Neuroprosthetic devices make use of the nervous system to enhance their ability to efficiently restore function to a part of the body, usually after an injury has occurred [1].

Some examples are [2]:

- Cochlear implants

- Prosthetic limbs

- Retinal implants

In this particular post I will concentrate on just these examples, explaining what they are and how they work, along with evaluating their risks and any ethical concerns surrounding their use.

Cochlear implants

What are cochlear implants?

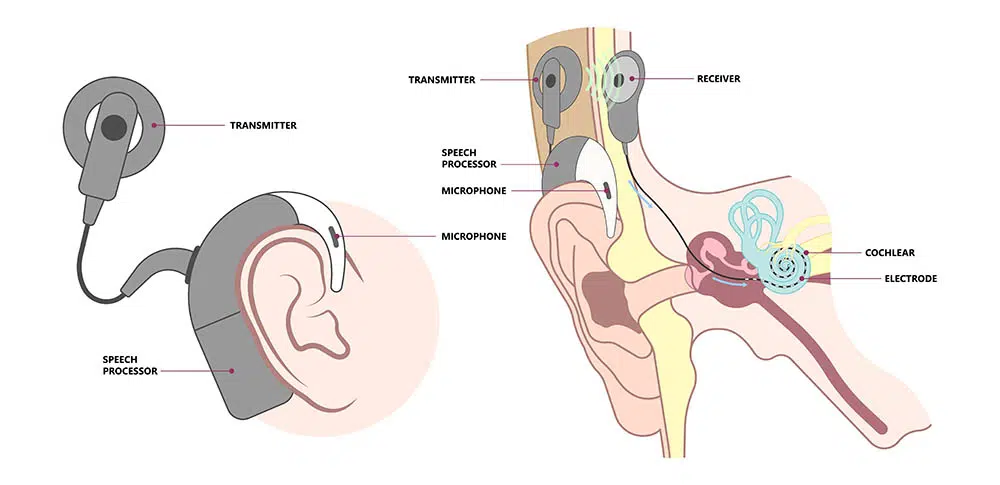

Cochlear implants are devices used to allow someone who is deaf or extremely hard-of-hearing to have a sense of sound. Part of the implant is external and sits just behind the ear and the other part is internal and is placed under the skin [3]. The implant picks up sounds using the external part of the device which are then received by the receiver under the skin. These are then converted into electrical signals which can be used to stimulate the cochlear nerve and therefore be understood as sounds by the brain [4].

Risks and ethical concerns with cochlear implants

There are many benefits to this type of device which generally improve the patient’s quality of life. Adults tend to benefit from the implant immediately and could have the ability to understand speech without lip-reading, make telephone calls and even perceive different types of sounds [6].

However, there are also some drawbacks to the implant. It is invasive and requires surgery, which comes with various risks such as damage to the facial nerve, infection and leakage of fluids (cerebrospinal and perilymph) [6]. In addition to the surgical risks, there are also some general risks involved: any hearing that was remaining could be lost, the implant could fail and lifestyle changes will need to be made to prevent damage and interference with the implant [6].

There is also an ethical debate involving the use of cochlear implants in deaf/hard-of-hearing children. There was an interesting discussion I found about this topic in an article by Byrd et al. [7]. The article talked about how some people in the Deaf community are sceptical about the devices and feel that they are not worth the risks involved. Additionally, lots of parents in the Deaf community wish to also bring up their children in the community, so that they can share their language, culture and unique experiences. Because of this, some parents will choose to not put their Deaf children through the surgery. However, it has been shown that it’s beneficial for a child to have the implant before 24 months of age to allow better development of speech and language, so in some cases this has raised questions about whether not giving a child the surgery should be considered neglect.

I think that it’s a very complex situation and each case must be looked at individually to determine what’s best for the child in that particular scenario. I also think it’s important that the parents are well informed about the risks and benefits of cochlear implants so that they are able to make the right decision.

Prosthetic limbs

What are neuroprosthetic limbs?

