The Return of an Idea –

As a biologist who seeks to uncover the inner-workings of nature to better understand what makes organisms tick and potentially some day cure the seemingly incurable, the lecture I was most excited for in the UOSM2031 Module was that of the stem cell lecture. It’s among my greatest interests in science – a cell that can become any other, a tool to fit any screw, a piece to fit any puzzle, and I’ve been hotly interested in them ever since my biology lessons in my first year of secondary school. It was there that my biology teacher, Mr. Thomas (I wonder where he is now), stood in front of a class of generally apathetic and sleepless teenagers and spoke about a subset of cells called ESCs – Embryonic Stem Cells – which are pluripotent, unspecialized cells arising in the blastocyst (4-5 day old embryo) of a new organism, and have the miraculous ability to differentiate into whatever cell type the body requires, for the purpose of developing a complete body. These could also be cultured ex vivo in labs.

This was all covered in the lecture on the 3rd of February, but was not particularly new to me; what really piqued my interest that day was remembering an idea I had all those years ago. An idea that I took to the equally sleep-deprived Mr. Thomas after class and asked him, “Sir, what if we made hybridoma stem cells?”

A New Frontier of Immunology –

Now the idea was merely that, an idea. Very little deep thought was put into the logic and science of its functionality or practicality, but it was Albert Einstein who was thought to have said, “Innovation is not the product of logical thought, even though the final product is tied to a logical structure”. You have to start somewhere! Just the week prior we had been given a lecture on a type of cell culturing technology called Hybridomas, cell lines that would continually and rapidly produce monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for the purpose of harvesting the antibodies for treatments, and these cells producing them would ideally never senesce (grow old and stop dividing). The reason for this? They were created from cancer cells. From the fusion of a designated B-lymphocyte immune cell taken from experimental animals and a myeloma (cancerous immune cell), a heterokaryon (cell with multiple nuclei) would be produced capable of unrestricted proliferation and antibody production – key elements of its constituent cells. Practically, it is a useful method of harvesting large amounts of dedicated antibodies towards a specific disease, and as old and low-complexity as it is, being a method originally developed in the 1970s, research is still conducted on it today, simultaneously to assess its viability alongside modern techniques.

Moraes et al., (2021) seek to compare hybridoma and mAb technologies with other emerging approaches, and discuss their benefits and limitations in this research paper.

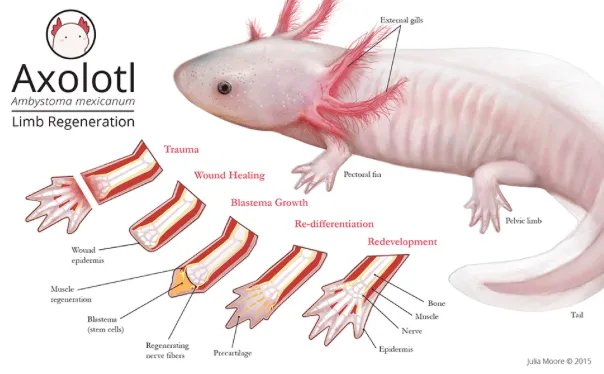

To apply this idea to stem cells, what exactly was my approach? While I have done much research into hybridomas and stem cells over the years to better understand them, there is still much to figure out towards it being a working method, but the general concept is simple: combine a pluripotent stem cell with the endless proliferation of a cancer cell to yield a rapidly multiplying source of stem cells for fast and effective treatment. The challenges and difficulty are obvious concerning the use of cancer and ESCs to try and make a new cell line but I feel the benefits outweigh any costs. Almost like an axolotl is able to do, this may allow for the total repair/replacement of entire limbs, organs and tissue all from within the body itself, fully coinciding with the principle purpose of this academic module, Engineering Replacement Body Parts. It can go even further however; replacing neurons which is a most challenging aspect of medicine could be the key to eliminating neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Dementia, which I have experience with in my family and through my mother’s work in the NHS (always an inspiration of mine). So it is clear to see where my motivation for the idea strives from… but will ethics even allow this research?

