In 2002, a woman called Karen Keegan underwent a genetic test to find a suitable kidney donor within her family. Results were astonishing: Karen was not the mother of her sons.

Karen was later discovered to be a human chimaera with 2 distinct sets of DNA, with that in her blood cells different compared that of the other tissues.

The video below explains in more detail Karen’s story and introduces the phenomenon of chimerism

A chimaera is a single organism or a tissue which contains cells with at least two different sets of DNA. Since all animals develop from a single fertilised egg, every single cell of the body is supposed to have exactly the same DNA.

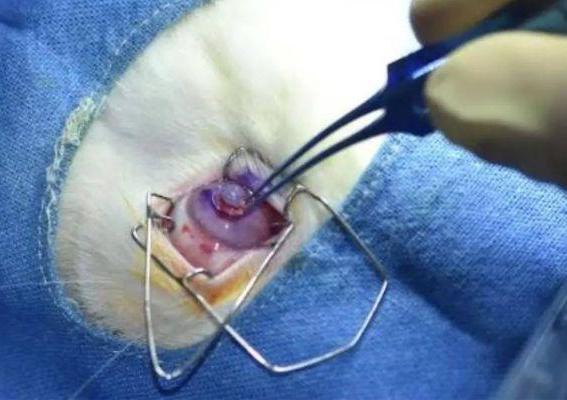

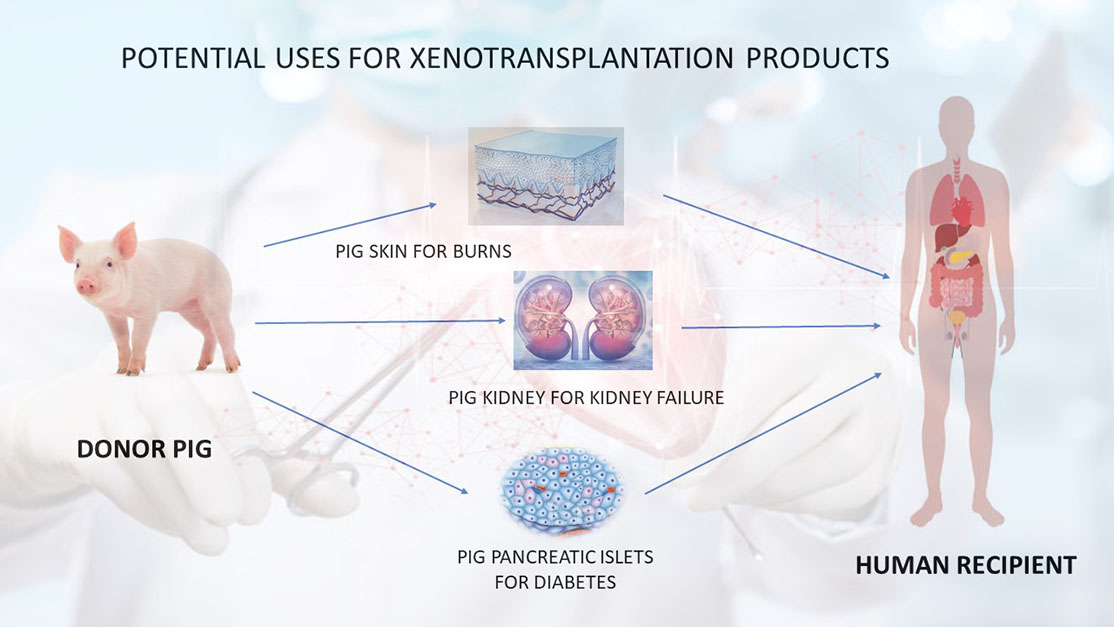

Researchers have developed chimaeras, whose bodies are a mix of cells from diverse species, in order to study human disease and find effective treatments. In fact, the most common organisms used to make chimaeras are mice, rats, pigs and monkeys, which all share a significant number of homologous genes with us.

