Prosthetic hands are used to support people that are missing their hands due to a congenital condition, an illness or from an injury. They can help with mobility, strength, and everyday tasks. Some children will wear a prosthetic hand throughout their life whereas other children may never wear one. Prosthetic hands encourage children to use both their hands which improves their brain and motor development. They also help with their appearance and self-confidence.

Development of the prosthetic hand

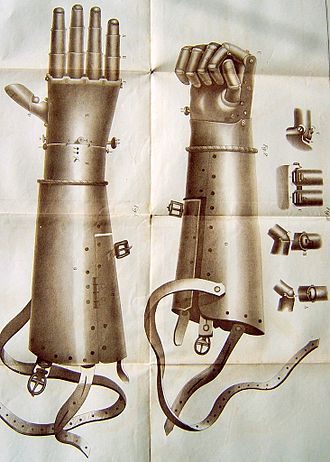

In the late 15th century, France and Switzerland were making artificial hands. These were made from wood, glue, metal, and leather. In the 16th century, Götz Von Berlichingen wore 2 iron prosthetic hands due to losing his right arm from the war. The second hand was able to hold objects. In the 19th century, William Robert Grossmith created a left prosthetic arm from wood and aluminium. In the 20th century, plastic was used for prostheses. Today, prosthetic hands are made from silicone, titanium, aluminium, and plastic.

Cosmetic devices

For children under 18 months an ideal prosthetic hand is a passive prosthetic device which is a cosmetic device. These do not move by themselves; they are made from silicone and are lightweight. The earlier a child starts wearing a hand prosthesis, the more they become accustomed to it. The Greek Series, Infant 2 Hand, L’il E-Z Hand and Lite Touch Biomechanical hands are examples of prosthetic devices that can be used for children.

The Greek Series are suitable from 4 months to 3 years old. They have realistic hand features so they can be used to hold light objects such as small plastic toys.

The Infant 2 Hand can be used from 6-18 months. This hand can be used for pushing and pulling objects as the hand is a cup shape.

The L’il E-Z Hand is suitable from 6-24 months. This hand has a mechanical thumb which helps infants to grasp objects easily.

The Lite Touch Biomechanical hands are recommended from 2-9 years old. This hand has moulded fingers which can voluntarily open and close.

Myoelectric prosthesis for children

Myoelectric prosthetics are suitable for older children, over 10 years old. These use more advance technology and can benefit children as it develops their muscle memory and helps them perform activities that involve 2 hands.

3D printing for prosthesis

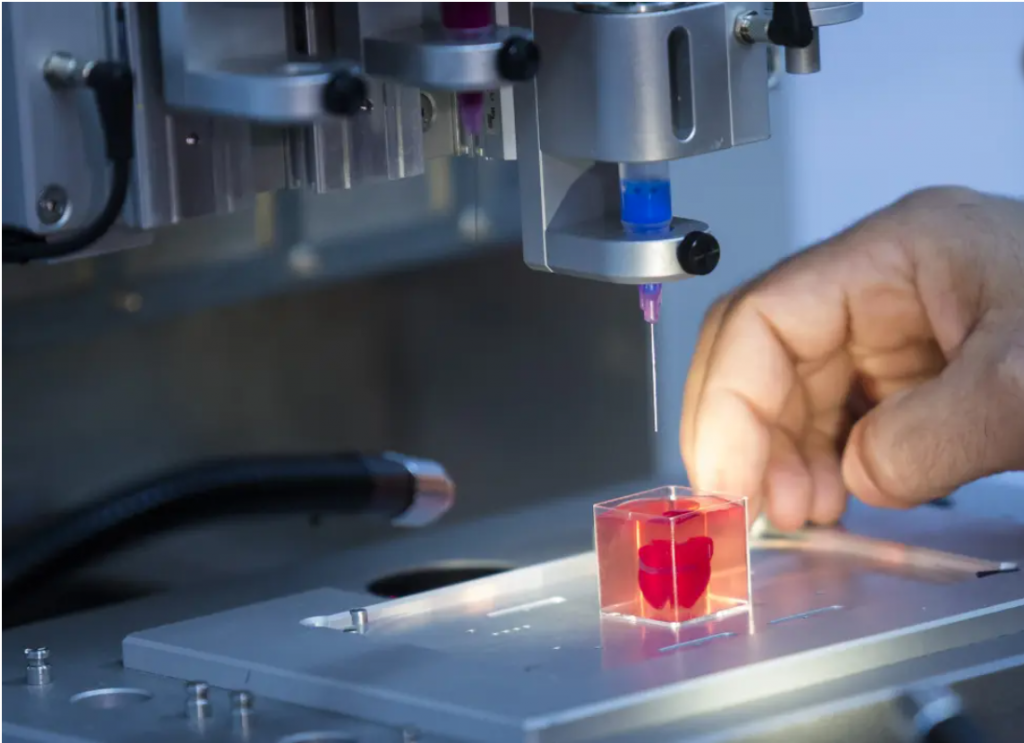

3D-printing technology can make prostheses more affordable for the public. It also reduces the manufacturing time which can take up to 6 weeks. Instead, a prosthetic limb can be created within a day. The aim is to make 3D printing more accessible so people can make their own hands. In 2011, Ivan Owen created the first prosthetic hand using 3D printing. These prostheses are made with plastic, carbon fibre, aluminium or titanium therefore making them lightweight.

Overall, prosthetic hands have developed significantly over the years. They are very important for both children and adults as they can positively impact their lives by developing their everyday skills. There is an amazing foundation called the Douglas Bader Foundation which works with charities in the UK involved in Project Limitless. Project Limitless aims to give all children (that need) a prosthetic arm. Over 300 children have already been provided with one.

Links

https://www.steepergroup.com/prosthetics/upper-limb-prosthetics/hands/trs-paediatric-hands/

Very well written, with an excellent format and images. You’ve included interesting statistics and related it to personal ideas which…

This is a very well written blog, the format is as if you are talking directly to me. The ideas…

Love the Batman GIF :)

This is an excellent, well written blog. The narrative is engaging and easy to follow. It could be improved by…

This is a well-communicated blog. The it is written well with good use of multimedia. It could be improved with…