Immortal cells

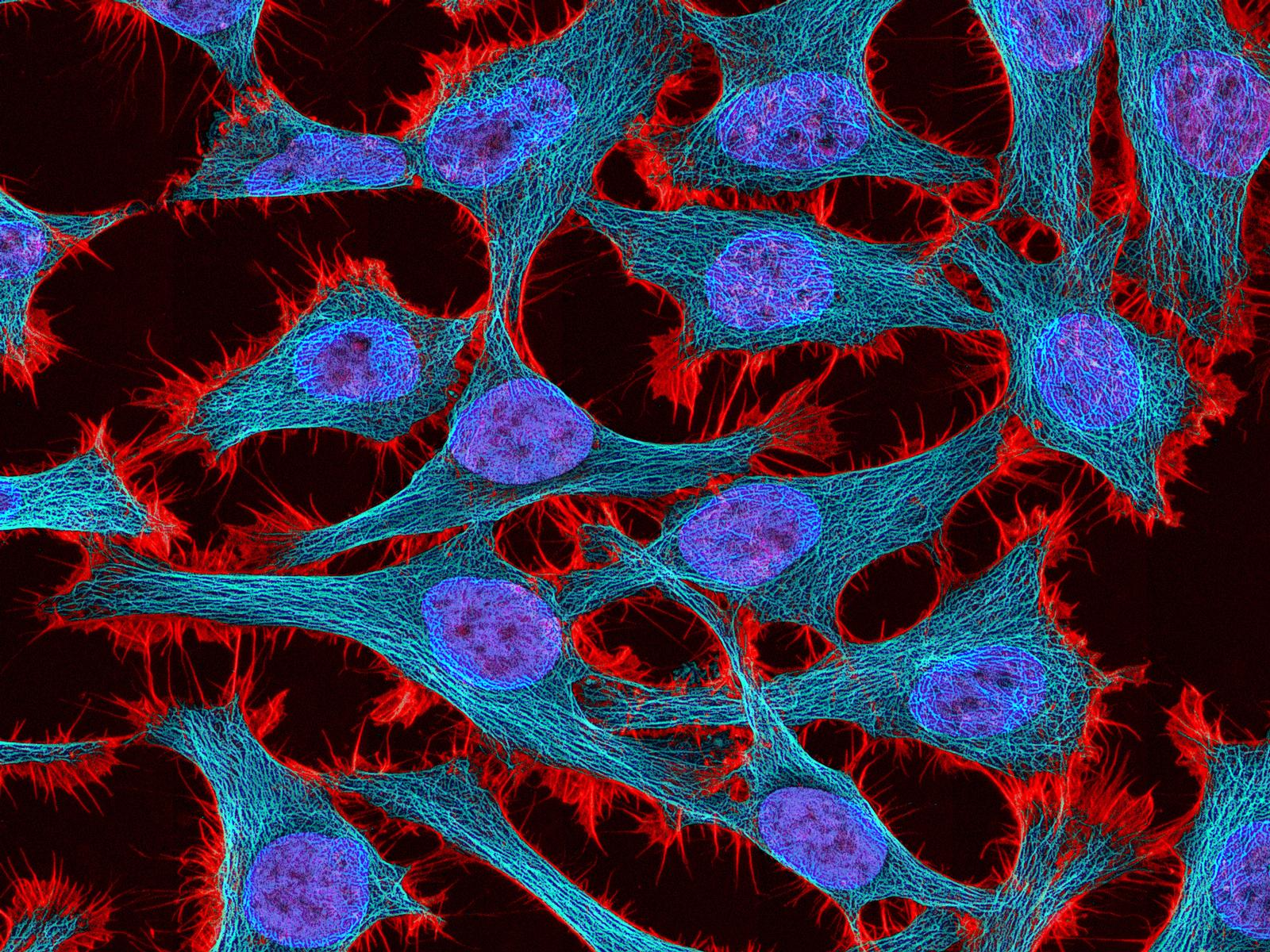

I recently read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot1; the remarkable story of an American woman whose cervical cancer was used to make the first immortal cell line, HeLa. In vitro cell research is normally constrained by the Hayflick limit2; cell lines die out after a few days. Lacks’ cancer was so aggressive that its cells could divide indefinitely, providing an invaluable biological material still used today. Incredibly, few know her name. The cells were used without her knowledge or consent, and her family knew nothing for twenty years.

This story raises important questions about human tissue ownership, notably: who owns medical waste, and can it be sold? Skloot heavily implies that the Lacks family should be compensated for Henrietta’s cells, but I’m not sure it’s so simple.

