Amidst an ethical debate regarding organ donation in an ethics and law workshop, the complexity of the discussion inspired me to delve further into the moral and legal implications of organ donation. While it is true that organ donation is a lifesaving procedure, it is interesting that when it comes to infants with life-threatening illnesses, it’s not so easy.

Case study

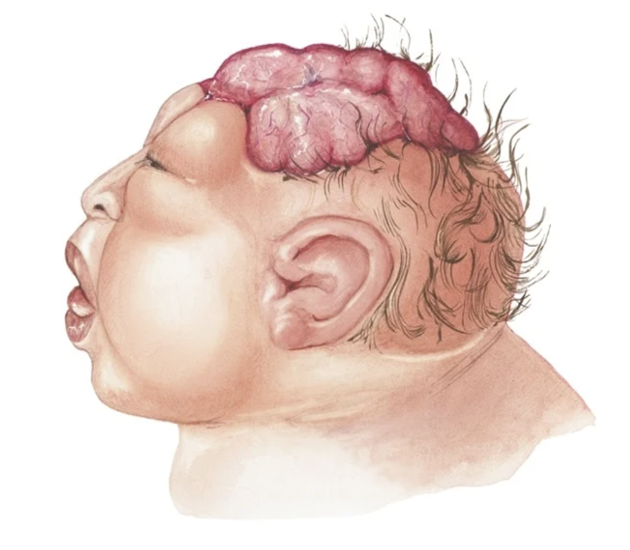

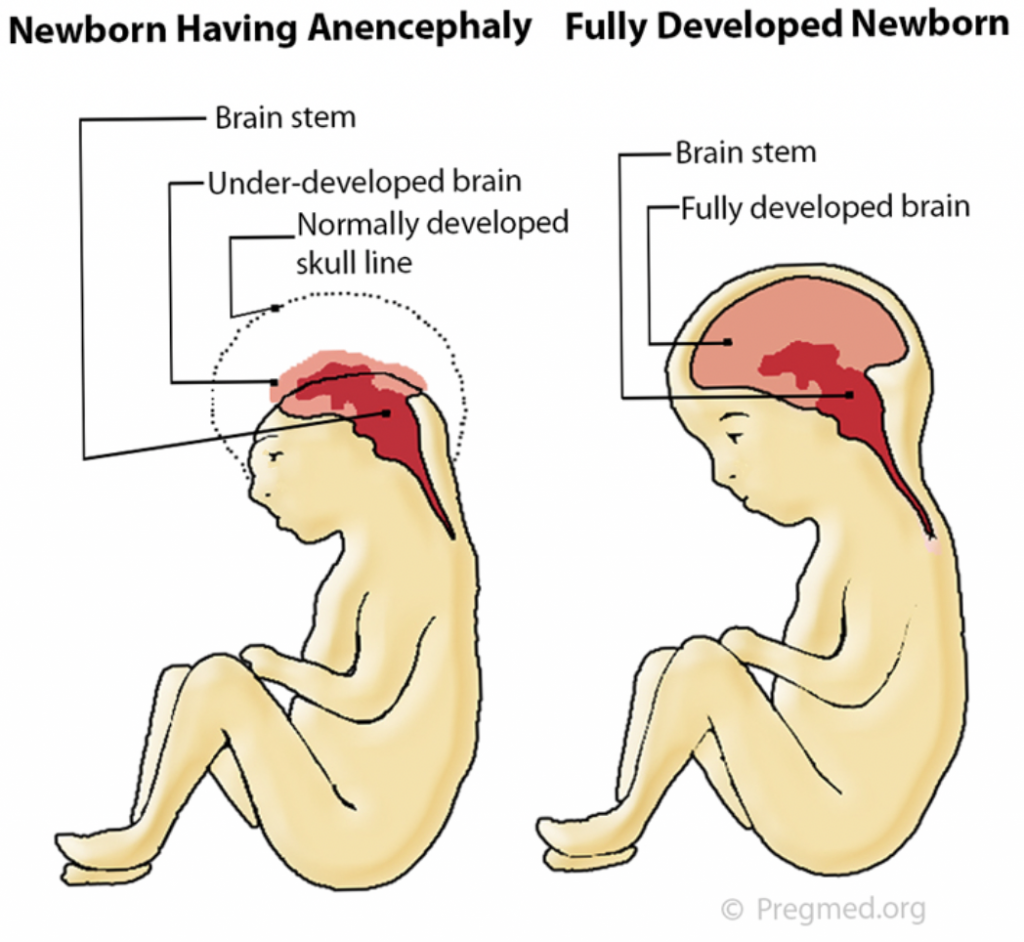

For example, Mrs Z, a young, overdue, pregnant woman underwent an ultrasound examination and was told that her baby was anencephalic – A condition where no brain is present except for portions of the brain stem and there is a high likelihood the baby will be born underdeveloped and stillborn. Heart and kidney transplants could be possible.

In light of this, the mother decided to volunteer her baby as an organ donor. Despite her wishes, the moral debate began as physicians became uncertain on what steps to take. If they accepted the mother’s wish to donate organs, is it their duty to try and resuscitate the baby if it was still born? Should they accept her wishes at all? When should or could the baby’s death be pronounced?

Moral Panic

Mrs Z’s case is a controversial debate, predominantly due to the moral and legal obstacles to taking organs from a pre-diagnosed anencephalic new-born.

To start, following the mother’s requests would be a way to alleviate the growing shortage of vital organs for organ recipients in need. Organ size restrictions mean that strategies to increase donation rates may not be of much use. However, there have been cases where ‘miracle babies’ have lived long after expected. How do we determine who takes priority?

In addition, under current law, organs can be taken from patients who are ‘brain-stem dead’. Despite brain absence, an anencephalic infant does not meet this criterion as they retain a functional brain stem that can maintain vital functions. So, by law, the mother’s desire to donate may not be permitted. The baby should be treated as they would ordinarily be treated, regardless of determined death. Would we normally resuscitate a still-born infant? Prolong suffering? Yet, if these organs have the ability to save the lives of dying infants, I believe that the organs should be donated, provided the baby does not suffer.

Finally, in actuality, there is no reason why the parents shouldn’t be able to donate the organs of their baby to suitable recipients, provided it follows the death of their child. But… the glorification following the words ‘organ donation’ makes me wonder if the parents were informed on alternative approaches for recipients, such as stem cells or Norwood staged surgery. Were they aware that the absence of a major part of the brain doesn’t imply instant brain death? Is this pure utilitarianism? I believe it should be standard that families who request organ donation from their anencephalic baby should be given concise information and educational material provided on the practice and its implications.

Final thoughts

In my opinion, if there is a way to donate Mrs Z’s baby’s organs without drastically intervening standard treatment, organ donation should proceed. However, the answer differs if a significant alteration occurs. Going above and beyond to prolong gestation on a distressed infant in order to ‘mature’ organs for donation requires moral reservation.

Nevertheless, recent research has diminished the idea of anencephalic new borns as organ donors, with the exception of theoretical debate and case studies. The American Academy of Paediatrics (1992) concluded that organ donation from anencephalic infants should not be undertaken due to the serious difficulties surrounding the establishment of brain death and limited success rates.

This is an initially reflective and well researched blog showing how you have chosen to explore the emerging field of…

This is a good attempt at a blog, where you reflect on your recent learning at a lecture/workshop to describe…

This is a fair to good blog, reflecting on your recent learning in some of your modules. You provide a…

This is an engagingly written and reflective blog focussed in general on ethics in medicine. You might improve by citing…

This is a good and well written an presented blog on an original subject - biofilms on implants. You explain…