I remember the morning I rolled out of bed, barely in time to drag myself to my 9am lecture. ‘I’ll put on a podcast,’ I thought to myself. Something to engage the brain, as opposed to a listening to a jumble of lyrics meaning a whole load of nothing. As I wearily scrolled through the ‘Podcast Charts’ on Spotify, something caught my attention: ‘The Human Subject,’ by Dr Adam Rutherford and Dr Julia Shaw.

I expected an insightful discussion on medical advancements on humans, but what I didn’t anticipate was how deeply unsettling it would be. Instead, I heard about how real people (often marginalised groups) were being exploited for the sake of medicine. Being treated as disposable in the name of science felt like something from a dystopian novel.

What disturbed me most was that these experiments weren’t history. They were recent. How much has actually improved over time? I was forced into an painful truth: progress has a price, but not everyone pays it equally.

Unethical Experiments: Lessons from the Past?

Nazi’s and Nuremburg: The Illusion of Progress

One of the most notorious examples of unethical medical research, which I learnt about in both GCSE History and this module, was the Nazi experiments during World War II. Prisoners, constrained in concentration camps, were subject to horrific hardships one could even struggle to imagine: disease injections, surgery without anaesthesia and freezing experiments1, to name but a few. The justification? ‘It was in the name of science.’ 2

Ms. A, Age 83

Place of Persecution: Auschwitz

Dates: April 1943 to May 1945

“The experiment was done to me in Auschwitz, Block 10. The experiment was done on my uterus. I was given shots in my uterus and as a result of that I was fainting from severe pain for a year and a half. [Years later,] Professor Hirsh from the hospital in Tzrifin examined me and said that my uterus became as a uterus of a 4-year-old child and that my ovaries shrank.”

These brutalities lead to the ‘Nuremburg Code’ (1947), a set of 10 principles establishing informed consent; a fundamental rule in current medical ethics.3 This should have changed everything. But it didn’t.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study: Exploiting Racial Disparity

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972) emphasised that medical research exploitation wasn’t just confined to Nazi Germany. In this U.S governmental project, which took place in Alabama (a wildly racist area at the time, where lynchings and Ku Klux Klan activity was rife,) hundreds of Black men with syphilis were purposefully left untreated with the disease, even after penicillin became widely available.

And you know what was astounding? They were lied to. With the illusion of receiving free healthcare, and under the guise of treating them for ‘bad blood’; (a colloquial term encompassing anaemia, fatigue and other conditions) they were actually being used as experimental subjects, mimicking the vulnerable populations throughout history. As the syphilis progressed, patients were brutally subjected to bone deterioration and tumours. 4

