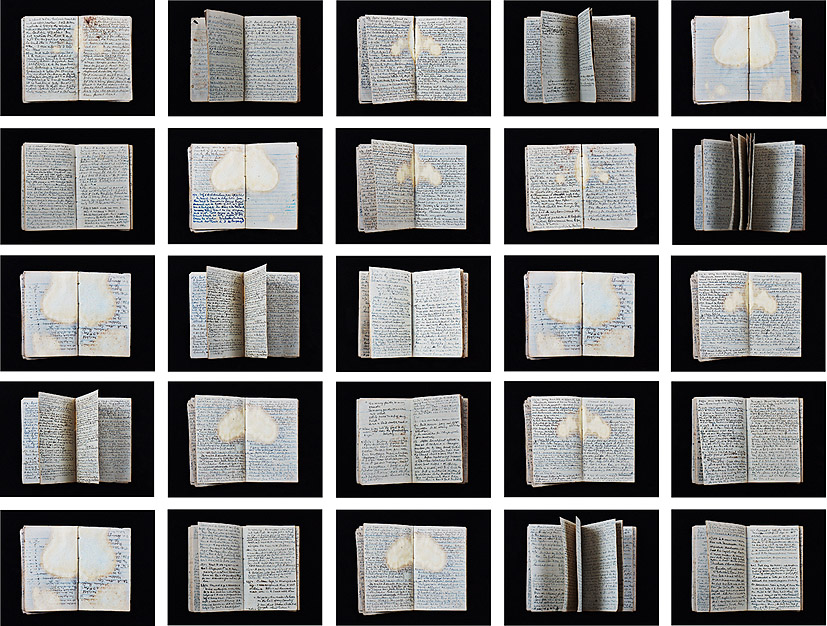

By contrast, a more rubbery doll of Kylie Minogue provided a fairly poor reproduction of her image. Which, in this case, was meant to recall her look c.2001, much associated with her worldwide hit ‘Can’t Get You Out Of My Head‘. The music critic Paul Morley has written a whole book around this video, Words and Music, which begins by making a bold connection between Minogue and Alvin Lucier’s 1969 work ‘I’m Sitting in a Room‘. Morley fascination with Kylie is of a virtual and near-alien creature. In ‘Can’t Get You Out Of My Head’, she drives effortlessly towards a Ballardian cityscape, the epitome of postmodern pop. During the seminar, a connection was also made to Allen Jones’ pop art, and particularly some of his drawings which develop his play of both bodies and clothes (and genders). Kylie Minogue perhaps represents the other side of digital pop music, with Michael Jackson representing last days of analogue music making. They become intro and outro of form of pop music that is ‘perfected’ by the late 1990s, to the point of sounding hallow and flat. An additional reason for the reference to Kylie Minogue came through Manghani’s drawing that was originally exhibited at the Practices of Research exhibition, and which was directly related to an entry he contributed to a book reimagining Roland Barthes’ Mythologies (see more). Thus, taken together, the kitsch dolls of Michael Jackson and Kylie Minogue were adopted as ‘models’ to explore simultaneously both physical 3D rendering processes and conceptual understandings of plasticity as evoked by the fine arts and cultural critique.

