The idea of replacing or enhancing parts of the human body has become a recent fascination. The fusion of science, engineering and medicine in prosthetics and implants is both inspiring and unsettling. On one hand, restoring mobility to an amputee or alleviating chronic pain through hip replacement is an incredible medical achievement. But on the other, I find myself questioning at what point does medical restoration become human enhancement? Are we simply fixing what is broken, or are we redefining what it means to be human?

Throughout the module, I have explored both scientific advancements and ethical dilemmas of biomedical engineering. I often reflect on the implications of these technologies. Would I, for instance, replace a healthy joint to improve athletic ability if given the chance? If prosthetics surpass natural limbs in function, how would that redefine ability and disability? these questions challenge my understanding of medicine, fairness and human identity, making me reconsider the fine line between restoration and augmentation.

The power of prosthetics and replacements

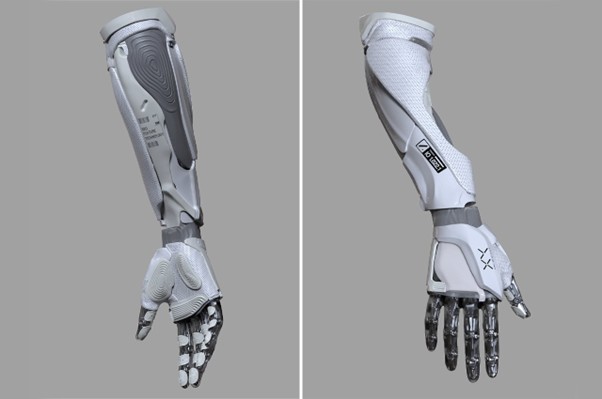

Modern prosthetics are not just about replacing missing limbs or functions – they incorporate bionic technology, neural integration and even sensory feedback. I recently read about individuals who can control prosthetic hands with signals from their brains, an innovation that would have been considered science fiction just decades ago. Similarly, joint replacement technology has evolved beyond traditional metal implants – biocompatible materials, smart implants and 3D-printed custom joints are transforming the field. After speaking with friends who have undergone joint replacements, I have seen firsthand how these advancements restore independence and mobility. However, their experience also highlighted the divides in healthcare – long waiting lists and financial barriers leave many suffering while others access cutting-edge treatments with ease.

Neural implants: restoring memory or redefining humanity?

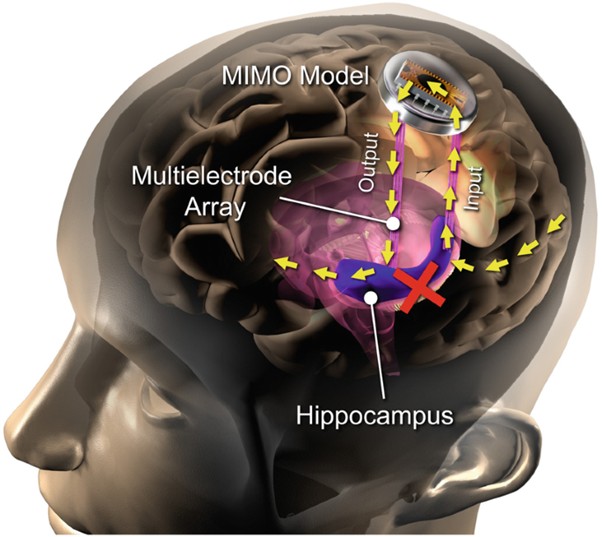

Beyond physical mobility, biomedical engineering is now venturing into cognitive function. Neural implants in the hippocampus – designed to restore memory to people with brain injuries or neurodegenerative diseases – are becoming a reality. [3] These implants mimic the brain’s natural process, helping those with memory loss regain the ability to form and retrieve memories. With this technology holds enormous potential for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, but I cant help but wonder about its broader implications. If memory can be artificially restored, can it also be enhanced? Could we eventually ‘upload’ knowledge directly into the brain, blurring the line between natural intelligence and artificial augmentation.

The ethics and inequality of enhancements

While I admire these breakthroughs, I cannot ignore their ethical implications. One of my greatest concerns is accessibility – should life-changing medical innovations be available only to those who can afford them? Advanced prosthetics are often prohibitively expensive, meaning that some people must settle for outdated or limited options. To me, healthcare should prioritise functionality and accessibility over innovation purely for enhancement.

Beyond affordability, there is the question of fairness. If prosthetic limbs or implants become superior to natural human abilities, will those who can afford them gain an unfair advantage? Consider the case of Olympic sprinter Oscar Pistorius, whose use of caron-fibre prosthetic legs sparked debate over whether he had an advantage over able-bodied athletes. If enhancements continue advancing, could they lead to a society where ‘baseline’ humans are at a disadvantage? Would we accept an era where the wealthy could extend their lifespans or outperform others simply because they had access to superior biomedical technology.

References

[1] McNulty-Kowal, S. (2022) This prosthetic limb integrates smart technology into its build to Intuit and track each user’s movements – yanko design, Yanko Design – Modern Industrial Design News. Available at: https://www.yankodesign.com/2022/03/27/this-prosthetic-limb-integrates-smart-technology-into-its-build-to-intuit-and-track-each-users-movements/ (Accessed: 28 March 2025).

[2] Prosthetics through the ages | NIH MedlinePlus Magazine (2023) MedlinePlus. Available at: https://magazine.medlineplus.gov/article/prosthetics-through-the-ages (Accessed: 28 March 2025).

[3] Erden, Y.J. and Brey, P. (2023) ‘Neurotechnology and ethics guidelines for human enhancement: The case of the hippocampal cognitive prosthesis’, Artificial Organs, 47(8), pp. 1235–1241. doi:10.1111/aor.14615.

[4] Song, D. and Berger, T.W. (2018) ‘Hippocampal memory prosthesis’, Oxford Scholarship Online [Preprint]. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199674923.003.0055.