Neuroprosthetic limbs are replacement limbs that are connected to the nervous system allowing the person to control the prosthesis with their brain. For example, in bionic legs, electrodes measure the nerve activity from the person’s intention to move their leg and then a computer in the neuroprosthetic device uses these signals to move the prosthesis [8].

Issues with neuroprosthetic limbs

Due to the type of data collected to train and use these devices, there needs to be an evaluation of the safety of this data to protect it from hacking [9]. Since AI is often involved with these devices, there is bias involved that should be taken into consideration [9].

In my opinion, although there are still some concerns surrounding the use of these devices, the potential benefits by far outweigh the risks, so more research in this area would be beneficial. And as technology improves, as will AI and the ability to protect data, so these concerns could be eliminated in the future.

Retinal implants

What are retinal implants?

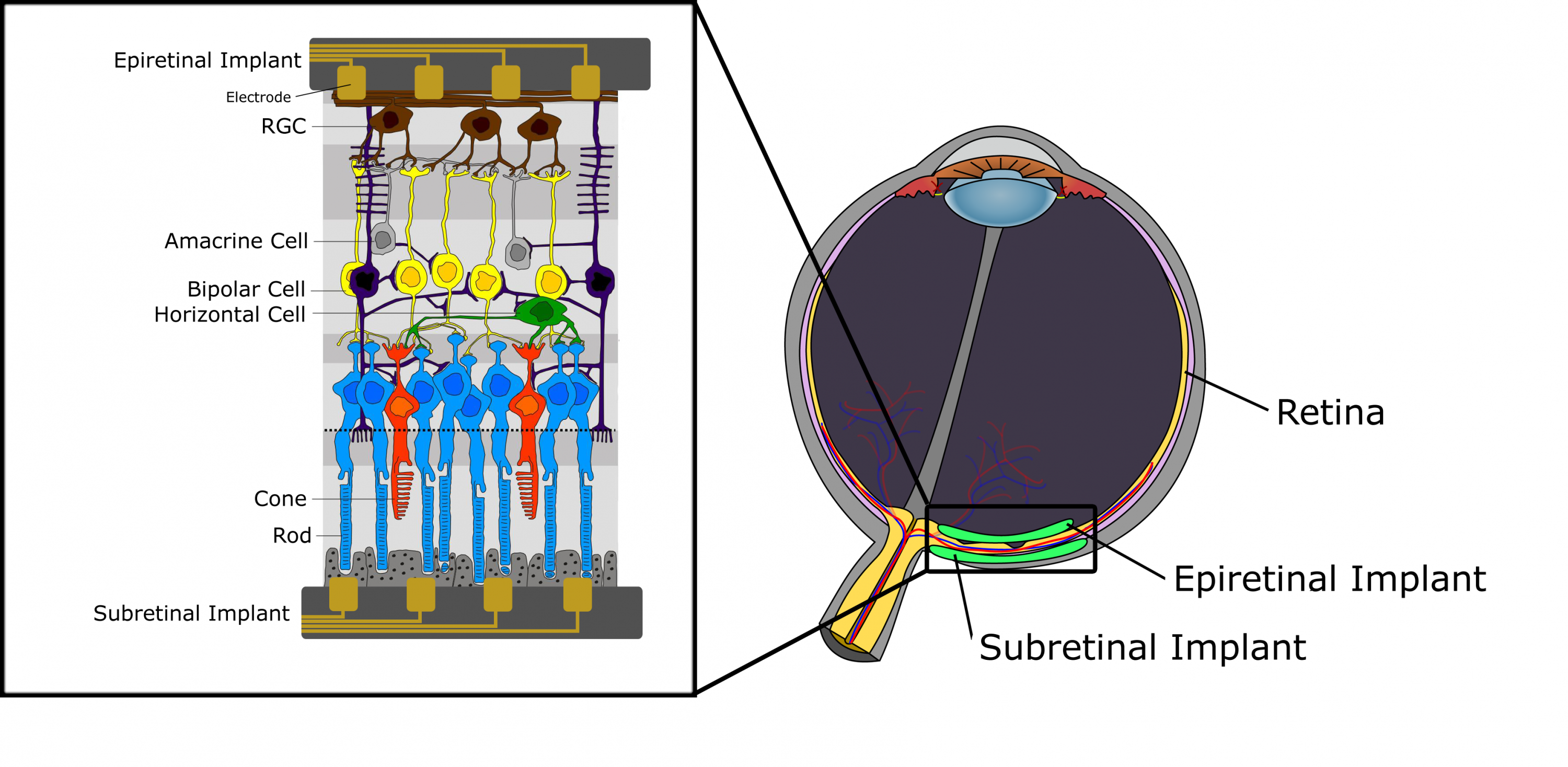

Retinal implants are prosthetic devices that aim to restore some vision to those with vision loss by replacing the role of photoreceptors. They can be epiretinal (on the inner surface of the retina), subretinal (behind the retina) or suprachoroidal (between the choroid and the sclera) and they work by using direct electrical stimulation or by using photodiodes [10].

Ethical concerns with retinal implants

In the article by Slattery [12], it is mentioned that from observing the data from clinical trials it is clear that visual accuracy cannot be guaranteed from the use of the implants, which can lead to misinterpretations that may affect a patient’s day-to-day life. In conclusion, this type of implant needs to be further researched to give people more confidence in its abilities.

Bibliography

[1] B. C. Eapen, D. P. Murphy, and D. X. Cifu, “Neuroprosthetics in amputee and brain injury rehabilitation,” Experimental Neurology, vol. 287, pp. 479–485, Jan. 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.08.004.

[2] D. Infante, “Bionics and Neuroprosthetics: The Future of Functionality with Biomedical Engineering,” News-Medical, Nov. 30, 2023. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Bionics-and-Neuroprosthetics-The-Future-of-Functionality-with-Biomedical-Engineering.aspx (accessed Mar. 09, 2025).