The Bane of Scientific Advancement? –

The reason for this whole retrospection of my hybridoma stem cell idea in the first place was because I attended a lecture recently that revisited these concepts, and then I had proceeded to have another lecture that revisited yet another aspect of cutting edge scientific development that holds great relevance in the realm of this discussion, only this one I’m slightly less excited about – the ethics of stem cell research. While I call it my least favourite part of the course, it’s not for lack of importance or interest in its discussion, but that it always seems to be the dampening factor on developing a lot of these ideas. On the 3rd of March, we discussed in lesson the ethical arguments surrounding using stem cells for research, and how in 1990, the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) was set up to establish the guidelines for using them, in response to an enquiry headed by Dame Mary Warnock as to whether scientists should be allowed to freely experiment on the surplus embryos, not only for the reason of harvesting the ESCs from the embryos that would effectively be ‘destroying’ them. They eventually settled on the ‘14-day rule‘, where embryos could only be studied for 14 days at maximum in the lab, or until the ‘primitive streak‘ had appeared on the embryo (a division line of cells).

The main reasoning for this and the discussion as a whole is a whole host of moral/ethical arguments as to whether it is ‘inhumane’ to be treating these embryos like mere lab samples and whether stem cell research is effectively the termination of a potential life. Truth be told, I believe these ethical ‘dilemmas’ often get in the way of true scientific breakthrough for the simple reason that people are afraid of what they don’t understand, and things that seem unnatural or are otherwise unexplored frontiers are often viewed as taboo. I have to give Baroness Warnock some credit however, as she claimed the 14-day limit was more to “allay public anxiety” rather than be based on science, indicating the interest in its study was vital, and this was more to keep society ‘happy’. The embryos studied in question are usually excess embryos from fertility clinics that will get destroyed either way if unused, and to not use them for what is potentially life-saving research at the risk of ‘messing with life’ seems silly, and calls into question a very common argument those that are against commonly use: that an embryo is more valuable than a typical culture of cells. If so, would the life of someone with dementia who could greatly benefit from something like hybridoma stem cells be equal to that of an embryo that may very well never develop beyond a certain point? If morals are the standard, what authority decides a human life is any more valuable than any other animal? Obviously, it is an expansive and sensitive discussion that needs exploration well beyond this brief outline, but I only call it into question because it was the very Mr. Thomas himself – my biology teacher – who said “would people really accept the use of cancer and embryonic stem cells as a treatment if it meant ‘people had to die’ for it to work?” He was being metaphorical for the most part and said it mainly to promote thought, but it did make me think. I understand the hesitancy to destroy something as ‘valuable’ as embryos for science, and if this bothers people, what would they think of combining it with cancer, or even then implanting that in someone’s body? I don’t doubt an entirely new discussion and set of guidelines would arise to take control of this approach as well, and as it almost always about control, that is what bothers me. But perhaps I am sometimes too unsentimental and brazen about the issues – I only want to make the world a better place, and in my mind I see the trial and error using these sensitive resources a ‘necessary evil‘ for the betterment of humanity. These ethics are here for a reason after all, and a society without rules will collapse into anarchy, so perhaps this is a large part of my ‘grand’ idea that I have yet to fully explore; maybe research into the method will yield a better way for me to make it a reality, one that makes everyone happy.

References:

- Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, 2002. Stem Cells and the Future of Regenerative Medicine, Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223690/#:~:text=Embryonic%20stem%20cells%20(ESCs)%20are,all%20three%20embryonic%20tissue%20layers.

- ScienceDirect.com, 2014, Chapter 5 – B Cell Development, Activation and Effector Functions, Editor(s): Tak W. Mak, Mary E. Saunders, Bradley D. Jett, Primer to the Immune Response (Second Edition), Academic Cell, Pages 111-142, ISBN 9780123852458, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385245-8.00005-4

- Moraes JZ, Hamaguchi B, Braggion C, Speciale ER, Cesar FBV, Soares GFDS, Osaki JH, Pereira TM, Aguiar RB. Hybridoma technology: is it still useful? Curr Res Immunol. 2021 Mar 22;2:32-40. doi: 10.1016/j.crimmu.2021.03.002. PMID: 35492397; PMCID: PMC9040095.

- Moore, J. 2015, Axolotl, [Image], Available at: https://medium.com/quarkmagazine/are-axolotl-the-key-to-everlasting-life-b4b35c9649a5

- Le Bras, A. New insights into axolotl brain regeneration. Lab Anim 51, 250 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-022-01063-3, Published 23rd September 2022.

- Pyke, S. 2025, Dame Mary Warnock, [Image], Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01277-5