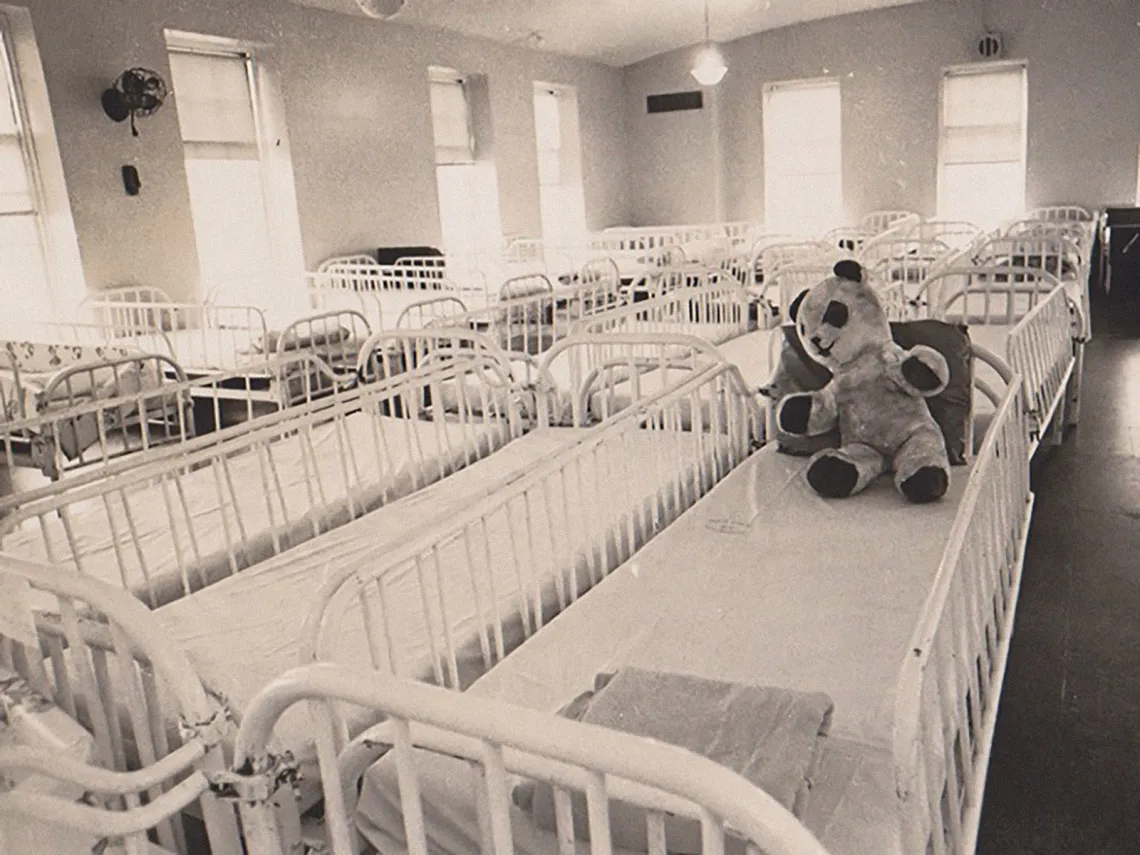

The Willowbrook Hepatitis Experiments: Abusing Disabled Children

Tuskegee wasn’t horrendous enough, it seemed. Lets take things even further. At Willowbrook State School, a facility for children with intellectual disabilities, researchers deliberately infected children with hepatitis, just to observe disease progression (1950-70).

This contributed to the already obvious stigmatisation of the children, many of whom were eventually reintegrated back into public schools. 5

The justification for this one? Given the unsanitary conditions, ‘they would’ve got it anyway.’ 6

An eerie phrase I couldn’t get out of my head. Is this not an easy justification for pharmaceutical companies, in the modern day, to test experimental drugs on vulnerable individuals?

Modern Clinical Trials: Endured Exploitation?

Today, drug companies conduct clinical trials globally, often in developing countries where healthcare is scarce. A win-win, no? Researchers get test subjects, and patients get access to treatment they couldn’t otherwise afford.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: many people enroll in these trials not with scientific intent, but through obligation.

Personal Privilege

I’m in the library, sitting behind my laptop, writing a blog. You’re also behind a screen right now. For us, it’s easy to debate what’s right and wrong in medical research. We can analyse historical cases, question consent, and critique clinical trials as much as we want. But simply having this discussion is a privilege.

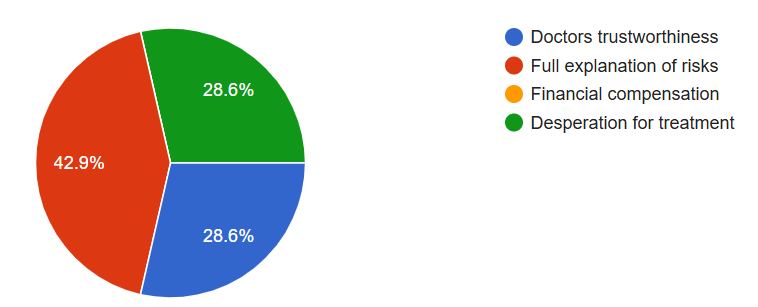

I asked my friends, all university students, “What factor would make you feel most comfortable participating in a clinical trial?”

Not a single person chose financial compensation as their top reason. People prioritise ethical transparency over monetary incentives when making medical decisions.

But that raises an important question: Would the results have been different if I asked people who couldn’t afford healthcare?

I have relatives in India, many of whom live in poverty. Posed with a life threatening illness, I don’t think they’d think twice about ethical implications of a clinical trial. For them, it’s not about contributing to scientific progress. It’s about survival.

Another thought struck me. Informed consent means nothing, if the only other option is death.

Its easy to see how pharmaceutical companies justify testing in uneducated, poorer countries. They can claim it’s ‘voluntary,’ all they want, but power imbalance is evident: the wealthy make the rules, and the desperate follow them. And this raises a plethora of questions:

- Do participants actually understand the risks? (If they can’t read consent forms, no.)

- What happens when the trial ends? (Many participants don’t get continued access to the drug that saved their lives.)

- Would these experiments be allowed in wealthier countries? (If not, why should they be acceptable elsewhere?)

Final Thoughts

I used to think laws were enough to prevent unethical research. Starting from the Human Subject, to my own research, I have learnt many things.

- Science doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s moulded by economics, power, and privilege.

- Ethical dilemmas aren’t black and white. People may enroll in trials because it’s their only option.

- We must question who benefits from medical progress. And who gets left behind.

As someone fortunate enough to discuss these ethics, I feel a responsibility to ask uncomfortable questions. Because if history has taught us anything, it’s that the cost of scientific progress is always paid by someone.

[A Beautiful Mind (2001). John Nash, a talented mathematician and schizophrenic, leaves his baby in a running bathtub. Deluded, he can't grasp the danger of his actions, putting his child’s life at risk. This moment is a raw depiction of Nash’s vulnerability, brilliance overshadowed by a mind that betrays him through invasive, unethical treatments he is subjected to.

His story mirrors a painful truth. The marginalized pay the price for medical progress. For those at the top, the breakthroughs come at the expense of those at the bottom, left to face the consequences of a system that claims to help, but often exploits, their fragility.]

References