As someone who is very interested in biological fiction, I am currently reading ‘The Body’ by Bill Bryson. I came to the chapter, ‘In the Dissecting Room: The Skeleton,’ and was intrigued to hear that medical cadavers have been the topic of various controversies throughout history. Soon after reading this, I also attended the ethics and law lecture, which led me to delve deeper into the issues and history of acquiring medical cadavers for teaching.

Where did medical cadavers previously come from?

Public opinion of dissection around the 18th and 19th century, even for the benefit of science, was seen as sickening and disrespectful. Fitting with the questionable ethos of the time, only hung criminals were seen to warrant this brutal fate. I was appalled to discover that this was justified by judges who believed murderers deserved further prosecution after their execution, so offered their bodies up for dissection without choice.

Why did this need to change?

Still, there never seemed to be enough cadavers to distribute between medical schools. Bryson mentions in his book that in 1831, London had 900 medical students with only 11 cadavers. This ultimately led doctors to turn to grave robbing. These hellish actions were not a punishable offence at the time, which only encouraged them to continue. I was shocked to hear this, but it made me realise that legal enforcement was the only way forward to put a stop to the clearly desperate thievery. My research led me to find that the Anatomy Act of 1832 was enforced because grave robbing had gotten too out of hand. This allowed medical institutions to also take ownership of the bodies of unclaimed poor persons.

While this seemed to fix the shortage and improve standards of anatomy textbooks, I found it shocking to believe that the financial status of a person upon their death should determine the fate of their body. Can the sacrifice of convicts and the poor be justified for the greater good of science? Rather than discarding abandoned bodies, should they be put to better use? I can see balance in this argument, but it is hard to believe doctors had free license to dissect unclaimed bodies. This opinion was shared by many.

“They tell us it was necessary for science. Science? Why, who is science for? Not for poor people. Then if it is necessary for science, let them have the bodies of the rich, for whose benefit science is cultivated.” – William Cobbett (1763-1835, advocate for English poor and working-class)

Where do medical cadavers come from now?

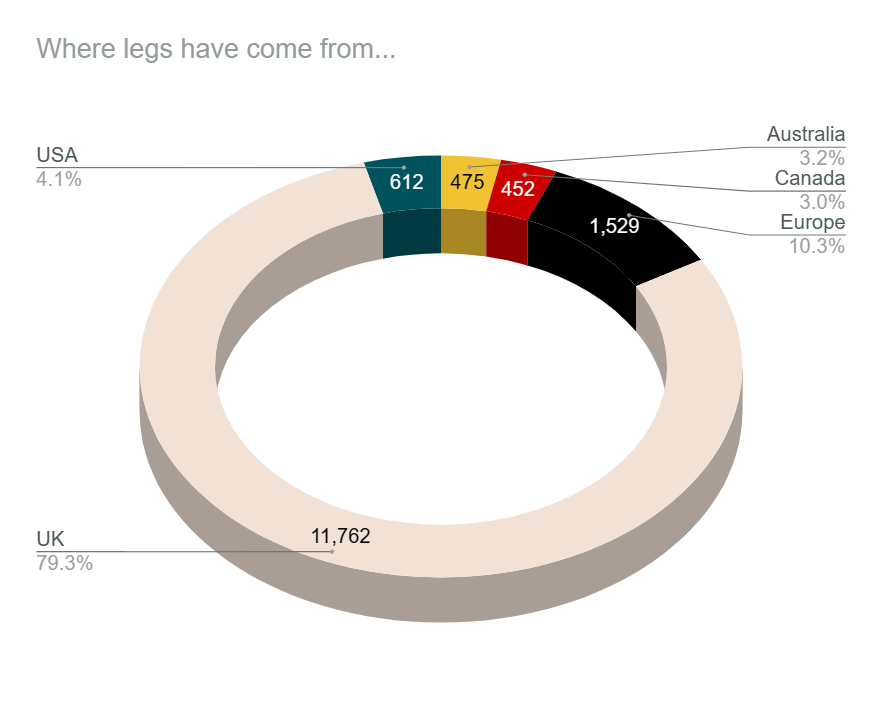

Under the Human Tissue Act 2004, written and witnessed consent for anatomical examination is required prior to death, it cannot be made by anyone else after a person has died. In the UK, It is illegal to buy and sell human remains, therefore modern medical schools rely entirely on donations of those willing to give their bodies for science. I was even pleasantly surprised to hear that some schools are positively overwhelmed by donations that they must turn away excess offerings.

A current perspective:

I was intrigued to see what current medical students thought about cadavers and the regulations implemented by Southampton University. I consequently conducted a short interview with a student which I found very insightful, as shown below.

A real-life nightmare:

Unfortunately, I was devastated to find that some countries still use unclaimed bodies for teaching. I found a truly awful news article where a student from the University of Calabar in Nigeria was traumatized by an anatomy class that used the dead body of his friend. I discovered that 90% of Nigerian medical cadavers are criminals killed in shootings. Whilst this story truly horrified me, it shows that there is still a global shortage of legitimate cadavers .

I believe there should be tighter universal regulations that limit the distribution of unclaimed bodies for science, but similarly increase international positive awareness to encourage more people to donate their bodies. This may be the only solution to permanently fix shortages without overstepping ethical practice.

This is an initially reflective and well researched blog showing how you have chosen to explore the emerging field of…

This is a good attempt at a blog, where you reflect on your recent learning at a lecture/workshop to describe…

This is a fair to good blog, reflecting on your recent learning in some of your modules. You provide a…

This is an engagingly written and reflective blog focussed in general on ethics in medicine. You might improve by citing…

This is a good and well written an presented blog on an original subject - biofilms on implants. You explain…