Having grown up with mild to moderate bilateral sensorineural and conductive hearing loss, I have always worn hearing aids. This sparked an interest in audiology and hearing technology which has inspired me to research the intricacies of cochlear implants, particularly as we will be learning more about this later in the module.

So, what is a cochlear implant….

A cochlear implant (CI) is a device that allows people with severe to profound hearing loss to experience sound by transmitting electrical signals via the auditory nerve. The user interprets these sensations as sound. In contrast, my hearing aids only amplify the frequencies I cannot hear.

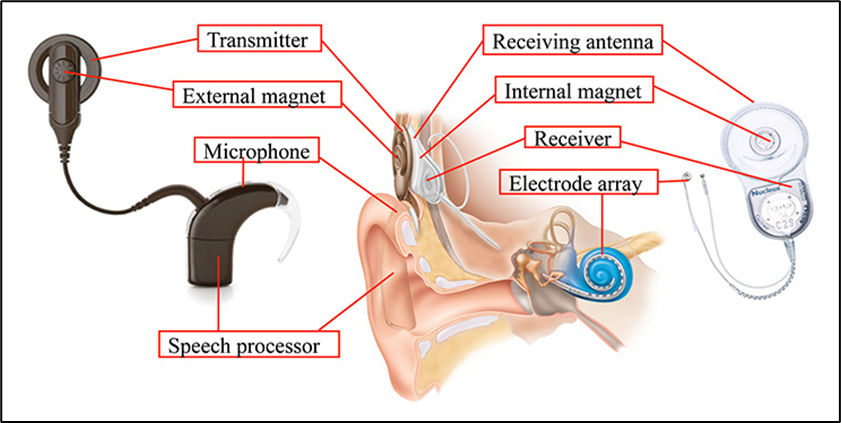

A CI is composed of external and internal components, as illustrated in the diagrams below. External components include a microphone, speech processor and transmitter, whilst the surgically fitted internal components are a receiver and an electrode array.

The mechanics behind CIs is relatively straightforward. Externally, the microphone transmits sound to the speech processor which converts sound into a digital signal. This signal is sent, using a magnet, via a transmitter to a receiver located under the skin. The receiver circulates signals to the electrode array in the inner ear that stimulates nerve fibres triggering the auditory nerve in the cochlea. As a result, the brain recognises incoming sounds. Remarkable!

A helpful video on cochlear implants is below:

Whilst researching CIs, what astounded me the most was the rehabilitation process. It had never occurred to me just how difficult it would be to adjust to sounds if the user has no hearing memory and therefore struggled when sound was different to what they perceived it might be.

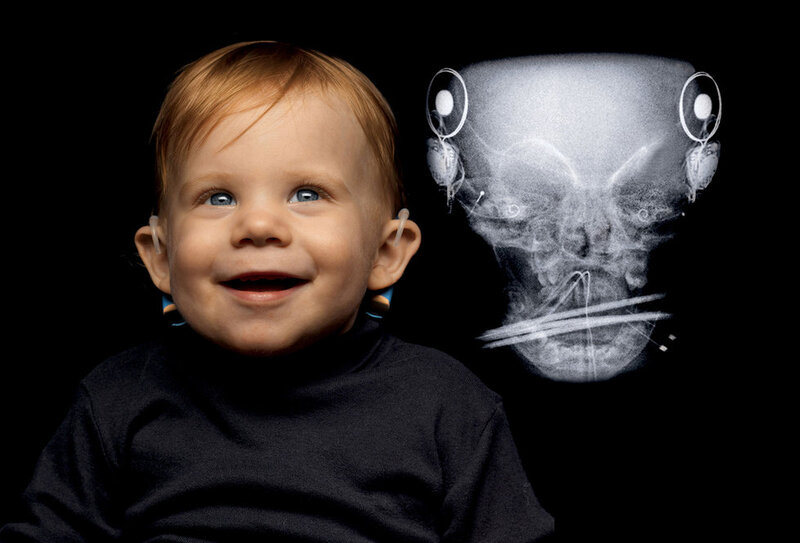

To understand this, I contacted a friend who is profoundly deaf in both ears since she was 21 months old. She received her left CI at 2½ years and right CI aged 8. Her CI has hugely benefitted her communication with others and listening to music, both of which she previously found challenging.

The hardest part of her rehabilitation process was undergoing years of speech therapy to adjust to the new sounds. To adapt to the second CI, she read her schoolbook aloud only wearing the second CI. After several months she could hear properly through it. However, she found it difficult to adjust to the new directionality of sound introduced by the right CI. Unfortunately, this meant she never fully acclimatised to hearing through both CIs and for that reason she only wears her first CI.

This intrigued me further to investigate what facilitates the rehabilitation process.

According to the British Cochlear Implant Group, rehabilitation is a structured programme, known as auditory training, involving exercises and a Speech and Language Specialist. This helps users to interpret and differentiate sounds, as well as translate words into speech.

Whilst my friend was unable to recall her auditory training, another blog highlighted strategies for successful rehabilitation:

- Commit to daily exercises incorporating them into everyday activities (e.g., listening and repeating categories of words in quiet and loud environments)

- Listen to audiobooks and podcasts altering volume, speed and accents

- Use interactive apps (e.g., Cochlear CoPilot)

My final closing thoughts …

Writing this blog has opened my eyes to the incredible resilience and dedication required by a CI user when adapting to new sounds. Furthermore, a CI is an amazing device that significantly improves the user’s quality of life and therefore socioeconomic opportunities. One paper illustrated a 21% increase in self-reported benefit as well as an average word perception increase up to 53.9% (Boisvert, et al., 2020).

Further interesting links include: