Introduction

Sensation is a crucial aspect of everyday life; it allows us to feel texture, pressure, and temperature of objects that we interact with.

Now imagine trying to pickup a delicate object without being able to feel it in your hand, how hard do you need to squeeze your fingers to hold it without the object falling out of your hand? Or are you gripping too hard that you might break it? This lack of sensory feedback is a major concern of prosthesis users and here we will explore the methods of sensory feedback.

Here is Dr. Ian Williams discussing developing a prosthesis with sensory feedback:

The role and history of sensory feedback for prosthesis users

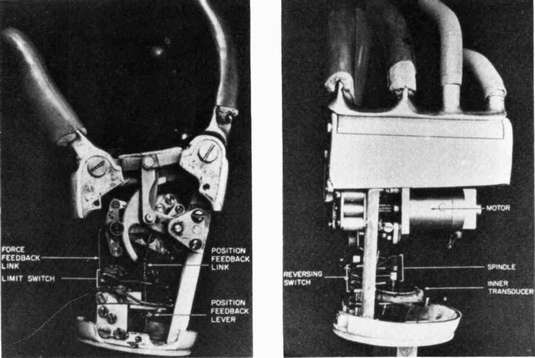

The idea of restoring sensory feedback in prosthesis has been around since 1917 when Rosset patented a mechanism (Patent No. DE301108) that relays finger pressure via pneumatic or mechanical means. Many others followed, like the Vaduz prosthetic hand in the 1940s (Patent No. 2567066) which provided voluntary-closing hand and a “bladder” which was connected to the residual limb in the socket to provide force feedback. However, amputees still struggle with using these prosthetics as the user can’t tell what their prosthetic is doing without having to actively look or pay attention to what their prosthetic is doing. This is due to the lack of proprioception. (1)

Different types of sensory feedback

There are several methods that attempt to incorporate sensory feedback for upper limb prosthetics that try to provide users with sensory information. (1)

- Electrostatic feedback

- Electrostatic feedback involves the use of electrical signals to stimulate the skin and provide sensory feedback.

- Mechanotactile feedback

- Involves the use of mechanical pressure or vibrations to stimulate the skin and provide sensory feedback about the position and movement of the limb.

- Sensory substitution

- Involves providing sensory information through a different modality than the missing limb such as using visual or auditory feedback to replace the sense of touch in the hand.

- Invasive feedback

- Involves the use of implanted sensors to provide feedback about the prosthetic limb.

Additionally something else that needs to be taken into account is the time it takes for the feedback to reach the nervous system and be processed. Therefore, different feedback methods need to consider time delay when designing their systems. (2)

My insights and reflection

Sensory feedback plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between human limbs and artificial limbs. There are undeniable benefits in introducing sensory feedback in prosthesis such as enhanced functionality and improved quality of life including, providing a sense of proprioception to amputees. However, there are still several challenges faced in restoring sensation.

These include:

- Expanding the range of sensations

- Allowing the user to feel textures, temperature and also pain.

- Personalisation and adaptability

- Everyone is different and the ability to accommodate for a fit, growth and usage of the prosthesis is a huge challenge in meeting individual needs.

- Affordability and accessibility

- At this moment advanced prosthetics are prohibitively expensive and only a small handful of people around the world have the opportunity to have even basic sensory feedback.

An ethical and tricky question to consider is: Should we have artificial pain? This is a whole topic that could also lead to another post, but briefly, it has benefits for being a warning mechanism for potential harm, providing a realistic experience and better decision making. However ethical concerns arise if it is morally justifiable to subject users to distress, the level of pain intensity and how are you able to stimulate pain.

References

1. Antfolk C, D’alonzo M, Rosén B, Lundborg G, Sebelius F, Cipriani C. Sensory feedback in upper limb prosthetics. https://doi.org/101586/erd1268 [Internet]. 2014 Jan [cited 2023 Mar 24];10(1):45–54. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1586/erd.12.68

2. Sensinger JW, Dosen S. A Review of Sensory Feedback in Upper-Limb Prostheses From the Perspective of Human Motor Control. Front Neurosci. 2020 Jun 23;14:345.