Imagine curing genetic diseases before birth. What if we could eliminate hereditary conditions, eradicate cancer or even design the perfect baby? CRISPR-Cas9, a revolutionary gene-editing tool, promises to alter DNA, with unprecedented precision. However, its immense potential raises complex ethical dilemmas.

What is CRISPR-Cas9?

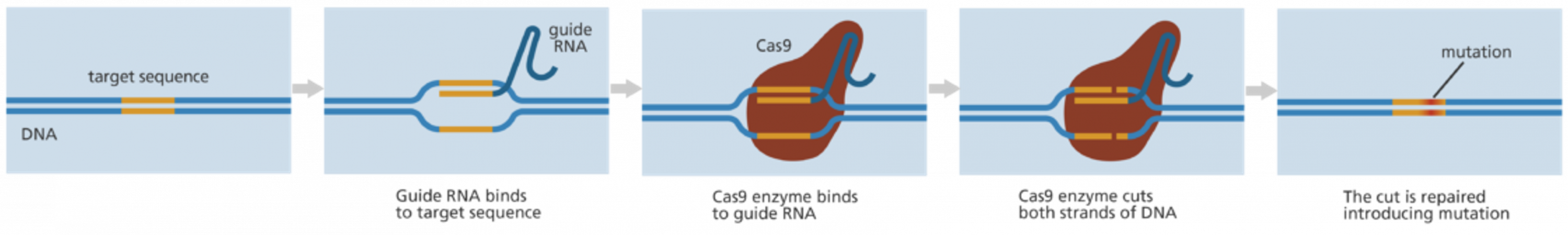

CRISPR-Cas9 is the most precise and efficient gene-editing technology available. Originally part of microbial immune systems, it has been adapted for genetic manipulation. The DNA is cut at specific locations, allowing genes to be added or replaced. Unlike previous techniques, CRISPR is faster, cheaper and more accurate with applications in disease treatment, immunity enhancement and even human enhancement. However, clinical applications remain in early stages, focused on animal models and isolated human cells.

As some with a family history of genetic conditions, I find hope in CRISPR’s early success in treating diseases like Sickle Cell Anaemia. Somatic gene editing, which treats disease in individuals, holds great promise. However, germline editing remains illegal due to ethical concerns, making the dream of eradicating genetic diseases from family lines a distant vision [1].

The self-proclaimed Chinese Darwin

In 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui made headlines using CRISPR-Cas9 to genetically modify twin embryos, Lulu and Nana, claiming to make them HIV-resistant. His experiment targeted the CCR5 gene, which also plays a role in immunity against West Nile virus and severe flu. Reports suggest the gene editing was incomplete in one twin, raising concerns of long-term health risks.

He’s work was neither curative nor medically necessary – IVF procedures had already prevented the risk of HIV transmission. Some scientists speculated disabling CCR5 could enhance cognitive intelligence, shifting the experiment from therapeutic to human enhancement. Lacking transparency and ethical approval, in 2019, He was sentenced to 3 years in prison [2].

Since his release, he has resumed research, calling himself the ‘Chinese Darwin‘; whilst critics label him ‘Frankenstein’. Unapologetic, he continues advocating for gene editing in Alzheimer’s and cancer research. His presence on social media fuels debate: is he a visionary or an unchecked egotist?

The ethical debate

Scientific progress comes with risk. Critics warn of unknown long-term effects, unintended consequences and regulatory challenges. Most diseases are multigenic, but CRISPR-Cas9 targets single genes, limiting its effectiveness. Ethical concerns revolve around the potential of human enhancement, inequality and whether parents can truly consent to risks. Even He Jiankui admitted designer babies would be difficult to control.

Despite concerns, I support scientific progress. Why allow suffering if we have technology to prevent it? Eliminating genetic diseases would ease demand on healthcare and benefit society. Regulation, not rejection, is the key – gene editing is here and we must adapt to its evolving role in medicine. Balancing innovation with ethics will determine its future.

Looking ahead

Somatic gene editing is legal in many countries and holds promise for treating disease. However, germline editing remains controversial. As some nations ease restrictions, we may see a global divide in human genetics.

While I believe gene editing has a guaranteed future and remarkable benefits, I worry that without proper regulation, we will face a societal divide. One group will be enhanced, tailored for specific roles with predetermined superhuman qualities, from intelligence to athletic prowess. The other group will be us, free to make our own choices but facing a constant struggle to survive, and subject to natural selection.

Gene editing could revolutionise medicine, but how we choose to use it will determine whether it leads to progress or division.

References

[1] Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc [online]. 2013;8:2281-2308. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.143

[2] Raposo VL. The First Chinese Edited Babies: A Leap of Faith in Science. JBRA Assist Reprod [online]. 2019;23(3):197-199. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20190042