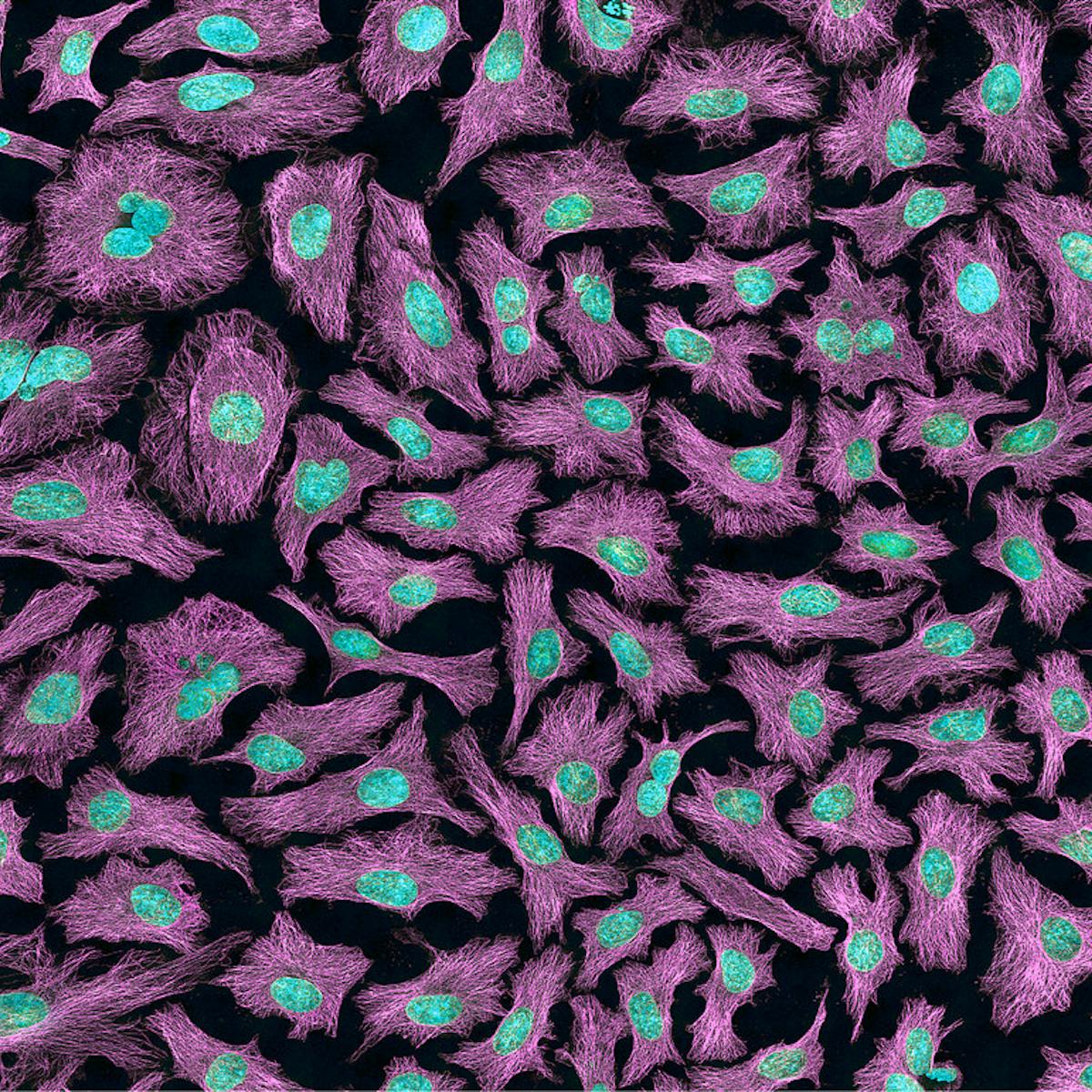

If you’ve taken any lecture within the realm of cell biology – be it about cell division, transport, signalling, and so on – you’ve most likely encountered an experiment involving the use of HeLa cells. I certainly did, and after repeatedly seeing images of those strange, purple cells on my lecture slides, it made me wonder “What exactly is so special about HeLa cells that they are used in virtually every experiment to do with human cells?” This blog post is about these cells: what exactly makes them so remarkable, their polarising legacy, and the important bioethical discussions they raise about medical consent and racism.

What are HeLa Cells?

HeLa cells are an immortal cell line derived from the cervical cancer cells of Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old black woman and mother of five. They are the oldest and most used human cell line in scientific research and have contributed to countless scientific studies since their discovery in 1951.

Lacks was a patient at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland in 1951, being treated for a very aggressive form of cervical cancer. Several months before her death, a sample of her tumour was given to George Gey, the head of tissue culture research at Hopkins at the time. Gey had been searching for an immortal human cell line to study cancer with for two decades and he had finally struck gold: Lacks’ cells multiplied faster than any cells he had ever seen, reproducing an entire generation every 24 hours. Unfortunately, it was this rapid and unlimited division that caused Lacks’ cancer to metastasise to virtually every organ in her body within months. She passed away on October 4, 1951.

