Back in November 2024 I suffered a knee cap dislocation whilst playing a game of 7 a side football. After being sat in pain in Southampton General hospital’s A&E department for hours, unsure of what was next, my thoughts turned to all those facing this pain on a daily basis. One in four adults over the age of 55 report experiencing chronic knee pain, with an estimated 5.4 million people in the UK affected by knee osteoarthritis alone. It is not just older individuals affected by knee pain, however. Injuries to the knee occur at an average incidence rate of around 2.5 per thousand, with the highest rate of incidence occurring amongst 15-24 year olds. Overall, an estimated 8 million people in the UK are impacted by regular knee pain. As a result, over 100,000 individuals undergo either a total or partial knee replacement each year. Thus, it is essential to understand the evolution of this technology and how it can continue to improve through further innovation.

Evolution of knee replacements

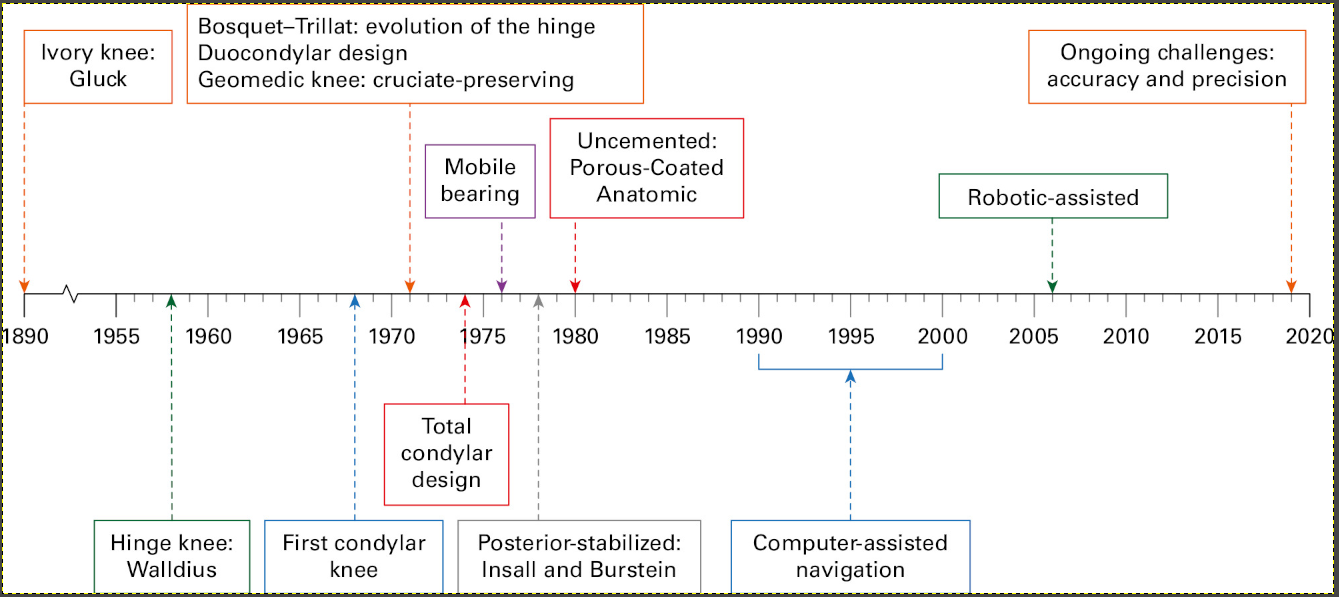

This is a timeline of all the major knee replacements that have been developed from the 1890s to today.

The first knee replacements were developed by a man named Theophilus Gluck, and were made from ivory before being fixed into place using plaster of Paris. These failed drastically due to inadequate fixation as well as frequent infections. The next major innovations weren’t made until 1958 with the advent of the hinge knee, made from cobalt chrome, by Walldius.