Tissue ownership in the UK

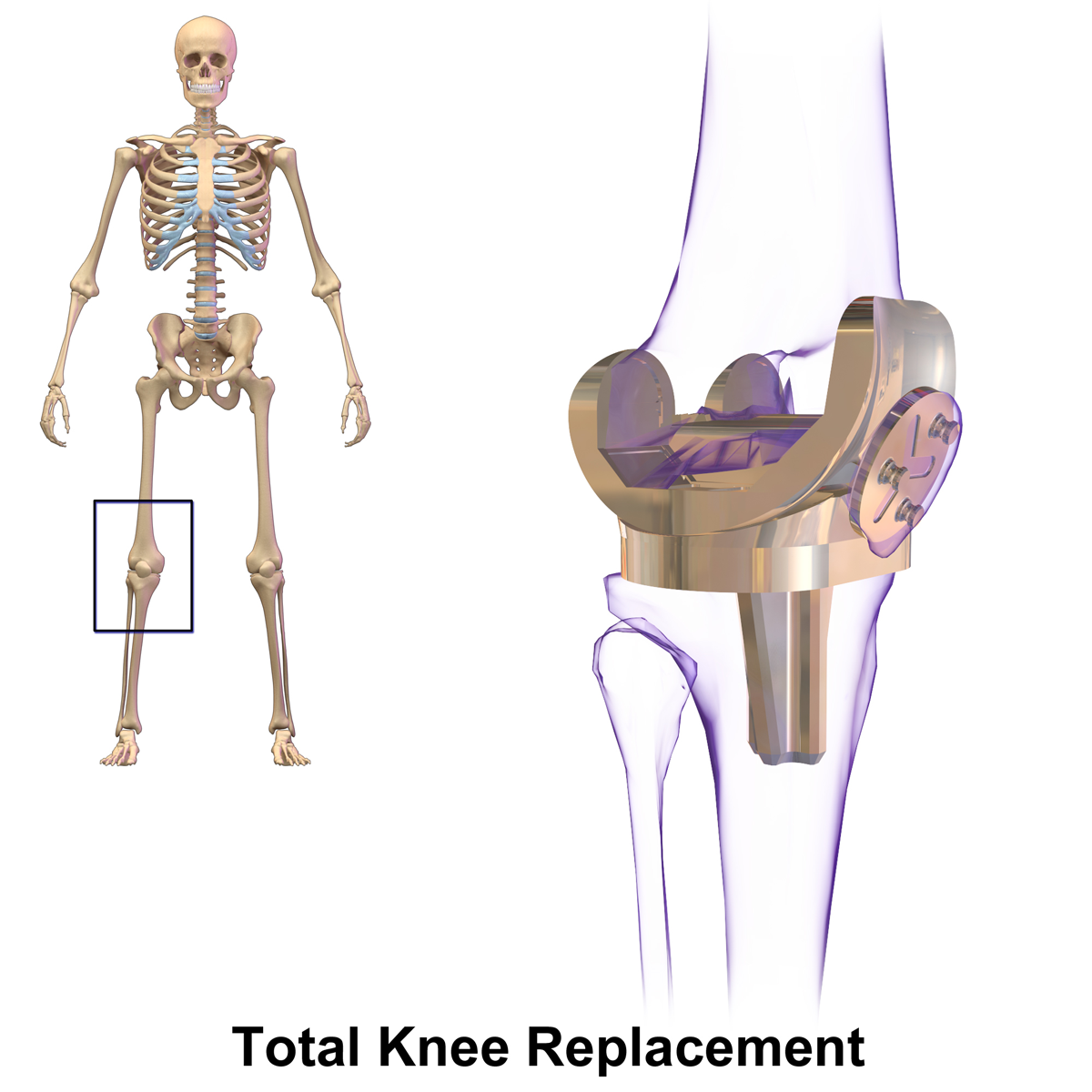

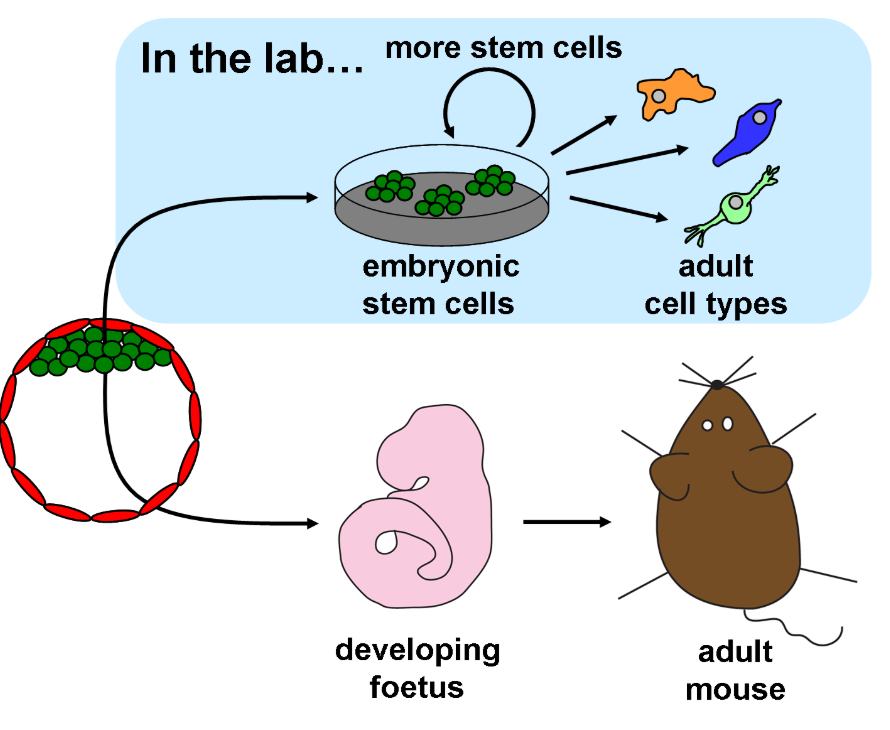

My friend works for the Southampton Imaging4 group and routinely uses femoral heads, leftover from hip replacement surgery, in his research. Recently introduced to tissue ethics, I had several questions for him. My Gran had a hip replacement – are scientists experimenting on her bone? Could they extract stem cells from the marrow and make a cell line like HeLa?

Thankfully, the Human Tissue Act 20045 (HTA) restricts research on tissue to licensed labs and requires informed consent from all donors. My friend assures me that strict protocols are followed, from surgery to the lab to disposal, and that his lab must comply with the Declaration of Helsinki6.

What does this mean for Lacks’ family?

Henrietta Lacks was treated unethically. Her cells should not have been used without her consent, violating her dignity when she was extremely vulnerable. Furthermore, it’s now possible to sequence HeLa’s genome, raising concerns about Lacks’ and (her family’s) privacy. Unfortunately she died in 1951, before widespread adoption of informed consent as best practice.

In her book, Skloot implies that Lacks’ family should be paid for the cells. It’s important to note that HeLa cells are not full organs, nor were they healthy – if not for their scientific usefulness they would have been deemed medical waste. In the US it is illegal8 to sell one’s organs, but consent and payment law for other tissue is more permissive than in the UK, where selling human tissue is banned.

I strongly support the UK position that selling human tissue for money, regardless of purpose or usefulness, is unacceptable. Tissue derived from a person’s body deserves to be treated with more dignity than a mere commodity.

Even if the act of selling one’s own tissue were ethical, a culture that allows it is not. It would encourage objectification of the human body and provide incentive for organ theft. Nobody should have to resort to selling their tissue. Meixuan Li’ 9 wrote a post exploring this concept taken to a dystopian extreme; prisoners exchanging their organs for reduced sentences. The very idea is abhorrent.

This is why, while Henrietta Lacks was wronged, her family should not be financially compensated. Payment for human tissue, even retrospectively, is morally unacceptable.

Sources

- Skloot R. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Crown Publishing Group (2010) ↩︎