The dicey bioethics of HeLa cells

It is quite difficult to put into words just how impactful Henrietta’s cells have been on medical research. They were used to develop the polio vaccine, study leukaemia, AIDS, and cancer, and more recently, help develop COVID-19 vaccines. Since their isolation, HeLa cells have been used in more than 70,000 scientific studies around the world as of 2022. There is a darker side to this story, however.

After her passing, Henrietta Lacks was buried in an unmarked across from her family’s tobacco farm in Virginia. For the next twenty-odd years, her family had no clue her cells had been shipped worldwide and were being used pioneering medical research. It wasn’t until 1975 that the Lacks family even were made aware about the widespread use of her cells in said research.

Henrietta’s cells were taken without her consent, which was legal at the time. Since then, policy changes have been made, and ethical guidelines for medical research have been put in place like the Declaration of Helsinki, which places emphasis on the informed consent of patients. In the USA, changes are being attempted to be made to the Common Rule, the set of ethical policies for research with human subjects, to make its consent rules more far-reaching.

Racism in science and Henrietta’s legacy

In my opinion, what Lacks’ story really highlights is the racism that has historically plagued science, particularly medical research and services in the United States. Hopkins, where she was treated, was one of the few American hospitals at the time that would admit black people. None of the multiple biotechnology companies whose research benefitted from her cells have financially compensated her family. In the 1840s, James Marion Sims, known as the “father of modern gynaecology”, infamously conducted experimental gynaecological surgery on enslaved black women without anaesthesia. There was also the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, when hundreds of black men in the 1930s were denied treatment for syphilis by researchers so the progression of their symptoms could be studied. I have linked further reading on both cases and more general scientific racism at the end of this blog.

While it is important to reflect on these past injustices, what the Lacks family would like to shift the focus is to is the legacy of Henrietta herself. In 2010, the Henrietta Lacks Foundation was established by Rebecca Skloot, the author of a book about Lacks, which awards grants to her descendants and other family members of people whose bodies were used without consent in research. In 2020, on her centennial year, the Lacks family started the #HELA100 initiative to celebrate her life and legacy.

Henrietta loved to dance and cook. She dressed stylishly and wore red nail polish. And most importantly, in the words of her grandson: “[Her cells] were taken in a bad way but they are doing good for the world.”

:focal(808x298:809x299)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/c3/53c3b6a3-929b-43f1-bf61-2d2cafbbecca/lacks1.jpeg)

My thoughts

I wanted to write about Henrietta Lacks for my blog post because as someone who wishes to work in biomedical research in the future, I will probably end up working with these cells myself and I think it is important to highlight the legacy of these cells: both the unjust way in which they were acquired, and what we and the scientific community at large can learn from these past injustices so we do not repeat them.

As a woman of colour myself, I have rather mixed feelings on HeLa cells. It is chilling thinking about the horrific treatment people of colour, and especially women of colour have faced in historical medical research. However, HeLa cells have done so much good for the world and do so for all ethnicities. As long as we acknowledge the story of Henrietta and continue to compensate her descendants, I think HeLa cells can continued to be used in research.

Much progress has been made on bioethics and informed consent in medical research and treatment since that extraction was made from Henrietta’s tumour all the way back in 1951. However, as biotechnology continues to advance and gene editing and the like becomes more commonplace, the door has opened to once again start having these important discussions on how to ethically apply these new technologies.

References

Johns Hopkins Medicine (2023) The Importance of HeLa Cells, Johns Hopkins Medicine. The Johns Hopkins University, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation. Available at: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henriettalacks/importance-of-hela-cells.html (Accessed: March 8, 2023).

Martinez, I. (2022) What are HeLa cells? A cancer biologist explains, The Conversation. The Conversation Trust. Available at: https://theconversation.com/what-are-hela-cells-a-cancer-biologist-explains-169913 (Accessed: March 8, 2023).

Nature (2020) Henrietta Lacks: Science must right a historical wrong, Nature. Springer Nature. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02494-z (Accessed: March 8, 2023).

Skloot, R. (2000) Henrietta’s Dance, Johns Hopkins Magazine. Johns Hopkins University. Available at: https://pages.jh.edu/jhumag/0400web/01.html (Accessed: March 8, 2023).

More Reading

James Marion Sims’ experiments on enslaved women

The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot is a great non-fiction book about Lacks and HeLa cells, and goes into great detail on the ethical issues of race and class in medical research. There is also a film adaptation of the same name that can be watched on HBO and HBO Max.

This is a very good, reflective blog that clearly indicates your motivation for pursuing this area of independent research. It is engagingly and clearly written and balances some science with some discussion of ethics.

You could improve this blog by taking a more critical, evidence focussed approach to provide support for your evidence or to counter any arguments. This could be based on reputable sources that help develop an argument. Hyperlink sources and weigh up their quality. There is a good balance of media in this piece.