Contents

Copy. Delete. Paste. Three words we all subconsciously think as we comb through text during our daily lives. Three words that I’ve been repeating endlessly as I spend countless hours cutting and pasting lines of code, desperately trying to make my third-year university project work. Combining the realisation of what an invaluable yet simple tool we have everyday access to and my studies in Biomedical Engineering, I began wondering if we could apply a similar gadget to our own DNA, removing any sequences we deem “undesirable” and replacing them with something of our choosing.

This led me to the discovery of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, also known as CRISPR, which allows us to do exactly that, opening up a world of opportunities to cure disease as well as further the abilities of other biotechnologies – you can read more about the potential of a fascinating combination of stem cells and CRISPR-Cas9 here!

How does it work?

See below a brief video which explains how CRISPR-Cas9 is capable of editing our DNA!

How could it be used?

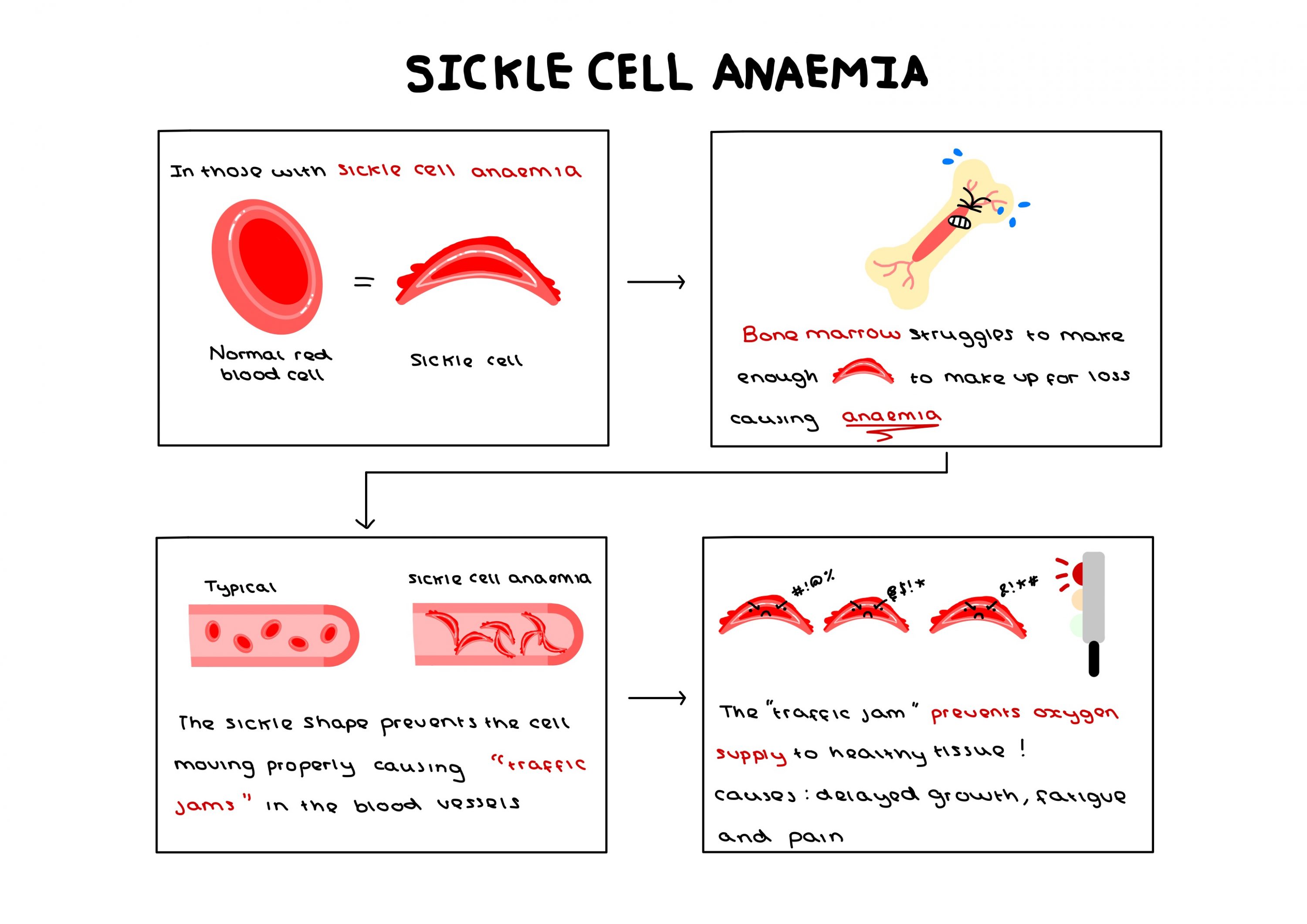

One potential application of CRISPR-Cas9 currently being investigated surrounds sickle cell anaemia, an incurable genetic disease with only expensive and harmful treatments available. The potential to undergo a singular procedure to completely cure this condition is revolutionary – a potential that could be applied to up to 8,000 more genetic mutations.

However, the capacity for this technology is so great that I find myself beginning to fear what it could be used to eradicate instead of simply treat. Concerns are already being raised by scholars with genetic differences, statements such as “our genetic conditions are not simply entities that can be clipped away from us as if they were some kind of a misspelled word or an awkward sentence in a document” being published in scientific news journals, highlighting that someone is still human despite their differences. The desire to completely remove a gene from society assumes that people with such genes are constantly suffering, their gene pool contaminated and inherently inferior.

Personally, I carry the genetic mutation for haemochromatosis, a condition that means I will most likely be subject to regular venesection in my later adult years. Whilst I have no affinity for my condition, viewing it as separate to myself and something that I would readily “delete”, having access to the support groups has shown me how it can bring people together and create a beautiful community – something that can make some feel positively connected to their condition. The idea that we could use CRISPR-Cas9 to not only treat genetic diseases but instead completely remove them from existence raises the question of whether this technology is a cure or a threat to these communities.

Ethical Parallels

A parallel can easily be drawn between the ethical issues surrounding the application of CRISPR-Cas9 in curing instead of treating genetic diseases and those restricting gene editing on embryos. As of March 2025, it is illegal to perform gene editing on embryos for reproduction in the UK, “designer babies” being labelled as a “ethical horrors waiting to happen” by news companies as profound as The Guardian.

As a society we must be careful as we toe the line between providing the best quality of life and removing people’s individuality, a line that could easily be crossed by both of these technologies. In the end, I struggle to distinguish the difference between editing an embryo’s genes to create what is considered an “ideal” baby, a process that is currently illegal, and “perfecting” the genes that somebody already lives with. Despite this, I also wonder whether it is truly ethical to leave somebody wishing for a cure when one is sat right within our reach.

But in the end, how would you feel if a fundamental part of what made you you could be so easily erased from existence?