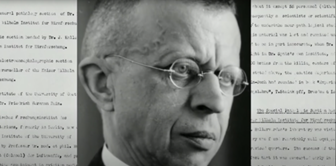

In the first lecture regarding the ethics and law of using humans in research, we discussed the case of Julius Hallervorden, a prestigious German physician and neuroscientist who operated during World War II. Hallervorden’s research sparked great debate, as he received up to 2000 brain samples from the Nazi euthanasia programme, where certain German physicians were authorised to select patients under the age of 18, “deemed incurably sick, after most critical medical examination”, and then administer to them a “mercy death” [1]. While he did not directly participate in the programme, using these materials Hallervorden published several articles during the post-war years furthering the understanding of multiple neurological disorders, even having a condition named after him and his colleague, Hugo Spatz, Hallervorden-Spatz disease.

Furthermore, Hallervorden denied any responsibility for the deaths of his subjects, stating “If you are going to kill all those people, at least take the brains out so that the material can be utilized”, as he continued, “I accepted the brains, of course. Where they came from and how they came to me was really none of my business”. Hearing Hallervorden’s opinion added to the controversy, trying distance himself from the atrocities, while others would argue he is complicit with the forced euthanasia.

After reading related articles and scouring YouTube, I discovered bioethicist Jürgen Peiffer, who reported multiple papers published by Hallervorden that likely used data collected from brain sections of “euthanasia” victims [2], also noting the terminology used, as he referred to patients brains as ‘material’, which Peiffer believed showed a lack of compassion. After Hallervorden’s death in 1965, the science community began to object his publishments, culminating in the renaming of Hallervorden-Spatz disease nearly 40 years later in 2003 [3].

During the lecture, we discussed in small groups our own opinions on this case, which allowed me to reflect on all views regarding Hallervorden’s research. I realised just how controversial this topic was, as it showed the unanimously horrific practices of the Nazi party still influenced modern research.

My personal opinion

Coming from a scientific background, I can understand the desire for knowledge that drives researchers ambitions to discover the unknown. I believe this is a principle found in all individuals but is more prominently hard wired into scientists. That being said, I also believe that everybody, scientist or not, should have a moral compass strong enough to realise what is ethically and morally acceptable.

I do not believe Hallervorden was an evil individual, rather his ambitions and desires were filled without limit, which ultimately hindered his moral judgement. In other words, he realised he had an opportunity to conduct revolutionary medical research and took it without considering the ethical and moral implications of his work.

Whether or not we should use his research is an infinitely complex debate. On the one hand, the research has contributed to our understanding of complex disorders, potentially saving countless lives. Additionally, to not use the research would be a waste, a similar justification to Hallervorden’s. Contrastingly, I believe it is not acceptable to credit someone who was complicit with such atrocities, and to do so would be inconsiderate and insensitive to the patients families, as well as tarnishing the reputation of scientific research as a whole.

To conclude, I believe Hallervorden should be striped of his accolades and no longer be credited for his research, however, I think the research should be used as it could save lives and provides a foundation for more research in this area.

References

- Proctor, R.N. and Proctor, R., 1988. Racial hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis. Harvard University Press. Available here.

- Peiffer, J., 1999. Assessing neuropathological research carried out on victims of the ‘Euthanasia’ programme: With two lists of publications from Institutes in Berlin, Munich and Hamburg. Medizinhistorisches Journal, (H. 3/4), pp.339-355. Available here.

- Hayflick, S.J., Westaway, S.K., Levinson, B., Zhou, B., Johnson, M.A., Ching, K.H. and Gitschier, J., 2003. Genetic, clinical, and radiographic delineation of Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(1), pp.33-40. Available here.

This is a good, well written and reflective blog drawing on your experience in one of the sessions on ethics. You focus on an individual story and use it as a tool to explore wider ethical debates.

You might improve this by providing a bit more critical analysis of your own personal opinions. What are the arguments against some of the conclusions you have drawn, and can you provide your own, underpinned by evidence- for example, can you weigh up benefit and harm?