After doing some research into interfacing electronic signals with the body, I stumbled upon bionic eyes. One device was the ARGUS II, implanted into five patients in England as part of a clinical trial. This article included praise from current ARGUS users Including a man who can now see his grandchildren running around. The articles surrounding the device was overwhelmingly positive until they got more recent then the narrative around ARGUS changed.

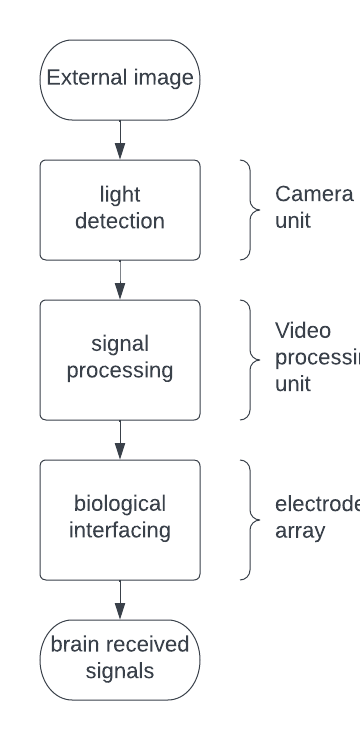

The device is comprised of three modules. An electrode array, video processing unit and a camera. The brain interprets the signals as flashes and the vision created is more akin to an entirely new sense. In this video Ray describes the vision produced as arcs.

The arcs represent the most important parts of the picture. This should be moving objects and edges; the device must accurately pick out the pixels which will convey the most relevant information to the patient. The Video processing unit (VPU) is what does this. It utilizes edge detection algorithms like the matrix mechanics of convolution which I am familiar with from both computer science and quantum mechanics.

The electrical components in the device have several purposes: data and power transfer and biological interfacing. The former is achieved by using magnetic induction. For data transfer the VPU unit encodes signals into radio waves. Which are then converted to tiny alternating currents by a receiver in the implanted region. The data can then be extracted from these currents. Power is transferred by the same physical principle tweaked for this purpose. The final challenge is at the biological interface. The ARGUS II uses micro-electrodes. These define the vision achievable by the device. Advancements in nano-tubes could really improve the quality of the vision created due to physical constraints of wider electrodes.

Despite the quality-of-life improvements seen from most recipients and the prospect of new iterations of devices the device manufacturer Second Sight collapsed and merged with Nano Precision Medical ceasing to develop its ARGUS implant line switching to other projects. The devices had never become profitable. All engineers were laid off and, unlike previously promised, support for the ARGUS models was stopped. Second Sight also failed to inform patients of the collapse. Now users are left to hope their device continues working as normal since replacement parts need to be sourced from the community and many relied upon devices have been rendered not functional by previously routinely fixed hardware issues.

In the EU manufacturers must provide spare parts for a washing machine for 10 years after the appliance has been discontinued. This law was introduced to help limit the environmental impact of E waste and protect consumers. The standard used for washing machines should be the absolute minimum used for implanted medical devices. I believe strongly in the right to repair and choose to repair my own technology, therefore qualified engineers should have access to the parts for device repair long after they have stopped being implanted.

This is a prime example of our increasing vulnerability in the face of high-tech, smart and connected devices which are proliferating in the healthcare and biomedical sectors.

Elizabeth M Renieris, professor of technology ethics at the University of Notre Dame told the BBC https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-60416058

Many have been left with defunct devices still implanted in their body. I believe the stress and anxiety caused for these people is unforgivable and the law needs to catch up, money and company reputation must stop being placed above patients and transparency.

This is an initially reflective and well researched blog showing how you have chosen to explore the emerging field of…

This is a good attempt at a blog, where you reflect on your recent learning at a lecture/workshop to describe…

This is a fair to good blog, reflecting on your recent learning in some of your modules. You provide a…

This is an engagingly written and reflective blog focussed in general on ethics in medicine. You might improve by citing…

This is a good and well written an presented blog on an original subject - biofilms on implants. You explain…