- Hayflick’s handy guide to immortality and cell senescence. The Genetics of Basic Things and Stuff. 30th November 2022 (cited 24th March 2025). Video: 5:13 min. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w5SBZOa_qAg ↩︎

- Immortal Cells Turn 96. SciShow. 1st August 2016 (cited 20th March 2025). Video: 4:41 min. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXY6-wLesYY ↩︎

- Southampton Imaging. University of Southampton (cited 21st March 2025). Available from: https://www.southampton.ac.uk/research/institutes-centres/southampton-imaging ↩︎

- Legislation. Human Tissue Authority (cited 21st March 2025). Available from: https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-professionals/codes-practice-standards-and-legislation/legislation ↩︎

- WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving Human Participants. World Medical Association. 2024. (cited 21st March 2025). Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/ ↩︎

- Marc Silver. A New Chapter in the Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. National Geographic. 2013 (cited 21st March 2025). Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/130816-henrietta-lacks-immortal-life-hela-cells-genome-rebecca-skloot-nih ↩︎

- Can you sell organs in the United States? Donor Alliance; Tissue and Organ Donation. 2025. (cited 21st March 2025). Available from: https://www.donoralliance.org/newsroom/donation-essentials/can-you-sell-organs/ ↩︎

- Li M. Prisoners ‘Donating’ Organs for Sentence Reduction: Should the Punishment Fit the Crime? 12th March 2025 (cited 21st March 2025). In: Engineering Replacement Body Parts 2024-2025. Available from: https://generic.wordpress.soton.ac.uk/uosm2031-2025/2025/03/12/prisoners-donating-organs-for-sentence-reduction-should-the-punishment-fit-the-crime-2/ ↩︎

This is a good blog. It nicely demonstrates a good understanding of organ-on-a-chip technology and clearly explains its purpose and…

This is a good blog, very engaging with a good backgroud to 3D bioprinting. You could improve your blog with…

This is a good, very interesting blog about necrobotics. It explores the idea of necrobiotics which is fairly new approach…

This is a good blog. You introduce the reader to the topic of prosthetics and bionic limbs in a very…

This is a good blog introducing hernia mesh benefits and drawbacks. You create a narrative in this blog, which showcase…