Najla Binhalail’s doctoral research examines the practicalities and politics of the museum display of Saudi clothing, with particular consideration of the Unification of the Kingdom Hall in the National Museum in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Her work prompted the readings for a seminar on the function and ‘value’ of the museum . Her account of the seminar she led connects also with her attendance at the recent conference ‘Taste After Bourdieu’.

On Wednesday 14 of May, Dr. Sunil Manghani and eight PhD students from different nationalities studying at the Winchester School of Art took part in a seminar to discuss the cultural identity and value of museums. As this topic is relevant to one area of my PhD thesis, I would like to summarise and comment upon our seminar discussion. I began the seminar by giving out two papers, each summarising a previous piece of research concerning the core function of museums, and one paper and pen for the answers to the question I would ask during the discussion.

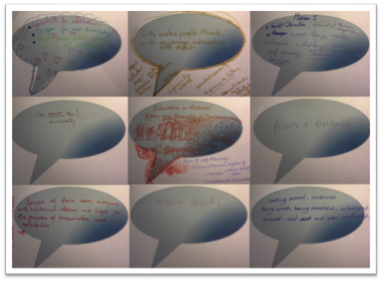

A definition of the word “museum” was then offered as “a building where many valuable and important objects are kept so that people can go and see them”(Dictionary: Rundell and Fox, 2007, p.985). I asked the question, “What is the function of a museum?”, and the group were asked to write their answers on the paper provided and read them out prior to our discussion.

We then watched four YouTube videos (see links below) presenting a varied selection of views and perspectives from both visitors and museum staff in answer to the question I had posed.

We based our discussion on the videos and the summary I had made of two research papers, “The Museum Values Framework: a Framework for Understanding Organisational Culture in Museums, and Museums, exhibits” and “Visitor Satisfaction: a Study of the Cham Museum, Danang, Vietnam.” After our discussion I asked the same question, “What is the function of a museum?”. Again the group gave their answers on the same sheet paper. The purpose of repeating the question was to observe and compare how opinions had changed as a result of our discussion.

In the light of our discussion, I have come to recognize that the word “value” rather than “function” may be more appropriate when describing the aims and purposes of a museum. “Function” tends to imply one overall concept which may or may not be true in any given context, while “value” allows for differences in the economic, political, religious and national needs of each museum, its management, staff, and culture of which it is a part, as well as the wide mix of age, gender, nationality, social and educational background of its audience.

After the seminar I attended the “Taste After Bourdieu” conference at the University of the Arts in London, and as a result I became aware of the relationship between our seminar discussion and a research paper presented by Dr Silke Ackermann, “Have you got a quid?- Museums as development tools in urban culture.”

I understand Dr. Ackermann’s concern, because I am from Saudi Arabia and my culture is similar to that of the United Arab Emirates. Her questions were about the value of museums in an urban culture, and in particular she mentioned three new museums in Abu Dhabi as examples of her concern. My opinion is that there appears to be a different value for the museum in some countries of the West compared with some countries of the Gulf.

Some of the Gulf countries have come more recently to recognize the value of museums. They understand that progress and civilization originate from the roots of the past and are attempting to increase an awareness of the importance of museums. These countries tend to link the existence of museums to the interests of their tourists and non-citizens rather than to the needs of their actual residents. As a result, they plan their museums based on the valued experience of some western countries, with many of their new museums designed by foreign experts from a western culture. I am convinced that such experts will not easily understand the real needs of the citizens of the Gulf region.

Museums keep the valuable objects and display the heritage of the nation. Their presentations need to be distinct, effective, and offer the visitor a pleasing and interactive experience. Museums are not merely storerooms or repositories of the past, they are places of the present and the future, places that tell us the human story throughout the ages in an accurate and true fashion, and thus open up and interpret human civilization for succeeding generations to come. My hope is that the majority of citizens in the Gulf countries will come to appreciate the value of museums for the increase of knowledge and communication, and the strengthening of their political and economic standing in the world.

Resources:

Rundell, M. (2007). In: English Dictionary for Advanced Learners, 2nd ed. Oxford: Macmillan, pp. 985.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FL97lJ2rSdI

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cjx1F-N3YbQ