During the stem cell debate workshop, I argued in favour of extending the 14-day embryo rule for the sake of the exercise. However, when asked about my true stance, I realised I didn’t have a clear answer. I felt conflicted because, while I didn’t condemn other researchers using embryos, I would never want to handle them myself. I have always strongly believed in human life – even the potential of human life. The thought of taking away this potential makes me feel very uneasy. This made me question whether I was simply unwilling—or perhaps unable—to extend my personal morals to others. I set out to discover more to help me come to a conclusion…

Why are embryos being used and where do they come from?

First, I strived to find out a little more about where the embryos are sourced and what is being done with them. I learned they are mainly derived from excess in-vitro fertilization (IVF) embryos and are donated for research purposes with informed consent. Strict regulations, such as the 14-day rule, limit research to early developmental stages before formation of the primitive streak. I also learned embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are studied for their potential in regenerative medicine, treating conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injuries, and heart disease.

So should we ban embryo testing?

Based on this information, I cannot say I’d support a complete ban. Excess embryos created for the sake of IVF should not be simply disposed of. This would be wasteful. Furthermore, lifesaving research has been done using embryonic stem cells. How could I condemn the loss of potential life if it means existing life has to suffer?

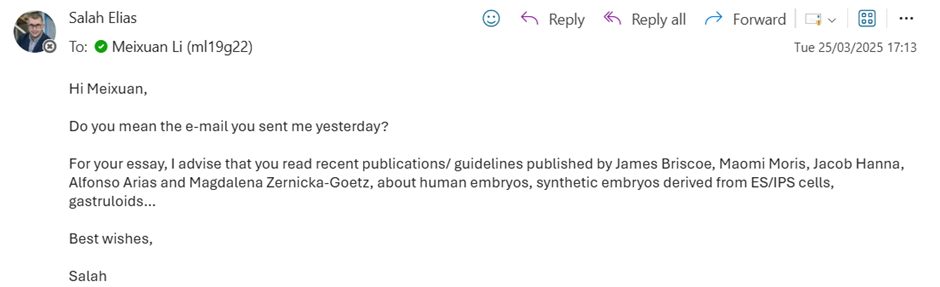

I then reached out to Dr Salah Elias who works with embryonic stem cells to ask for his opinion from an academic standpoint. While he did not directly share his own beliefs, he directed me to some useful recent publications:

The researchers mentioned in Dr Elias’ email are involved in synthesis of synthetic human embryos. Although they are not truly “synthetic” as they originate from embryonic stem cells cultured in the laboratory, they require a much smaller number of traditional embryos and therefore may be much more ethical as well as more readily available.

So shall we extend the 14-day rule?

Okay, so I’ve ruled out a complete ban, but how has Dr Elias’ papers influenced my opinions?

First, I must mention my research that led me to the He Jiankui Affair (2018) where I was horrified to learn Jiankui edited embryos during IVF using CRISPR-Cas9 technology and implanted them into a mother, resulting in the birth of twins Lulu and Nana.

This brought up the worry that extending the rule sets a precedent for continuous boundary-pushing, potentially leading some scientists to believe they have the right to create and bring a whole child to birth in the name of science. However, upon further reflection I do not think this incident was the result of lax boundaries – the laws were still in place, Jiankui just chose to break them. Furthermore, Jiankui was punished severely – he was sentenced to three years in prison, fined 3 million yuan and banned from working in reproductive medicine, reassuring me those who overstepped these laws would never be praised no matter how “revolutionary” their work proved to be.

While this realisation eased me a little, with the possibility of synthetic human embryos I do not believe it is necessary currently to extend the 14 day rule. By maintaining this rule and finding alternative approaches, we uphold a clear ethical framework that respects the potential of human life while still allowing for valuable research in early development and regenerative medicine. Until there is a compelling and widely accepted reason to extend this limit, I believe it is both responsible and reasonable to continue adhering to this boundary.

This is a good blog. It nicely demonstrates a good understanding of organ-on-a-chip technology and clearly explains its purpose and…

This is a good blog, very engaging with a good backgroud to 3D bioprinting. You could improve your blog with…

This is a good, very interesting blog about necrobotics. It explores the idea of necrobiotics which is fairly new approach…

This is a good blog. You introduce the reader to the topic of prosthetics and bionic limbs in a very…

This is a good blog introducing hernia mesh benefits and drawbacks. You create a narrative in this blog, which showcase…