However, chimaeras are not always man-made, as there are at least three examples of already existing human chimaeras:

- When a foetus absorbs its twin

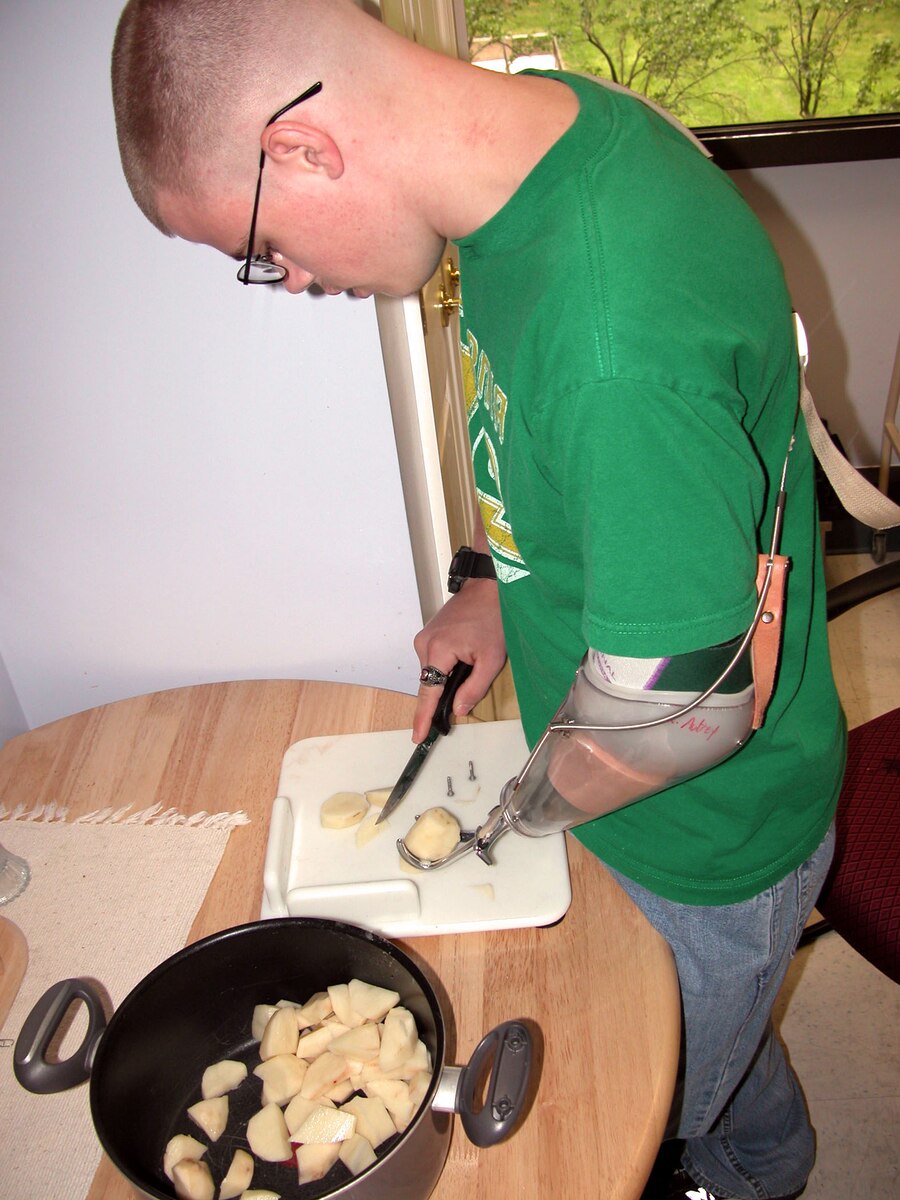

- When a patient undergoes a bone marrow transplant – e.g., to treat leukaemia

- When a small fraction of cells are from someone else, so-called “Microchimerism”

1) When a foetus absorbs its twin

This occurs during a fraternal pregnancy when one embryo dies very early, and the remaining one “absorbs” some cells from its twin in the womb. Therefore, the remaining foetus has two sets of cells: its original and the one acquired from its twin. These individuals very often do not even realise they are a chimaera.