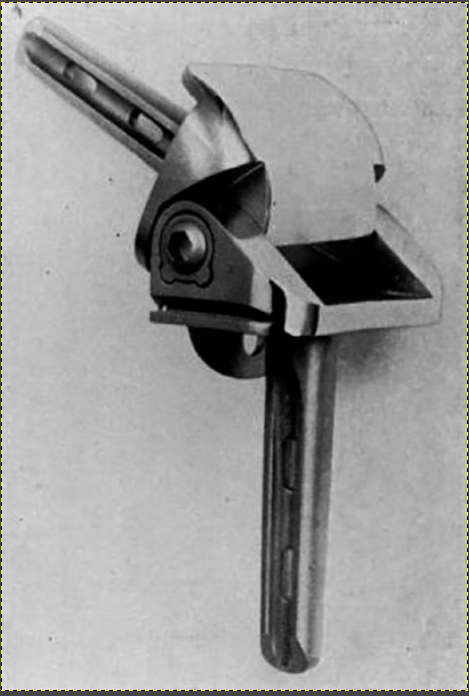

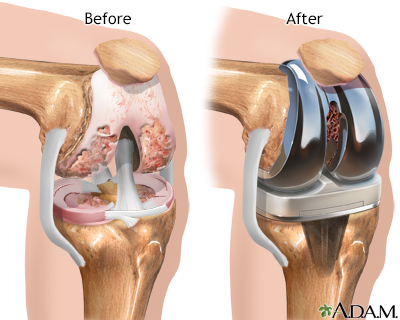

The knee replacement above, developed by Walldius, was an improvement on earlier models but is still considered rudimentary. The solid metal knee lacked any compressive abilities and was only able to pivot in one direction. Consequently, whilst pain in the knee was reduced, stress was created in the lateral direction and patients were unable to fully return to normal life. This model was followed by the development of Geomedic prostheses in the 1970s- also known as condylar knees. These allowed for the preservation of the both cruciate ligaments-. a major advancement. This allowed people who suffered with daily pain to eventually return to a pain free life. Unlike with Walldius’ replacement, most patients were able to perform a wide range of activities that they engaged in prior to surgery, giving rise to a better quality of life.

The image above shows a computer generated image of a knee that has been worn down (left) and what the knee would look like after the installation of a Geomedic prosthesis (right).

https://www.arthritis-health.com/types/osteoarthritis/surgery-knee-osteoarthritis-video

This video explains how surgeries have changed since the invention of Geomedic prostheses, aiming to reduce the impact of surgery on patients.

Whilst the invention of the condylar knee marks a significant improvement in knee replacement technology, there still remain several drawbacks: This knee only has a lifespan of 25 years, meaning that patients may need several surgeries in their lifetime. This presents a particular challenge to patients who may be older when the replacement deteriorates, as the risks associated with surgery increase. Additionally, a long recovery period is still associated with this surgery and replacement type, some patients never reaching full recovery. Finally, whilst patients can return to most daily activities such as walking, higher intensity activity is still not possible. This means that sports and an active lifestyle are difficult- often impacting the patients’ mental health negatively. Further research into new alternatives is essential to managing these issues. We have seen before how innovation can improve the options available to patients. Now, more than ever, the resources and technologies exist to create a new form of knee replacement and unlock new possibilities for those who receive them.

References

Beeston, A. (2022) Knee replacement: how to reduce ongoing pain?, NIHR Evidence. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3310/nihrevidence_53522.

Chronic knee pain | The BMJ (no date). Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/335/7614/303 (Accessed: 28 March 2025).

Mallen, C.D., Peat, G. and Porcheret, M. (2007) ‘Chronic knee pain’, BMJ, 335(7614), pp. 303–303. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39231.735498.94.

Patel, N.G. et al. (2019) ‘50 years of total knee arthroplasty’, Bone & Joint 360, 8(3), pp. 3–7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1302/2048-0105.82.360688.

The State of Musculoskeletal Health (no date). Available at: https://versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/data-and-statistics/the-state-of-musculoskeletal-health/ (Accessed: 28 March 2025).

Yasen, S.K. (2023) ‘Common knee injuries, diagnosis and management’, Surgery (Oxford), 41(4), pp. 215–222. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2023.02.003.

This is a good blog. It nicely demonstrates a good understanding of organ-on-a-chip technology and clearly explains its purpose and…

This is a good blog, very engaging with a good backgroud to 3D bioprinting. You could improve your blog with…

This is a good, very interesting blog about necrobotics. It explores the idea of necrobiotics which is fairly new approach…

This is a good blog. You introduce the reader to the topic of prosthetics and bionic limbs in a very…

This is a good blog introducing hernia mesh benefits and drawbacks. You create a narrative in this blog, which showcase…