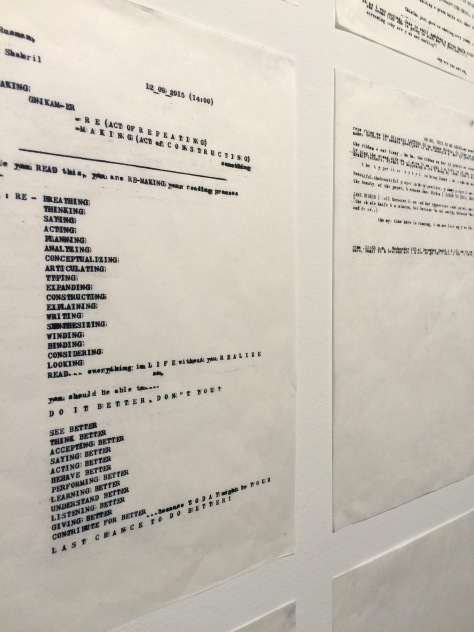

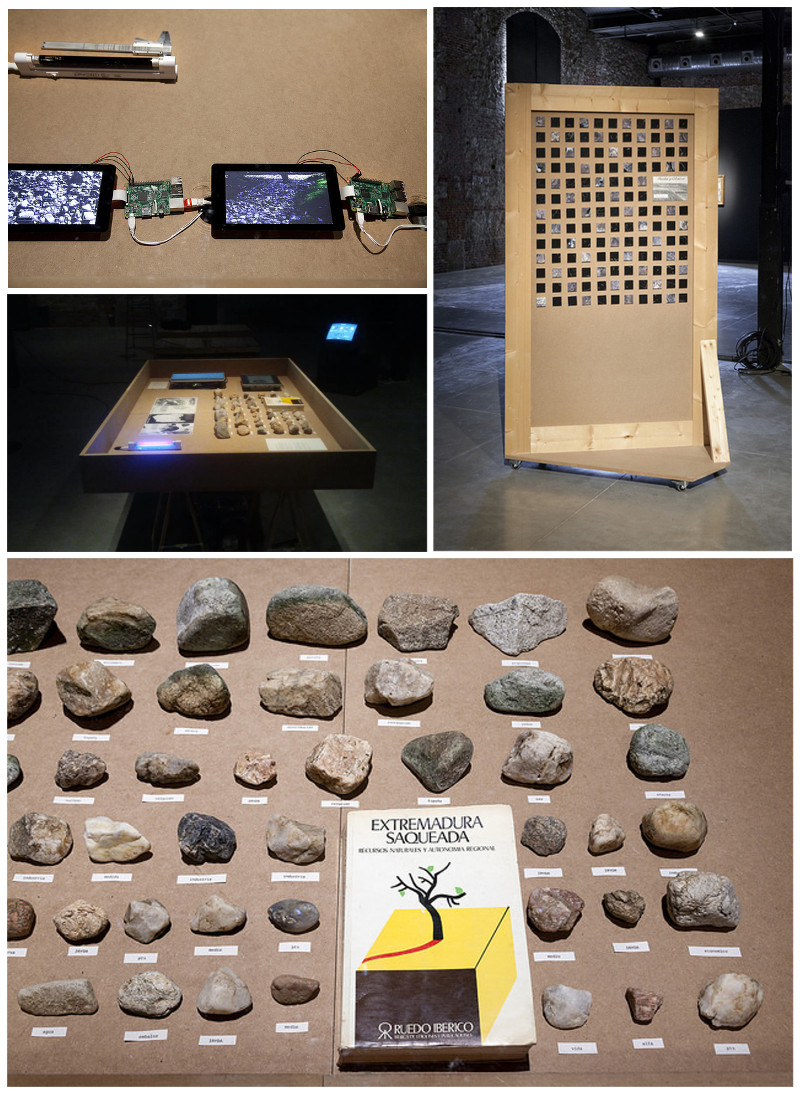

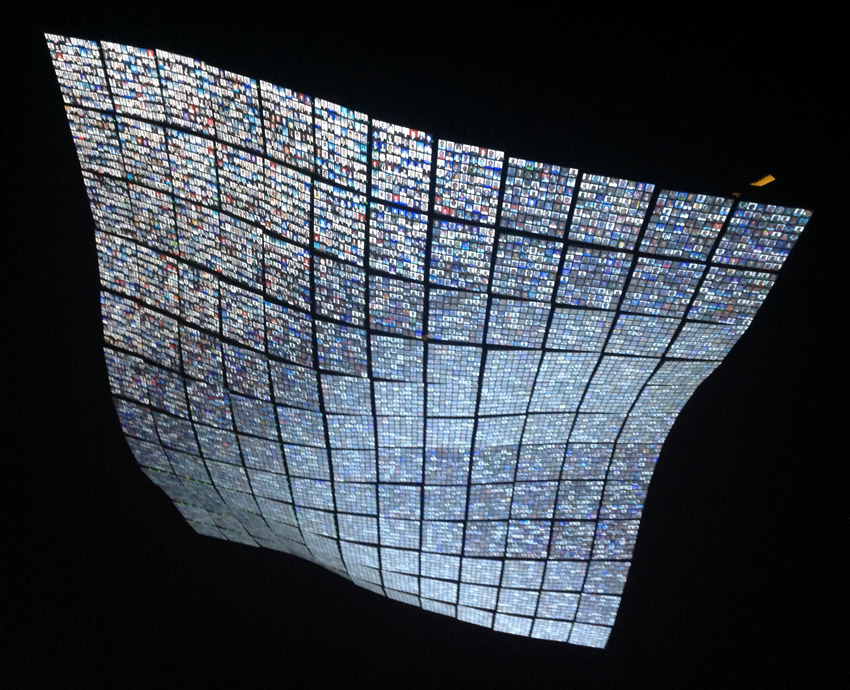

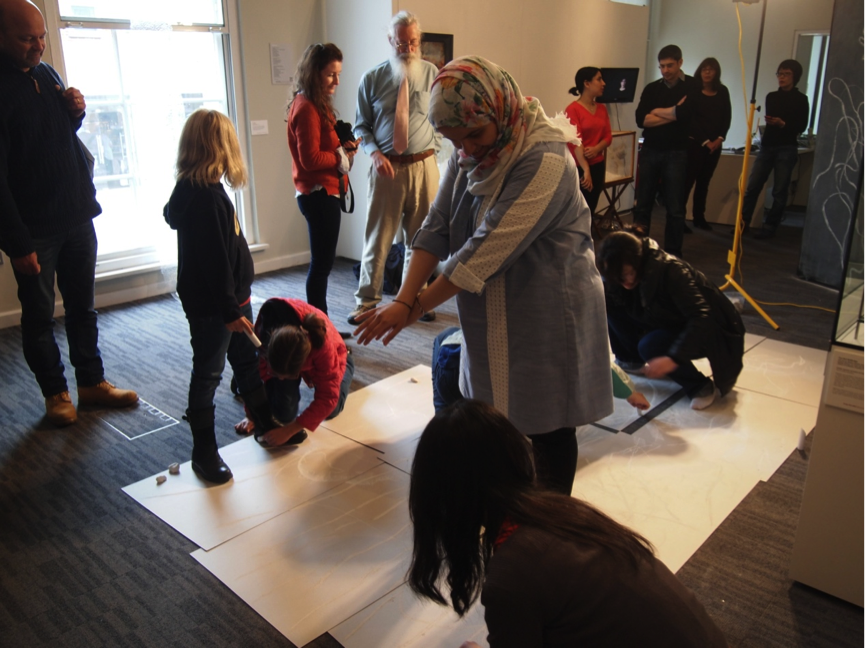

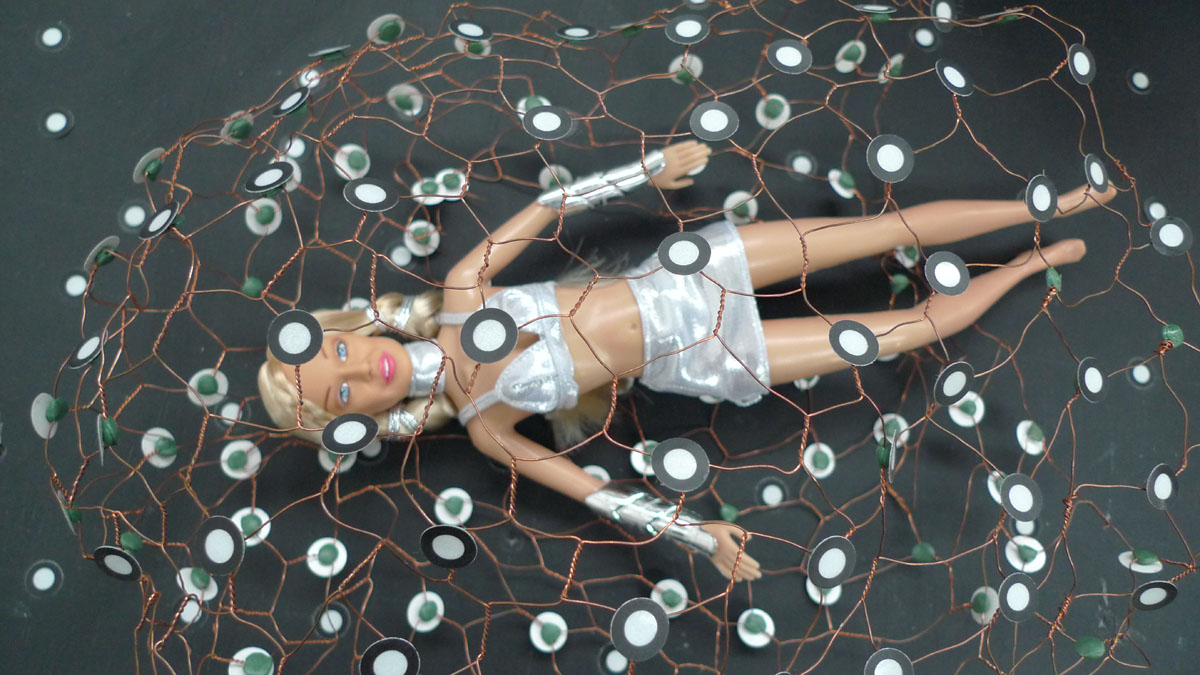

As can be seen with the images included in this post, the seminar worked through a series of different techniques. It began with recording the figures through photographic and digital means for processing in 3D printing softwares. This was a lengthy process, but requiring relatively straightforward and even imprecise means to gain ‘data’ for the softwares to crunch. There is certainly an element of ‘blackbox’ as to how the softwares treat the various inputs to render a three-dimensional figure. However, the process of looking carefully at the models, experimenting with the cameras, lighting and angles prompted lots of discussion and speculation. Working with a sculptor, it was also possibly to think way beyond the narratives that can be played with the two iconic figures and rather consider material processes. It was soon agreed that we need not only to experiment with 3D digital technologies, but also more traditional clay and plastic moulding apparatus. Two very prominent ‘outcomes’ of the seminar were as follows:

– an ability to ‘think’ through process and material. Ian Dawson’s insights into the various processes and possibilities soon eclipsed the initial theoretical consideration of the figures. While their was certainly a confluence of ideas, the need to keep making – to operate through iteration, as a means of critical consideration – meant that the figures (and the processes we applied to them) became the real force within our collaborative thinking. It became necessary to try out different techniques and to have the opportunity to bring the various result together as quickly as possibly, which in turn prompted further ideas. The speed with which you can mock-up objects through 3D printing is of course a boon to the sculptor’s methodology.

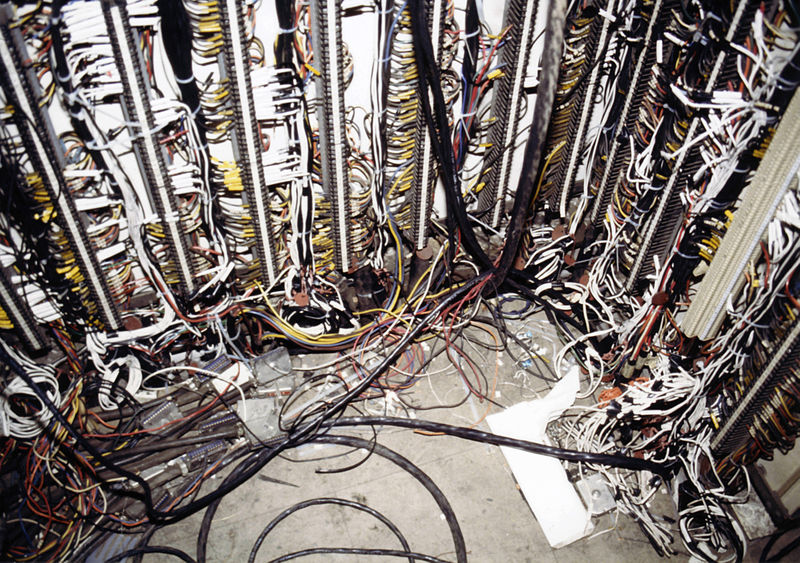

– a material consistency of time and space, or even time-space. From an intuitive way of turning the figures around in your hand to wonder about them, it soon becomes apparent how all of the various techniques for re-making and testing these figures operate through the means of rotation. The video at the top of this post shows the Kylie figure held (on the left) in the rotational moulder, which is a metal set of frames to allow rotation on all axis. On the right, she is shown rendered through 3D software, which again immediately provides the means to rotate in all directions. When a scan is first placed in the software there is no reverse to the image. We are familiar with a sheet of paper having both a front and back. In 3D software the image scan begins with no reverse. As you spin the object it simply disappears. In order to prepare for 3D printing it is necessarily build up the reverse. In a similar way when a mould is placed in the rotating metal frames the ‘object’ has no surface, it is merely outlines by the mould. Liquid plastic is poured in and rotated to gain a even coating, which then effectively gives the object its outside and inside. While all very simple to comprehend the two days of the seminar repeatedly foregrounded this principle and its consistency through many different processes.

Return to Re: Making