[3] National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, “Cochlear implants,” NIDCD, 2021. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/cochlear-implants (accessed Mar. 10, 2025).

[4] Mayo Clinic, “Cochlear Implants – Mayo Clinic,” Mayoclinic.org, May 10, 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/cochlear-implants/about/pac-20385021 (accessed Mar. 10, 2025).

[5]“Cochlear implant in Singapore – Hearing Specialist & Audiologist in Singapore | D&S Audiology,” Dsaudiology.sg, 2022. https://dsaudiology.sg/implantable-devices/ (accessed Mar. 11, 2025).

[6] “Benefits and Risks of Cochlear Implants,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Feb. 09, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/cochlear-implants/benefits-and-risks-cochlear-implants (accessed Mar. 11, 2025).

[7] S. Byrd, A. G. Shuman, S. Kileny, and P. R. Kileny, “The right not to hear: The ethics of parental refusal of hearing rehabilitation,” The Laryngoscope, vol. 121, no. 8, pp. 1800–1804, Jul. 2011, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21886.

[8] S. Ward, “People can move this bionic leg just by thinking about it,” MIT Technology Review, Jul. 2024. https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/07/01/1094459/bionic-leg-neural-prosthetic/ (accessed Mar. 12, 2025).

[9] Marcello Ienca, G. Valle, and Stanisa Raspopovic, “Clinical trials for implantable neural prostheses: understanding the ethical and technical requirements,” The Lancet Digital Health, Jan. 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2589-7500(24)00222-x.[10]

[10] L. N. Ayton et al., “An update on retinal prostheses,” Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 131, no. 6, pp. 1383–1398, Jun. 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2019.11.029.[12]

[11] “File:Retinal implant eyeimplant small.png – Wikimedia Commons,” Wikimedia.org, Jul. 29, 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Retinal_implant_eyeimplant_small.png (accessed Mar. 12, 2025).

[12] M. Slattery, “The ethical future of bionic vision,” Pursuit, Dec. 05, 2017. https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/the-ethical-future-of-bionic-vision (accessed Mar. 12, 2025).