“We don’t appreciate what we have until it’s gone.” This phrase resonated deeply with me during the lecture on joint replacements. We often take for granted the ability to move and stand without pain—until one day, we can’t. Millions of lives have been transformed by the invention of knee replacement, restoring people’s movement but also their independence. But what are the challenges of these replacements and what does their future look like?

Evolution of knee replacements

The idea of replacing damaged joints isn’t new and has been around for hundreds of years where ancient civilisations experimented with rudimentary prosthetics. Modern knee replacement surgery, or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) however, only emerged in the mid-20th century. Advances in materials, surgical precision, and rehabilitation have meant that patients today can regain almost all lost function. Whilst these improvements have been greatly beneficial, there are still risks and limitations involved.

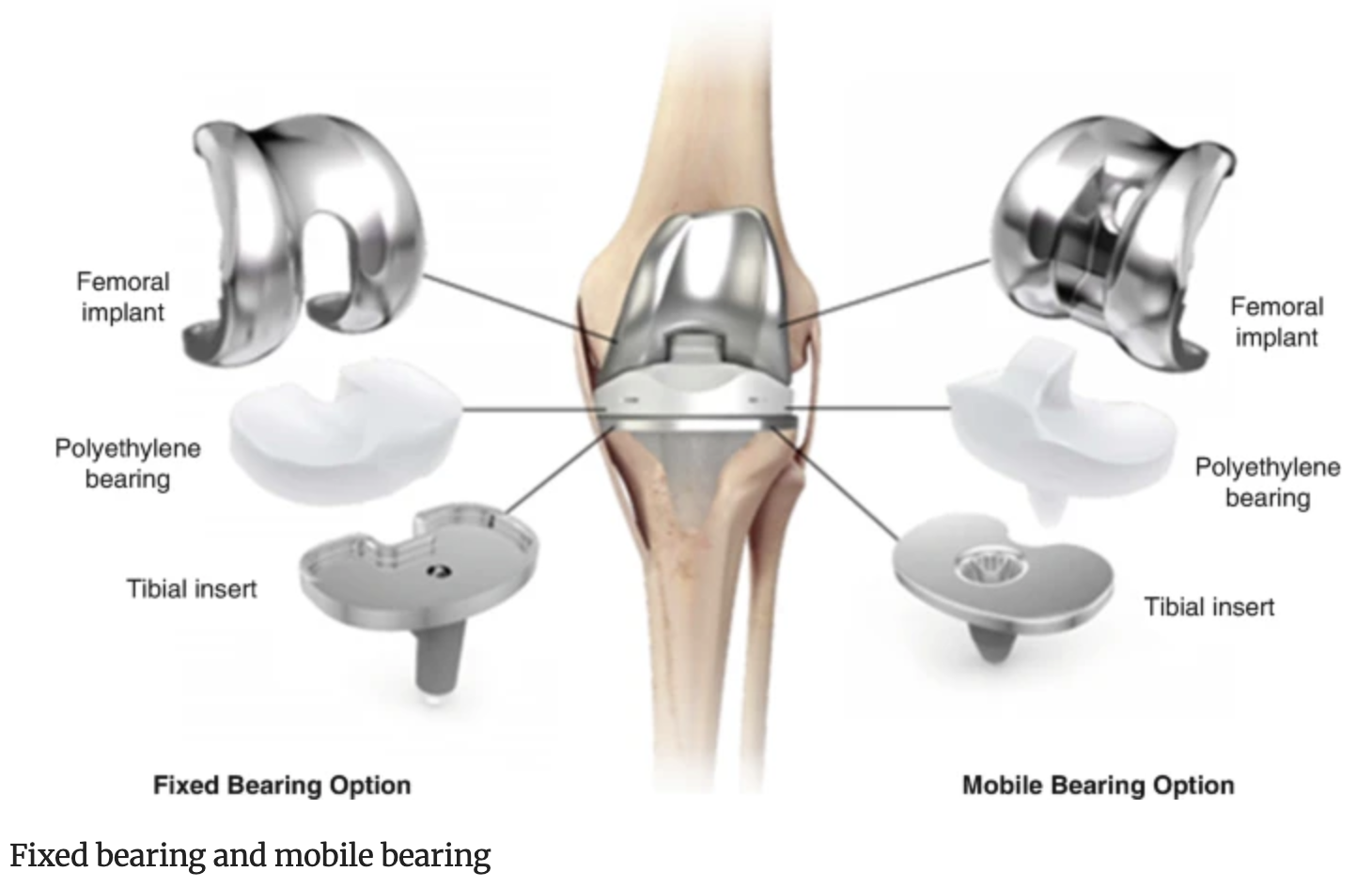

image: Fixed vs mobile bearing of knee replacements https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-8591-0_3

More Than Just a Mechanical Problem?

Engineering is at the core of a knee replacement where surgeons remove damaged bone and replace it with metal and synthetic components that are specifically designed to mimic the joint’s natural function. The real challenge however, is in how the body allows the artificial joint to work within our bodies, where ligaments, tendons, and muscles must adjust to the artificial joint, and imbalances in force distribution can lead to complications such as implant loosening. The risk of rejection is also prevalent as the body may recognise the implant as foreign, triggering low-grade inflammation that can affect the implant’s longevity.

As with any surgery there is the emotional and psychological side. How does it feel having to relearn simple movements such as walking? Regaining autonomy can be life-changing, but rehabilitation can be long and demanding.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite its success and widespread use, it still has its limitations.

- Longevity of implants: A knee prosthesis only lasts 15–20 years and so younger patients may require multiple complex surgeries.

- Access to prosthetics: Not everyone can afford a knee replacement. Is it right that orthopaedic treatments are more readily available to those with financial means?

- Surgical risks: Infections and rejection are still major risks.

In a recent BBC article from last year, Heather considered herself “lucky” to have had her left knee replaced after two years of pain. This article highlights a wider systemic issue in healthcare-availability. The question remains as how can we solve this?

This shows that there is still a long way to go when talking about this type of technology and highlights the need for continuous innovation in this area.

Future of Knee Replacements: Can We Do Any Better?

With recent advancements in areas such as 3D printing and robotic-assisted surgery, the future of knee replacements is still promising. One day, could we use cartilage grown in a lab to produce personalised implants? And could AI-driven rehabilitation programs increase patients’ recovery outcomes?

This lecture changed the way I think about joint replacements as a field that intersects engineering, biology, and ethics. It made me think about the the privilege of mobility and the importance of continuous innovation in medical technology.

This is a well researched blog with good use of multimedia and well structured. It would benefit from more reflection throughout, what did you learn, what are your opinions on some of the ethical considerations?