Mentioning chimeras tends to evoke images of the mythical monster, part lion, part goat, part snake. When human chimeras – someone whose cells are derived from two or more zygotes – were introduced at the beginning of the lecture series I wondered, given the difficulty we have preventing organ rejection after transplants, how do chimeras avoid it? Simply put, the immune system develops recognizing both sets of antigens as self but while looking for an answer I came across this:

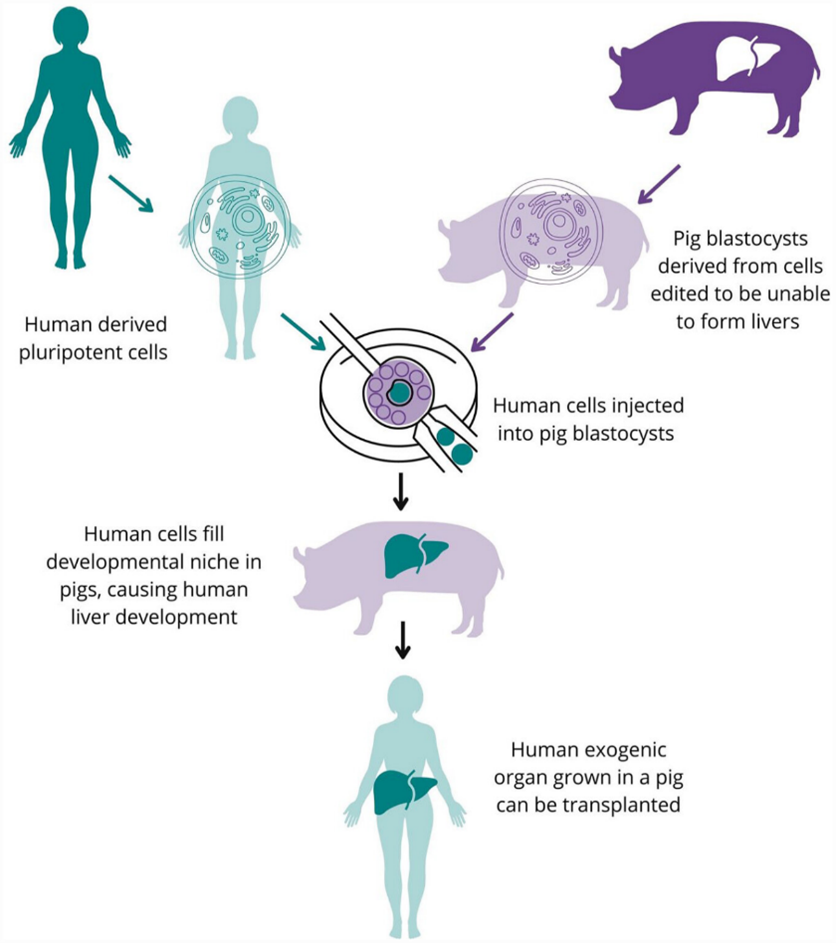

It was a jarring turn of phrase in a section talking about the potential of growing humanized organs in surrogate animals. As an idea I knew very little about it seemed like a promising concept but my own alarm at that phrasing prompted further reading. A brief outline of the process is given the diagram.

Why do we need to grow organs?

Before I go further into chimeric organs and the concerns raised by them, the problem this technique aims to solve should be described. This March there was around 8000 people waiting for organ donation in the UK. Between 1 April 2021 and 31 March 2022, 429 people died while on the transplant waiting list. Medical care and safety systems are improving which may reduce the number of donors (who are usually deceased). Other methods for reducing this shortage –therefore other competitors for funding – include expanding the donor pool and increasing the utilisation of less ideal donors but this can reduce the success of transplants.

So humanised organs from chimeras could bridge this gap and hold the potential to solve the problem that brought my attention to chimeras in the first place: immune rejection. Anti-body mediated rejection can cause organ transplants to fail when the recipient’s immune system detects the donor organ as a foreign body and attacks it. In chimera donors the organ is grown from induced pluripotent stem cells of the patient so should possess the same antibodies and not be rejected. Sounds good so far…

But whereas human donors (or their relatives) make an informed decision on whether to donate, chimera donors would involve creating, growing and killing animals to produce human organs. A multitude of animals are already raised and slaughtered for the food industry though this is not without contention.

Ethical issues

Concerns raised include issues surrounding identity, transspecies infection, economic considerations and the allocation of pig vs. human organs. The latter is a fascinating conundrum whose shape will depend on comparative efficacy and cost of the two methods. Will chimera organs be the cheap second tier option or the premium and should either scenario be allowed? There is also concern that giving pigs human cells could confer enhanced cognitive abilities that allow pigs human-like thought.

The technology is not ready yet so will require further time and funding that could be allocated to, for example, preventative treatments. A heart xenotransplant has been attempted that used a pig edited with human genes -not whole human stem cells- that aimed to reduce the immune response inserted but the heart was rejected.

Conclusion

Chimeric organ donation has the potential to alleviate human suffering but at the cost of animal welfare, sparking debate. Emotional responses against chimeras may be rooted in the monstrous associations of the name itself and expressed as going against nature. From a consequentialist view the benefit to humans could outweigh the exploitation of animals but developing the technology will involve considerable risks to people. While researching this my opinion has swung between for and against but settled on cautious support for chimeric organs.