“I think, I am.“

These famous words were written by Rene Descartes in his book Meditations in 1641. It deals with the philosophical theory of knowledge or as known as epistemology. The reason I am writing the blog on this topic is derived from the lecture in week 6. During this, the lecturer mentioned sensation and haptics in prostheses that bring another level of sensory input for the disabled. This topic echoed my previous reading on Descartes. In the book Meditations, Descartes advocates the separation between the mind and the senses. Where senses are gathered from experiences, the mind holds some fundamental knowledge. For example, Descartes gave the example of a dream argument, that the senses in a dream can deceive a person, such as the smell and the touch. But fundamental knowledge such as colour, and the three-dimensional environment are the same as reality. While the senses can be wrong, and the mind is fundamental, as a result, the separation enables one to seek the fundamental truths, as Descartes argues. However, Descartes is also a mathematician. And the fundamental truths in Descartes’ view are factors that form our reality, such as physics, and 1+1=2. But what about the senses? Our own way of perceiving reality?

For matters such as a person predicting when the bus will arrive, or the action of a person if one says certain phrases to them, the prediction can usually be correct, only if they have gathered enough knowledge through senses in the past. This type of knowledge can be fitted into Bourdieu’s theory of practice, where some of the predictions are formed by habitus, in another word, a societal structure that determines how we think and act.

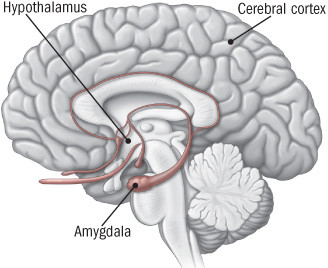

But what about instincts? A newborn baby will instinctively seek nutrients, we breathe with our lungs without learning it from schools, and we retract our hand muscles when we touch something hot. These actions are not determined by habitus but by stimuli. Lorenz’s research on animal instincts (ethology) with ducklings points toward that the hatchlings are born with learning programmes, which only need to be activated by stimuli. The ducklings were born to be attracted to certain stimuli that resemble the features of a mother hen, which is similar to human infants learning to recognize faces. Humans have fight-or-flight instincts that trigger certain parts of the brain when faced with dangerous situations. We also eat, drink, and rest based on body chemistry.

Reflection

Based on scientific evidence, the habitus of society, as mentioned, guides one’s behaviour. Yet the habitus itself is created through a social pattern. And it could be argued that social patterns are based on biological responses. One could, as I did as well, fall into the trap of a nihilistic view on this matter, that society is nothing but a complex exchange of chemistry responses that guides what we perceive as the “reality”. However, “I think, I am”, I refuse to be defined by a set of chemistry responses, but through my senses, and what I experienced throughout time.

From this mode of thinking, strong moral support for medical advancement can be derived. Imagine the reality perceived by someone who suffers from nerve damage that affects any of the five senses since birth. The reality perceived by them will be totally different. Without medical advancement for prostheses and other surgical treatments, living in a reality without realising the reality is false due to uncontrollable factors is a really cruel thing to think about. Like Descartes’ theoretical example of a deceptive god that intentionally created reality to always be false. It is a great evil if this was to be true. As such, some medical advancements can really be something to be awe of.