People with this form of chimerism very often do not even realise they are a chimaera because they can appear entirely normal. Most of the time, this is discovered by accident, and makes this particular phenomenon very difficult to quantify. More rarely, individuals show visible signs, such as diverse eye colours, patches of skin of different shades, or even a mixture of female and male cells which can cause abnormalities in their reproductive organs.

2) Bone marrow transplant

Human bone marrow contains haematopoietic stem cells, which give rise to all types of blood cells in our body (e.g., white and red blood cells). When a person undergoes a bone marrow transplant, their own bone is destroyed and replaced with a new one from another person, therefore acquiring “foreign” blood cells for the rest of their life. In fact, these haematopoietic stem cells are genetically identical to those of the donor but are different from the rest of the patient receiving the transplant!

3) Microchimerism

This phenomenon seems to occur in almost all pregnant women (at least temporarily), as a very tiny number of cells from the foetus migrate into her blood and travel to diverse organs.

In 2015, researchers took samples on 26 women from their kidneys, livers, spleens, lungs, hearts, and brains. Results showed that all women, who had all been carrying sons, had foetal cells in all of these tissues, as these contained a Y chromosome (found only in males).

Another study in 2012 found foetal cells in 63% of the brains of 59 women ages 32 to 101, including the oldest who was 94 years ago. This could suggest that most mothers have cells from their babies growing in various parts of their body after pregnancy, and these cells can survive in a lifetime.

Final considerations

Before hearing Karen’s story during a university lecture held a week ago, I had no idea about the existence of human chimaeras. Her story quite shocked me as I couldn’t believe that she was not really the mother of her son, and therefore I decided to dig down the topic of chimaerism.

In the past, I had heard the term “chimaera” in some fantasy movies, as I am very passionate about this genre. However, I had never thought that this was possibly achievable in the real world, not even artificial chimaeras made in the laboratory.

Through this research, I learned that Karen’s story is not the only one of human chimaeras but there are many other instances. Thinking about what to write in the final considerations for this post, I had an epiphany, which inspired the title of this post: at least temporarily, we all are chimaeras!

We exchange living cells between us more often than we think, ranging from kissing or touching to sexual intercourse or a more invasive transplant! Yes, you read it right, but you probably didn’t know that even a very passionate kiss is able to transfer living cells from you to your partner and vice versa, making both of you temporary chimaeras! So I’ll be very careful the next time I choose who I’ll kiss …

Now, I recognise that chimaerism can come in various forms and quantities. More often, we contain only a few living cells from another person, and more rarely a single person can be a fairly equal mix of cells with distinct sets of DNA.

Building the first layer of knowledge on a completely new topic has completely challenged my previous understanding. I learned that hearing something for the first time can be quite shocking at first but I should make use of this experience positively to expand my views and opinions, rather than as a way to discourage myself. In the future, I will keep this positive attitude to get to know new topics, which could completely challenge the knowledge I have just acquired!

References:

1. Scientific American article written by Rachael Rettner, LiveScience on August 8, 2016

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/3-human-chimeras-that-already-exist/

2. MCSM RAMPAGE article written by Fariha Fawziah on January 31, 2017

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70056327/kidney_cropped.0.jpg)

This is an initially reflective and well researched blog showing how you have chosen to explore the emerging field of…

This is a good attempt at a blog, where you reflect on your recent learning at a lecture/workshop to describe…

This is a fair to good blog, reflecting on your recent learning in some of your modules. You provide a…

This is an engagingly written and reflective blog focussed in general on ethics in medicine. You might improve by citing…

This is a good and well written an presented blog on an original subject - biofilms on implants. You explain…