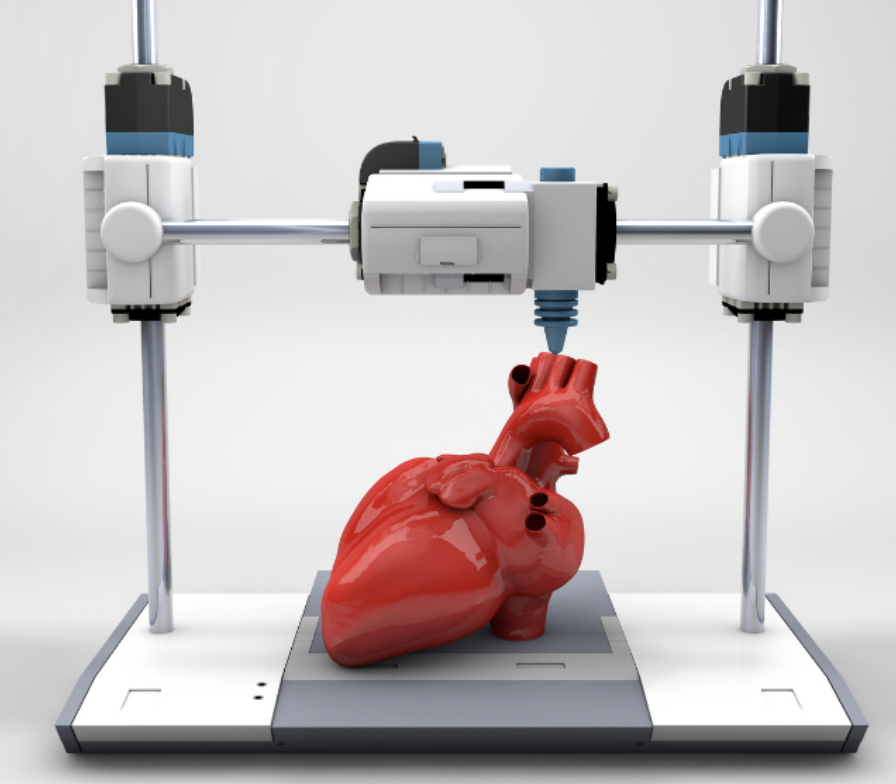

Although the title may seem farfetched, we aren’t as far away from this as it may seem. 3D printing is a technology which is rapidly growing, and is perhaps the answer to many problems within science and medicine.

I became fascinated with the possibilities of tissue engineering after a lecture a few weeks ago, which led me to further research some of the current advances and future possibilities in the field.

It has been 70 years since the first organ transplant, which was a kidney. Since then organ transplant has become a common procedure and has saved many lives. However, there is still some problems associated with it. According to a study by Conor Steward, as of the end of March 2022, there was 4,744 patients on the transplant list in the UK. This long list is costing lives everyday, 3D bioprinting can speed up this process and save lives every day.

So how does this work?

There are three key steps in the process:

- Pre-bioprinting – A Digital file is created to input into the printer, telling it what to make. This is often made using MRI and CT scans of the organ you want to print. The cells are then mixed with a bioink, and imaged to ensure they are suitable for the procedure.

- Bio-printing – the cell and bioink mixture is placed into the printer, along with the digital file. It is then mixed with a hydrogel as it prints, which is essential in created the structure, as it acts as a scaffold.

- Post-printing – to further enhance the structure, the cells are cross linked. This may be via UV light or the application of an ionic solution, depending on the structure.

But where are these cells coming from?

Something that shocked me, whilst learning about tissue engineering, was the range of different sources of cells, and the ethical problems associated with some of them.

The cells may come from a donor, which is known as allogenic cells. There is the possibility here to violate two of the most important laws in biomedical research – confidentiality and consent. In addition to this, one of the problems that strikes me is that it does not reduce the possibility for rejection.

Perhaps one of the most controversial sources is Embryonic stem cells. This involves using embryos to derive stem cells for. However it brings up one of the most pressing questions in biomedical ethics – what is the moral status of an embryo.

However, these ethical issues can be overcome by using stem cells from the patient, that is undergoing the procedure. Cells from your own body are referred to as autogenic cells.

When this comes to mind, you may think of taking stem cells from the patients bone marrow, which is widely used. However I was fascinated to hear how umbilical cord blood can be stored, in the case that a person may need stem cells for any reason in the future. Imagine the possibilities of having your own stem cells, ready for use, in case you ever need them!!

3D bioprinting beyond transplantation

Before researching the use of 3D printing, I thought the only use for these organs was transplantation, however as a scientist, I was fascinated with how they are used for research.

The possibilities of the technology are endless, with studies creating beating hearts, pancreases to cure diabetes, and even a new ear to restore hearing! But in addition to this, we can print tumours or disease models to understand the behaviour of cells!

One study that caught my attention was using 3D printing to create mini tumours, in order to create a more personalised and potent treatment for cancer patients. Scientists at the Seoul National University College of Medicine, formulated a range of bioinks from patients with glioblastomas, which the most common type of brain tumour. A range of chemotherapy and drugs where then tested on these tumours, to allow the scientists to understand how best to treat these tumours. The applications of 3D printing in terms of drug development, is something I am excited to see develop in the future.

Where can it go wrong?

Despite avoiding some the ethical dilemmas associated with xenotransplantation or clinical organ donation, 3D printing brings its own range of moral questions associated with it. In order for the techniques to be readily available, there needs to be tight regulations put in place first.

One problem that strikes me, and many others, is the accessibility of these organs and even personalised medicine. With a technique so new, it will take some time to become widely available, so who gets it first? A problem that has arose a lot within medical ethics, is the use of these products for performance enhancement. This may be particularly prevalent within sports, however it applies to everyone. If you had the money to afford these technologies, you would be able to live a longer life or enhance your quality of life. This sounds great, right? But on the other hand, there is the patient stuck in hospital waiting for an organ transplant, with a life ahead of them with a strict drug regime to avoid the risk of rejection. Is this fair?

In order for the technique to work, particularly to begin with, laws would need to be put in place that the technique should only be used for medical practice, in terms of organ transplant. However personalised treatment plans may be a different issue, as it would be highly beneficial in terms of medical practise, however still separates society.

Personally, talking a utilitarian view point, I believe that the benefits of the techniques are huge, and therefore outweigh any possible socioethical issues that may arise. However as stated above, I don’t think it should be used primarily for performance enhancement, until the technique is widely accessible to everyone, as it creates a larger divide in society than there already is.